Chances are, if you have begun reading this article, you care sincerely about making a difference in the world through the work you do in your organization or community. You probably spend considerable time thinking about how to make something happen. You may feel driven to make decisions and do things that produce results. Often referred to as the “urge for efficacy,” this need to accomplish something meaningful is an intrinsic part of who most of us are. Simply put, we want to make an impact.

THE URGE FOR EFFICACY

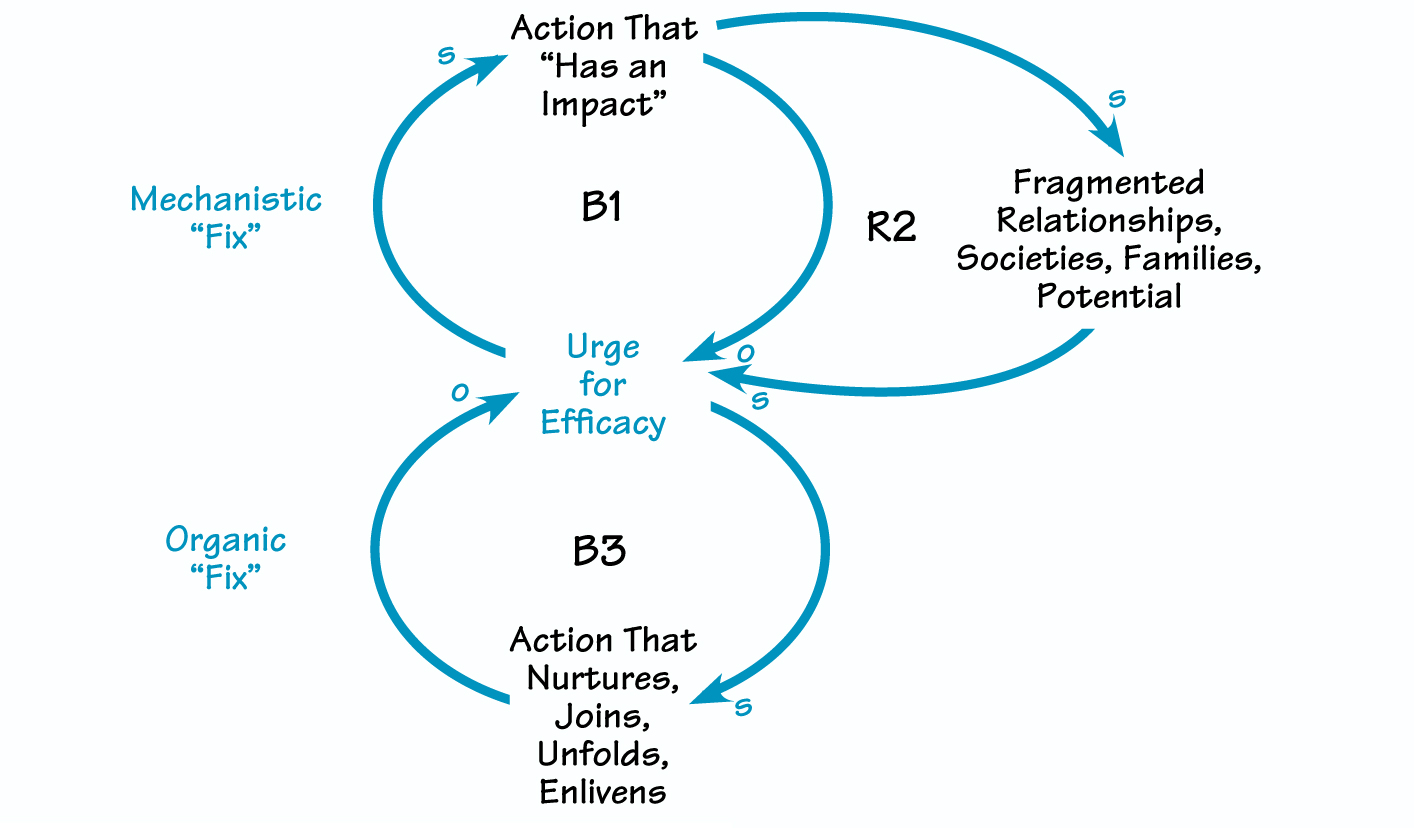

This diagram describes two sets of actions we might take to satisfy our desire for efficacy. Loop B1 represents the mechanistic or “impactful” fix to a problem, in which we push through a solution that involves a radical action. Loop R2 depicts the unintended consequences of this approach, fragmentation, which further exacerbates the original problem, or even leads to new ones. Loop B3 shows how taking actions that are intended to join people together, allowing their ideas and talents to emerge, can help to develop the interconnections necessary for organizational success.

