In the popular science fiction TV series Star Trek, the Vulcans, an extraterrestrial species, possess a unique characteristic: They can wordlessly share thoughts, experiences, memories, and knowledge with others through a technique called a “mind meld.” Unfortunately, we real-life humans don’t share this trait. Not only do we struggle to communicate our thinking to others, we often act without being aware of the assumptions that shape our understanding of the world.

Mental models, the pictures or maps we have in our minds that we employ when interpreting, judging, and deciding, are one of the five disciplines of a learning culture (the others are systems thinking, shared vision, personal mastery, and team learning). Our mental models control our actions, and yet we tend to be unaware of the specifics embedded within them. Most of us have not been trained in reflective learning to test our own thinking and understand its impact on ourselves and others.

TEAM TIP

The next time your team needs to come to a shared understanding of a complex issue, create a continuum of possible positions. Doing so will prompt deep conversation and ultimately coordinated action.

As a result, when confronted by opinions that conflict with our own, we generally defend our thinking or feign interest in someone else’s mindset rather than submit to the subtle and deep work of testing our own mental models. We rely on and are often rewarded for the repertoire of responses we have developed to familiar stimuli in our environment. We look for the right answer to solve the problem or question, based on our past experience. If well practiced, we can be on automatic pilot and push our way through a workweek of data, expectations, and requests from others without examining or questioning our underlying assumptions.

The situation gets messier the more people are involved. Groups hold mental models about their relationships and actions. As we join a team, organization, club, or society, we may have a mentor who guides us through the norms for that group, for example, the proper way to assert oneself and to disagree, the distribution of power and status, the type of data that the team values, the role of money, ground rules, etc. Often the subtleties and undiscussables are left for us to discover as we inadvertently bump into them in the course of our work. In the process of trying to dive into the thinking behind people’s actions, we may end up putting them on the defensive, whether we intend to or not.

Add one more layer of complexity by focusing on a group with fiduciary responsibility for an organization in perpetuity. A board of directors or trustees must work together to govern an organization in all its complexity and ensure the public that best decisions are being made on behalf of all stakeholders. Many boards meet in person four to six times a year, with committee meetings in between, either in person or through conference calls. Members begin to build familiarity by observing each other’s behaviors (he talks too much, she asks good questions, she demands data, he rushes to decide, etc.), but they seldom get to know each others’ mental models about the institution, governing, the role of senior leadership, group decision making, and so on. To be an effective board, members need to know a lot about how other members think. And they need to carve out time for defining their prevailing governance model.

Building shared mental models while taking advantage of the diversity of thinking in a group requires the disciplined deployment of time and talent. If we were better at reflective learning, we could draw out each person’s key assumptions and beliefs. In the absence of such facility, one method to promote deep conversation, model building, and coordinated action is to display a continuum of possible models. There are numerous ways to organize options about a given situation, and each has a distinct impact on the members, organization, and future. Start by doing the research and designing a continuum of positions on an issue. It’s not about having the perfect representation or right answers; the goal is to stimulate the group’s thinking so members can arrive at a shared mental model about a critical issue. Here’s an example of a group that took this approach.

A Green Story

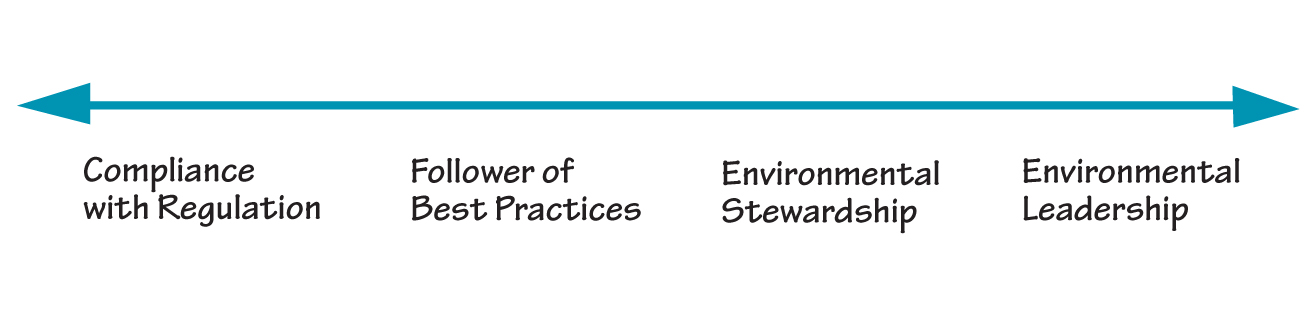

Senior leaders in a public utility client felt it important to engage the board in an exploration of the company’s commitment to being green. Green strategy isn’t free; it requires an investment, depending on the chosen course of action. I partnered with the newly appointed leader of the environmental science department to craft a continuum of positions to provoke a broad and deep conversation about which position the board could support (see “Continuum of Positions”).

