Over the past two years, organizational learning has grown from a buzzword into an integral feature of the Singapore Police Force. It has been operationalized to some degree, both at the strategic level and in the day-to-day work of officers. Many feel that the concept is useful as a tool and as a common language for bringing about profound change. Our leaders have made a conscious effort to, “walk the talk,” encouraging experimentation and innovation in making organizational learning real in daily work processes.

Indeed, it is by the leadership team’s engendering a safe environment for practice that officers can be open in their views and honest in their sharing with one another. This support for the effort has signaled to the masses that the movement is not a passing fad, but indeed relevant to our organization. The awareness of the concepts and the power of the tools of organizational learning have drastically shifted SPF’s orientation and the way we think, behave, and work together. This change, in turn, has improved our ability to protect and serve the Singaporean people.

Team Learning Prototype

The SPF is a 12,700-person force. Line commanders are accountable for the entire gamut of policing functions. They are supported by staff departments in specific areas, such as operations, investigation, intelligence, logistics, and so on. These staff departments are headed by directors who, together with the commissioner and the deputy commissioner, form the top-level management of the SPF.

In 1992, then-Commissioner Tee Tua Ba introduced the Commissioner of Police Directorate Forum (CPDF), which were regular meetings attended by all staff directors. The sessions were intended to be a place for management to explore cutting-edge ideas and to brainstorm innovative solutions. One of the more interesting “ground rules” of CPDF was that comments made during meetings would be non-attributable, so that participants could speak freely. This aspect of CPDF was relatively short-lived; nevertheless, it served as an important experiment in team learning.

In 1996, the SPF’s commander sand directors, and certain officers identified as key change agents, participated in a five-day organizational learning course. Over time, more than 200 officers have been trained in the practices of organizational learning.

Because its “charter” was open-ended compared to that of other departmental forums, CPDF proved to be a good practice field for trying out facilitated meetings, dialogue, and skillful conversation. The forum was expanded to involve the entire leadership team, including the line commanders. Younger officers who have been trained in organizational learning concepts and tools were brought in to help facilitate discussions. Today, the 40-member group meets about once every two weeks. The forum has a pool of about 15 facilitators, who are staff officers based largely at police headquarters.

The leadership team meets “organizational learning – style” in a place away from headquarters. The physical layout is essentially a circle of chairs, with flip charts, an overhead projector, and, more recently, a laptop computer linked to a projector at the front.

There is no “chairman’s” seat. In fact, senior officers always make a point of sitting scattered throughout the circle. Issues are reframed into “discussion questions,” with care taken to avoid leading the group into polarized yes/no situations. The session takes the form of either breakout groups or a large-group discussion, with a facilitator and a recorder.

Over time, the agenda for the CPDF has moved away from hard-core operational issues to softer, open-ended but nonetheless equally important ones, such as the nature of leadership in a police organization, the efficacy of internal communication, and the sense of how the force as a whole is responding to certain initiatives or decisions by headquarters. Such issues formerly would not have merited discussion. At the end of each session, the secretariat of CPDF circulates a short summary of the discussion and observations on how well the leadership team performed during the meeting in terms of collective thinking and team learning. This document serves as an additional source of reflection and feedback to the members on the development of their interpersonal skills.

Cascading OL

Over the last two years, the SPF leadership group has achieved two significant milestones. The first is the creation of the SPF Shared Vision. The second is the collective effort to create a plan for realizing that vision. The initial step in the implementation was to introduce ground officers to organizational learning concepts and tools. Through that process, the officers bought into the SPF Vision and also co-created their unit visions, using organizational learning tools such as the Vision Deployment Matrix™, Inquiry and Advocacy, and the Left hand Column. To augment this effort, we also incorporated organizational learning into our training program for new recruits.

SPF then took pains to implement these concepts in a holistic manner and to weave them seamlessly into the organization’s architecture. Other key meetings became more, “OL” in process. Learning centers, with multimedia learning aids and resources on organizational learning, were set up in various police establishments to encourage personal mastery. The SPF also sets aside time and resources to allow units to conduct regular retreats, where group members share perspectives through suitable activities. The SPF Discussion Group, an electronic forum on our intranet, has become a medium for dialogue about many current issues, thus spurring openness laterally and vertically in the organization. Overall, the flow of information has become faster and more transparent, which is critical for pushing learning forward.