How often, though, have we found ourselves in situations where our best efforts have fallen short of producing the benefits we intended and so deeply desired? Perhaps we have experienced success once, but for some unexplained reason we have been unable to reproduce or sustain the results. More confounding still are those times when, rather than improving performance, creating new knowledge, or adding value, we have found that our actions have had an opposite effect. In these cases, the harder we have tried to push ahead, the more resistance we have encountered.

Why do negative consequences often occur when we attempt to have an impact? For one thing, when we successfully execute actions that are specifically designed to radically alter current work processes and outputs, we generally break apart existing structures (see “The Urge for Efficacy”). Sometimes doing so is necessary, as breaking up and clearing away the old is truly the most effective way to create space for the new. But other times, the result can be fragmentation of a sort that isn’t immediately apparent. The sudden shift to a new “order” can shatter many things people previously counted on to be solid, including relationships, the value systems upon which decisions are based, and the motivations of others. Trust, quite literally, is shaken. People retreat into themselves or in small, tightly knit groups to try to sort out what has just happened and to reestablish their own center. This process can lead to a compartmentalization of ideas and energy within the system, often at a time when the health of the system is most dependent on maintaining and growing its interconnections.

In this article, we will explore the nature of these unexpected consequences and how they might occur, despite our good intentions. We will examine how the work cultures we have created, and even the language we use to describe the act of making a difference, may be partly responsible for unhappy or unsustainable results. We will explore a model that suggests different language choices, as well as a less mechanistic and more organic approach to satisfying our urge for efficacy in our organizations, our communities, and the world. And, we will examine a recent case study in which many of the ideas presented here continue to be tested.

Clues in the Language

“Language exerts hidden power, like a moon on the tides.”

—Rita Mae Brown, Starting From Scratch, 1988

Over the years, I have been fortunate to work with leaders and teams in extraordinary organizations. My own passion for issues related to health, education, and overall quality of life has meant that most of my colleagues and clients have been affiliated with hospitals, educational institutions, the public sector, or government service. As I often find myself working as a strategic learning partner and coach with organizations that are experiencing significant change, the initial conversations quickly and urgently turn to the subject of “what are we going to do?” I have noticed similarities in the language people in organizations use to describe their concerns, questions, and quest to “do something.” Here are some examples of commonly used expressions:

“We’re going to have to wrestle that one to the ground.”

“They’d better be prepared to go to the mat.”

“We can’t afford another idea that bombs.”

“This should break down the barriers to our success.”

“We’ll just keep grinding away at it.”

“Our approach must hit the target.”

“Whatever we do, it’s got to have an impact.”

These phrases all have one thing in common: They employ physical or mechanical metaphors that involve something hitting against or breaking up something else.

My growing curiosity has caused me to listen more closely to the nature of the language people use in organizations to describe their problems and challenges. As I have grown more aware, I have noticed that some individuals and teams, particularly those who strive to carefully consider the nature of any crisis prior to reacting, tend to use a different type of metaphor. Here are some examples of these phrases:

“How can we nurture an environment that supports excellence?”

“Is it possible to go with the flow without being swept away?” “What pathways will take us there?” “Is this part of a larger cycle?” “What can we do to grow these ideas?” “Can we take actions that will create a ripple effect?” “Are we really understanding the nature of the system that created this dilemma?” “What are the healthiest and most sustainable solutions?”

Does the language we use to describe our activity say something about the culture of our workplaces and the methodologies we employ to make meaning?

There are two interesting characteristics of these expressions. First, they are all in the form of questions. Second, they all use natural or ecological images to describe an action or state of being. As I have continued to listen for these language differences, however, I have noticed that the more organic, questioning metaphors are not the norm.

I began to seriously wonder: Does the language we use to describe our activity say something about the culture of our workplaces and the methodologies we employ to make meaning? And, as I heard story after story about change initiatives and performance improvement programs failing, I further wondered if a mechanistic mindset, and, subsequently, approaches to our work, might somehow be connected to producing results that are either unsatisfying or unsustainable (see “Mechanistic vs. Organic Fixes”).