The first two positions – Compliance with Regulation and Follower of Best Practices – are reactive and depend on others in the industry to do the initial experimentation and learning. Both avoid risky investment because others prove the practice. The board members clearly understood the distinction between the two approaches. It was the discussion of Environmental Stewardship versus Environmental Leadership that enlivened the executives and directors.

After a rich dialogue, they decided that, in their model, Stewardship would involve activities within their organization. It would include a bias toward innovation as long as there was some evidence that the proposed initiative would be effective and provide an adequate ROI. Leadership would involve researching and experimenting with existing and new technologies, perhaps inventing a new process or technology, and teaching others in the industry the lessons learned along the way. Clearly Leadership is the most expensive and intensive choice.

CONTINUUM OF POSITIONS

One method to promote deep conversation, model building, and coordinated action is to do the research and design a continuum of positions on an issue. It’s not about having the perfect representation or right answers; the goal is to stimulate the group’s thinking so members can arrive at a shared mental model about a critical issue. A public utility used this continuum to provoke conversation about its green strategy.

As the executives and directors became comfortable with the emerging model, they realized it wasn’t necessary to declare only one position. The director suggested that, over the next five years, in some areas, they will fall into compliance; in others, they will seek out best practices to implement; and in still others they will commit to innovate for the benefit of the communities they serve. When asked if this approach represents a cop out, the leaders were adamant that their aspiration is Environmental Leadership but practicality required discernment of what they could afford to execute in the near future.

The team couldn’t be too attached to the model we had crafted from our research because throughout the process, we redefined and rearranged the continuum. Our satisfaction came from the quality of thinking and conversation and the commitment generated by the joint model-building process. The model served the purpose of helping a group of people make hard choices.

A Continuum of Evolving Governance

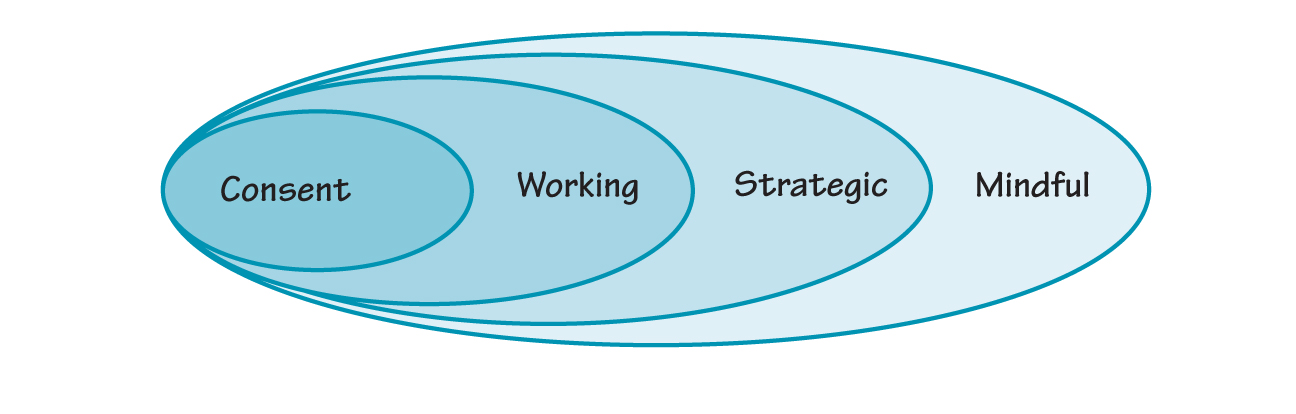

Sometimes the shared model is not about choosing but about becoming aware of a developmental path. A continuum of governance models for boards of directors or trustees that I developed with my colleague Martha Summerville (see “A Continuum of Governance Models”). It allows board members to clarify their personal model of “good governance” and engage in a dialogue about what type of board the group believes it currently is and aspires to be.

Let me briefly describe the differences among the options:

Consent Board. A consent board perceives that it has a few direct responsibilities: financial oversight and audit; the hiring, firing, and compensation of corporate officers; ethical corporate behavior; and understanding of customer interactions. Senior leaders are responsible for operations and strategy, which the board reviews. This board takes direction from senior leaders for setting the agenda for board meetings and for selecting new board members. The executive committee makes most decisions that arise that do not require a specific number of affirmative votes in the bylaws. Most items that come before the board for a vote have already been vetted by the chair of the board and the CEO. Votes in board meetings are usually unanimous, so interactions are cordial. Any serious conversations are taken “off line.”