We have also integrated organizational learning into our scenario planning and business process reengineering efforts to bring about collective thinking among stakeholders and encourage the examination of mental models and unintended consequences. We institutionalized After Action Reviews, adapted from the U. S. Army, into our work processes to engender team learning and continuous improvement. In addition, the way we handle mistakes now is oriented toward learning and improving, not to assigning blame. Of course, officers would still be taken to task if they committed serious offenses. We make a point of sharing best practices across the SPF, so that others can benefit from them. All of these changes have been underscored by many examples of bottom-up initiatives that displayed the acceptance of organizational learning within the police force.

Initial Successes

What results have we found from this change in “business as usual”? We have noticed higher energy in the workplace and an improvement in relationships among the staff, with greater clarity and honesty in communication, especially regarding “undiscussables.” The yearning for collective thinking has also strengthened our ability to challenge the status quo and to create higher quality plans. This in turn hassled the staff to show greater initiative and ownership over issues. The appetite to learn, to acquire skills and knowledge, and to seek wisdom has grown, as manifested in officers’ sharing of articles, experiences, and mistakes with one another. Trained to take a more holistic view of the organization and their role in it and to think, “out of the box,” members of the SP Fare increasingly looking at issues from a broader, national perspective rather than from their own narrow silos.

What about the average Singaporeans “on the street”? Would they notice a difference in how the SPF is run? Some anecdotal evidence indicates that the Force has been more responsive to the needs of the public than before. We have also won people over with our sincerity about learning from our imperfections. This was shown through an incident that received a lot of publicity in which some officers parked their police vehicle in a handicapped lot while responding to an urgent situation. The SPF issued an apology for the officers’ insensitivity. We’ve also become more flexible in adapting our operating strategies to suit a particular situation and to solve individual cases. Finally, some of our reservists have noticed a greater openness across SPF as compared to the past.

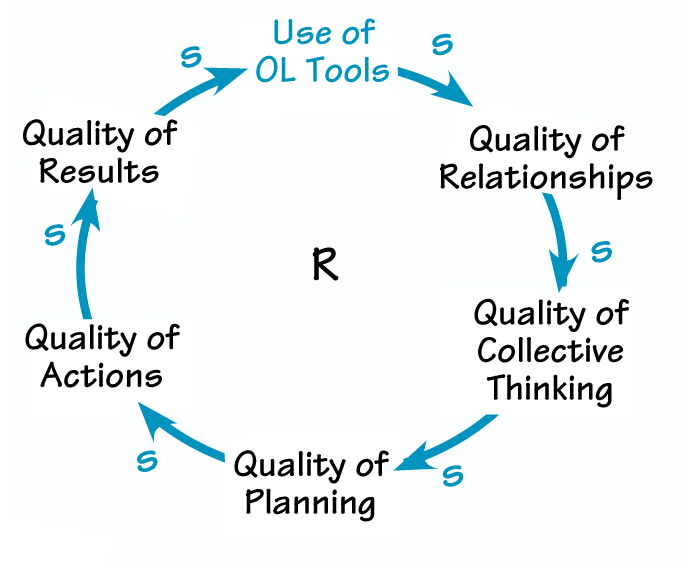

These phenomena are a manifestation of our philosophy of organizational learning, which is summed up in the diagram “Cycle of Quality.” We believe that the practices of organizational learning lead to higher quality relationships, which in turn bring about higher quality collective thinking. The garnering of collective wisdom leads to better plans, and with better implementation of the plans, we achieve superior results. This success reinforces the belief that “OL works for us,” and thus further enhances the quality of relationships.

Beyond SPF

CYCLE OF QUALITY

However, no single agency is formally coordinating this effort now, and different organizations in the public service have responded to organizational learning with varying degree of acceptance and enthusiasm. Still, our deputy prime minister has stated that as a country we must become “a learning organization.” We thus see the Public Service Division (under the Prime Minister’s Office) gradually taking a greater role in driving the changes and the adoption of organizational learning concepts in the public service domain, including schools and quasi-governmental organizations.