MECHANISTIC VS. ORGANIC FIXES

Characteristics of Mechanistic “Fixes”

- Suggest that problems are inanimate

- Focus on actions that hit against or smash something apart

- Strive to break things (or problems) into pieces

- Want to “have an impact”

- Compartmentalize learning

- Can result in fragmentation

Characteristics of Organic “Fixes”

- Suggest that problems are alive

- Focus on actions that soften enliven, nurture, and grow

- Strive to find or maintain wholeness

- Want to join forces

- Share learning

- Can result in interconnection

Take the word “impact,” for example. Whether used traditionally as a noun (, “We need to make an impact on our customers”) or perhaps more questionably as a verb (, “How will this impact our bottom line?”), this word describes something hitting against something else. Some of the synonyms for “impact,” found in the Synonym Finder (J. I. Rodale, 1978), include “collision,” “crash,” “clash,” “striking,” “bump,” “slam,” “bang,” “knock,” “thump,” “whack,” “thwack,” “punch,” “smack,” and “smash.”

It then occurred to me that an interesting exercise would be to substitute some of these synonyms for the word “impact” in the common and popular phrases I have heard in organizations. Here are some of the more darkly humorous results:

“We need a growth plan that will slam our customer base.”

“This new policy will surely whack the morale of our employees.”

“Our new process improvement program is designed specifically to smash against the quality of our services.”

“Whatever we decide must collide with our community.”

Interestingly, this is also the language that is often used to describe military or war efforts. One example is an article titled “From the Front,” featured in the Albuquerque Journal on March 9, 2003. Writing from a military camp in Kuwait, journalist Miguel Navrot describes the attributes of the redesigned Patriot missile:

“This time, the Patriot is intended to slam directly into targets, destroying it in the supersonic collision.”

While most people do not consciously think about their well-intended solutions as actions that are either based on a military model or designed to smash, crash, and dash something to pieces, one must wonder if there are unintended consequences to this way of talking and thinking about problems and opportunities. Is there not, for example, a natural fragmentation that occurs when we implement actions that constantly hit against ideas, values, work processes, and people? And does this fragmentation support our efforts in the long run, when it causes people to feel disconnected, relationships to shatter, and innovation to become compartmentalized or even disintegrate?

Undeniably there are times when the most effective and necessary actions are those that do, indeed, break something apart, but have we overused these tactics in our quest for efficacy? And, if so, what might constitute the characteristics of a balanced approach?

Looking for an Oasis

Because metaphors paint a verbal picture of ideas, I wondered what would happen if people were asked to draw pictures to symbolize characteristics of different kinds of organizations. Would mechanistic or organic themes appear in their images? To begin exploring this question, I took advantage of three opportunities. The first was an invitation I had received to deliver the closing keynote address to the Public Service Commission of Canada’s annual Emerging Issues Forum for Leaders. The second was the chance to work with members of the Research Association of Medical and Biological Organizations (RAMBO), a diverse group of scientists in New Mexico that gathers regularly to explore scientific questions of mutual interest. The third was an invitation to speak at the 2001 Gossamer Ridge Institute, a think tank of teachers and administrators, mostly from public schools.

At the Canadian conference, I distributed drawing paper, along with markers and crayons in many colors, to all of the participants. I then asked them to create two images: one symbolic of the characteristics and attributes of a typical organization, and the second of the traits of an ideal organization. With the RAMBO group, I asked them to draw a traditional organization of which they had once been a part, and then to draw the RAMBO organization. I asked the educators to draw representations of the typical school and the ideal school.

With each of the three groups, the results were astoundingly similar. Drawings of the “typical” organizations included boxes, squares, and lots of right angles, mostly in black and white or monotone colors. Many drawings depicted rows of people who all looked the same, often captured in contained and compartmentalized cubes. Several incorporated mazes. In almost all cases, the blocky, unifying principles of these pictures were immediately apparent. When asked to describe the meaning of their drawings, people used words such as “constrained,” “programmed,” “stifling,” “demanding,” “demoralizing,” and “dead.”

Drawings of the “ideal” organization showed equally amazing similarities. Brightly colored images of overlapping circles, spirals, prisms, and other free-form designs emerged, with the unifying forces more felt than immediately seen. Depictions of natural landscapes were by far the most common themes: Trees, complete with root systems, were laden with fruit hanging on their branches and birds roosting in their nests. Creatures that looked like amoebas floated in a bright blue sea. Flowers bloomed in the midst of a desert oasis. Purple mountains soared above lush, green valleys and flowing rivers. When asked to describe the symbolism of these drawings, the creators used words such as “flowing,” “creative,” “diverse,” “renewing,” “energizing,” and “alive.” The visual metaphors of the desired organizations, along with the verbal interpretations, indicated a desire for a more organic model than currently existed.