Some dangers of remaining a consent board are unanticipated events in the organization that reflect poorly on the board, unethical behaviors among the leadership team, and boredom on the part of board members. Recruiting strong board members can be difficult unless the board changes its mind and culture.

CONTINUUM OF GOVERNANCE MODELS

Sometimes the shared model is not about choosing strategies but about becoming aware of a developmental path. This continuum of governance models for boards of directors or trustees allows board members to clarify their personal views of “good governance” and engage in a dialogue about what type of board the group believes it currently is and aspires to be.

Working Board. To increase their effectiveness or in response to pressure from key stakeholders or the media, consent boards generally find that they need to learn about the organization from the inside out rather than remain superficially aware of operations. Boards often make this shift after a scandal or crisis. Their focus becomes critical measurable outcomes. A working board usually has several committees, for example, Quality & Safety, Finance & Audit, Regulatory, Culture & Employee Engagement, Governance & Leadership. Each committee works with a senior leader as a liaison to consider relevant data and assess pending strategic decisions. Early in the evolution from consent to working board these committees may dive too deeply and get too involved in operations. Senior leaders and board members need to establish clear boundaries and responsibilities to maintain a positive working relationship.

A working board sets its own agenda, including its learning agenda, with input from senior leaders. It regularly evaluates its own performance to give the public confidence in its oversight on behalf of key stakeholders. Face-to-face board meetings have committee time and plenary time. Because working boards have more responsibilities than consent boards, meetings tend to be longer, with virtual committee meetings in between formal meetings and an annual board retreat. Potential directors need to be aware of the amount of commitment (time, talent, and money) required.

The dangers of remaining a working board include a stagnant organizational identity, weakened senior leadership, and burnout of board members.

Strategic Board. At some point in the evolution of their relationship with senior leaders and of their thinking, the board makes the shift to being a strategic board. Often the shift is prompted when senior leaders ask the board to elevate the level of its deliberations, and board members affirm they have deep confidence in senior leaders to carry on the organization’s day-to-day activities.

Though familiar with operations, board members expect senior leaders to excel at managing the organization with annual and three and five-year plans. At this stage, the board becomes significantly less involved in quarterly operations and performance, focusing instead on five-year and ten-year time horizons and beyond. Boards must focus on the institution’s survivability beyond any chief executive. The members broaden their scope and become genuine stewards of the organization’s tangible and intangible assets for stakeholders, the local communities, the industry, and society at large. The board shifts its main frame of reference from operations to sustainability of the business model.

When a board becomes aware of the organization’s expanded responsibilities to its local communities and society at large, it may choose to move into “mindfulness.”

A strategic board will include many of the same committees as before, with the potential addition of strategic planning, government affairs, and corporate citizenship. Board members tend to be diverse to encompass a variety of perspectives on the organization and its emerging business model. They have a strong sense of team and a passion for the organization. Recruiting new members must be a thoughtful process that takes into account experience, skills, knowledge of the business, ability to work in groups, and learning capacity.

Some dangers of a strategic board include the inability to reach decisions, unanticipated events in the operations, and the possibility that senior leaders might feel disenfranchised from the strategic thinking.

Mindful Board. When a board becomes aware of the organization’s expanded responsibilities to its local communities and society at large, it may choose to move into “mindfulness.” The mindful board knows that it needs to be conscious of more than fiscal realities. It reframes old models and structures and opens itself to new information that it may have previously discounted. Members become conscious of themselves as stewards of the organization’s assets, its culture as a reflection of its values, the quality of relationships with and among key stakeholders, and the expectations of the communities in which the organization is located. They are aware of how the organization interacts with its environment and the impact of the organization’s actions.

Members of a mindful board have a deep sense of purpose beyond providing products or services and jobs, and they have an abiding respect and affection for the institution and its potential. They explore their response to the questions, “Why does this organization deserve to operate for the next century? How will it contribute to the common good? What must we put in place (structure, values, culture, relationships, etc.) to support that purpose?” The conversation about the organization’s purpose and future design principles often occurs at a board retreat.

A board chair can’t choose for her board to move to the next level along the governance continuum.

Board members engage many other groups in a robust visioning process that embraces the creativity needed for designing the future. The mindful board expands its consciousness from the tangible fiscal world to the intangible world of purpose and spirit. At this level, the board is able to employ all four models of governance, based on the type of action needed by the board at any given time.

A New Level of Consciousness

Nonprofit boards evolve with the same expanded responsibilities as corporate boards. When I first met the board of a certain client organization, its members were all male and over 50 years old, though the organization served young women and men. The president and his staff determined the agenda for their one-day board meetings. It consisted of a parade of presentations with lunch. The president once said he never brought anything to the board for a vote that he didn’t know the outcome. This was a perfect consent board. The crisis that awakened them was a near default on their bond covenants. The board was caught totally by surprise.