A “Live” Issue

As I mentioned earlier, there are some individuals, teams, and organizations that have consciously chosen to slow down and attempt to understand the nature of the problems or opportunities they are facing, rather than charging full ahead with solutions. The language they tend to articulate reflects a way of thinking that is based on an organic model or world view, rather than a mechanistic one. The use of words such as “nurture,” “create,” and “grow” suggests that the problems and issues are alive and must be treated as such. In fact, this language suggests that the very solutions we employ must themselves be alive. Furthermore, we must understand that the processes we use to choose and implement solutions will ultimately influence the results.

If we choose to think of our opportunities and problems as being alive, how might we change the ways in which we go about planning and taking action? I recently took the opportunity to explore this and other questions about the “urge for efficacy” with Tres Schnell, who serves as the chief of the Injury Prevention and Emergency Medical Services Bureau for the New Mexico Department of Health.

In the aftermath of 9-11 and in defense against possible bioterrorism threats, state health departments throughout the U. S. have been charged with creating and implementing a plan to vaccinate physicians and others who would potentially serve as first responders against smallpox. Over the past few months, New Mexico Public Health Division personnel have devoted much time to developing a thoughtful plan to comply with this request. Based on the principle of “first, do no harm,” the division created a phased approach that would begin with identifying healthcare workers who would likely be the first ones to deal with a patient with smallpox, and then carefully screening to identify and remove from the vaccination pool anyone with risk factors that could lead to adverse effects. The inoculation program would then move forward with its first phase of vaccinating a small group of these primary responders, all of whom understood the potential risks and had volunteered for the program. Over time, the approach would be to carefully and methodically extend the vaccination initiative to other first responders in communities throughout the state, with constant monitoring of any adverse effects or signs that adjustments to the strategy should be made. The plan was implemented during the first week of March, with a handful of key personnel receiving the vaccine.

However, as fears of pending war with Iraq began to escalate, the call came to step up the program and to take actions that would have greater “impact” on the goal of vaccinating more people in a shorter period of time. The Department of Health was suddenly faced with a new sense of urgency to get the job done. I asked Tres about her views on the request to move faster, the possible unintended consequences of doing so, and an approach that could serve to mitigate or avoid those consequences.

When people feel that they are not being heard, they tend to compartmentalize themselves according to their alliances. Blaming often occurs, and then conscientious objection becomes passive, and then active, resistance.

Tres began by relaying the story of the planning process. “As we planned our approach in New Mexico, we did so knowing that opinions about the whole process were diverse,” she explained. “There are many health professionals in this country who do not feel that vaccinating people against smallpox is the right thing to do, given the potential risks of the vaccine itself, and the fact that doing so will divert resources away from other critical public health initiatives. Knowing this, we listened to all views, carefully weighed the risks, and developed a plan that held sacred the charge to ‘first, do no harm.’We were well on our way, through building a strong public health infrastructure and trust in a thoughtful process, to implementing a smallpox vaccination strategy in New Mexico. What we must do now is to respond to this new sense of urgency without creating a situation that divides us internally and diminishes the organic approach we believe is critical to the safety and effectiveness of this initiative.”

Throughout it all, Tres said, “We have the goal of remaining whole, because it is through wholeness that we can be most effective. The danger is that when people feel that they are not being heard, they tend to compartmentalize themselves according to their alliances. Blaming often occurs, and then conscientious objection becomes passive, and then active, resistance. We begin to rationalize that the people who don’t think like we do must be ‘bad.’ So, we cannot allow ourselves to be seduced into a defensive posture that builds those barriers to open, honest information sharing and dialogue. We cannot afford to fragment our relationships as we address the smallpox issue.”

In her role as leader of Emergency Medical Services, Tres insists that decisions on how to proceed cannot be made until the health professionals and their concerns have been heard, no matter how diverse or controversial the ideas. “Our diversity is our true strength,” she says. “This will help people to remain united, not harming each other in ways that will hurt our ability to be effective in the long run. Maintaining and nurturing relationships with one another is more critical now than ever.”

LANGUAGE/ACTION ASSESSMENT

- What are some of my favorite analogies and metaphors that I use to talk about my work issues and opportunities?

- Would I and those around me characterize my favorite phrases as mechanistic or organic?

- Do I believe that my metaphors communicate my true intentions and values?

- As I think about the last year and the challenges and opportunities I have faced, what actions did I advocate and/or take that were specifically intended to “have an impact?” What were the short- and long-term results? Did any fragmentation occur?

- What actions did I advocate and/or take that served to soften, nurture, join, unfold, enliven, or emerge? What were the short and long-term results? Did something desirable grow or connect as a result?

- What words or metaphors might I add to my vocabulary to create a balance between mechanistic and organic language?

- What actions might I advocate or take that will help to create a balanced approach to achieving my goals?

- What conscious choices will I make today about my thoughts, language, and actions?

Asked about the messages she is sending to her colleagues, Tres responded, “We need to consciously choose our language — our mantras, if you will — selecting those that maintain and communicate our core principles and values. We must prioritize around our commonalities, not our differences. The threat we are currently facing is the added sense of urgency. If we can respond well to this one, we will learn and respond even better the next time.”

The messages are clear: that the language used and the methods employed must serve to join ideas, perspectives, and people if this very serious issue is to have a positive outcome. In the case of smallpox vaccination plans in New Mexico, the health professionals are finding strength and connectivity in their shared passion for protecting the public’s health. It is a critical time for leaders to model the willingness to listen deeply to differing viewpoints and honor one another’s professionalism. This willingness, coupled with strong relationships that have grown from working together in the past to address public health issues, is enabling the team to move forward more quickly with the plan while at the same time continually monitoring concerns and issues as they arise.

Improving Our Awareness

“If language is not correct, then what is said is not what is meant; if what is said is not what is meant, then what must be done remains undone; if this remains undone, morals and art will deteriorate; if justice goes astray, the people will stand about in helpless confusion. Hence there must be no arbitrariness in what is said. This matters above everything.”

—Confucius

Do we consciously choose our metaphors and our methodologies for taking action, or have our responses and approaches somehow become automatic? And if the latter is true, how can we make a conscious attempt to become more aware of our own language and the influence that our words may have on the nature of the actions that we and those around us take?

The “Language/Action Assessment” on p. 5 is intended to help us to explore our own favored metaphors and the kinds of actions they describe. Take a moment to consider the questions it includes. As you think about your responses, reflect on how experimenting with other language choices might possibly lead to solutions and actions that are more organic and alive than other possibilities. Engaging in this exercise can also be helpful when done as a team activity, especially as part of a strategic or operational planning process.

In answering these questions, we become more aware of our past tendencies. As we more clearly understand our past, we are better able to make thoughtful choices about our future language usage and subsequent actions. In this way, the exercise can help us to achieve true, lasting efficacy.

Choosing the Words We Live By

Whether we are addressing global issues such as the threat of bioterrorism or concerns more specific to our organizations and local communities, thoughtfully and consciously choosing our words and deeds is surely the wisest course of action. The desire to make a difference may well be our birthright. But how we go about attempting to make that difference can affect the quality and sustainability of the outcomes and of our lives. The words of an anonymous philosopher serve to remind us of how what we think can shape who we are:

Watch your thoughts, they become your words.

Watch your words, they become your actions.

Watch your actions, they become your habits.

Watch your habits, they become your character.

Watch your character, it becomes your destiny.

Being human means that we are endowed with the wondrous capacity to consciously choose our words and actions. May we increasingly exercise our ability to do so with clarity, compassion, and an understanding that what we say and do will create our future.

NEXT STEPS

- Use the Language/Action Assessment tool as part of the start-up process for a new team or to help a team that has reached an impasse in its work assignment. People can either do the assessment independently and discuss the insights that it provokes or complete it as a group, replacing the words “I” and “my” with “we” and “our.”

- Develop a list of words, phrases, or metaphors that reflect the intent of the messages you consciously wish to send to external customers and to each other. The purpose of this exercise is to raise everyone’s awareness of the power of words and language to influence relationships, processes, and outcomes.

- Use markers and paper to depict how your group, department, or organization currently operates. Then draw a picture representing how you wish it could function. Compare and contrast your “works of art.” How could you bridge the gap between your current reality and your desired future? What language would you use to communicate your picture of the ideal state?

- Discuss how you would approach your tasks and assignments differently if you considered them to be “alive” rather than inanimate. How might you nurture ideas, feed creativity, plant seeds of change, and cultivate relationships so that you will harvest the results you most deeply desire?

Carolyn J. C. Thompson has devoted more than 20 years to helping organizations create vision driven and values-centered workplaces that are able to ask and address hard questions through engaging the power of the human spirit. She teaches, writes, and consults both in the U. S. and abroad on applying systems thinking and complexity principles to organizational issues. Carolyn resides in Albuquerque, New Mexico.