As board members dug into the financial crisis, they found other surprises and moved quickly to being a working board. Interestingly, a few members resigned, saying they didn’t have time for the work. Those members were replaced by women and people with different cultural backgrounds. Through the diligence of several board committees over four years in partnership with the administration, the institution was stabilized. Recognizing all were in a different environment, the president and the board had a critical conversation about decisions taking too long and senior staff feeling overmanaged, and all agreed the board needed to pull out of operations.

The migration to a strategic board was awkward, because of tension between the board and executive team over who “owned” the strategy. By agreement, the board kept its role in crafting its own agenda, which the president had hoped to take back. The chief officer and the executive committee co-designed board meeting agendas. They successfully negotiated the development of a strategic plan, with the administration crafting and managing the annual and three-year plans, and the board focusing five years into the future and beyond.

Both the board and the executive team were anxious, because the relationship was shifting. Board members had to clarify how their work was changing and what reports they expected from administration. It took a year for both groups to settle into the new model of governance.

A fund-raising campaign ultimately awakened a deep sense of stewardship and purpose for the board. On retreat, members talked about their long-term vision for the organization. They noticed a different quality in their conversation from what they had previously experienced. In small groups, they told stories of when this board had made decisions that were based on a shared spirit and purpose. Board members talked about the crisis years as well as the last couple of years when they renegotiated their work and relationship with the organization’s administration. With a deep respect for their organization’s contribution to clients and the community, they acknowledged that the vision went well beyond 10 years and involved the sustainability of the organization’s mission beyond their lifetime. Their consciousness was engaged by service to a higher purpose – the hallmark of a mindful board. Months later, members would tell the story of that transformative retreat and why board service is a privilege at this institution. Their shift in consciousness strengthened their relationship with senior leaders from “presenting to the bosses” to “thinking about the long-term viability of the institution.” Board members and administrators expanded their perceived scope of influence. The organization has embarked on a green strategy for their buildings and are finding donors who are willing to participate financially. Together they have begun innovating on delivery of their services as they expand their relationships in the community.

A Shared Model

A board chair can’t choose for her board to move to the next level along the governance continuum. The challenge becomes surfacing the current prevailing model and identifying its impact and limitations. With a vision for the institution as well as their ideal board as a context, the members can explore what is required of them in thinking and acting as stewards for the organization. Over some period of time and conversation, the board’s collective mind begins to evolve to a new level of consciousness that incorporates the experiences from the past with the desires of the future.

While our ability to communicate may still fall short of a Vulcan mind meld, working from a shared model can help a group move faster and make the contributions it wants to make. It’s hard work to build that shared mental model. Having several options in some progression makes it easier for a group to discuss and decide on a model. Group members may choose one of the models or create their own unique model after considering the implications of the options before them.

Through their conversations, the members strengthen their capacity and weave strong connections in their relationships. It is satisfying and fulfilling work that can take the organization to a new level of stewardship and contribution.

NEXT STEPS

Building Shared Mental Models

Building shared mental models offers high leverage for change. However, it takes a great deal of perseverance to master this discipline, perhaps because few of us have learned how to build the skills of inquiry and reflection into our thoughts, emotions, and everyday behavior. Here are some tips for getting started in your organization:

- Practice Together over Time. Hold regular meetings with the same team in which you practice these skills while trying to get to the bottom of the mental models that have created chronic business problems.

- Prepare for Dealing with Strong Emotions. When the assumptions behind your models are exposed, you will be chagrined to discover that your actions (or those of your team or organization) are based on erroneous data or incomplete assumptions. Feelings such as anger, embarrassment, or uncertainty may come to the surface. Set time aside for skillful discussion about the emotions that have been raised.

- Use Frustration as a Source of New Inquiry. Teams often struggle in mental models work, even when it’s oriented to a business problem. Establish an atmosphere in which team members can bring up frustrations for inquiry.

- Beware of Excitement and Unbridled Action. When team members break through the limitations they have put on themselves and feel they can at last see the truth about themselves, their work, or their customers, they will be tempted to act immediately. Take the time to pause, reflect on strategy, and design small experiments.

Adapted from “What You Can Expect… in Working with Mental Models” by Charlotte Roberts, in The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook by Peter M. Senge, Art Kleiner, Charlotte Roberts, Richard B. Ross, and Bryan J. Smith (Doubleday/Currency, 1994).

Charlotte Roberts, PhD, is co-author of The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook: Strategies and Tools for Building a Learning Organization and The Dance of Change: The Challenges of Sustaining Momentum in Learning Organizations. She will be a keynote speaker at the 2011 Systems Thinking in Action® Conference.