It was an early November day in Massachusetts, when forecasters of both the weather and the economy agreed that the outlook was bleak. My client, Barbara, was having trouble mustering any enthusiasm for an upcoming job interview. All of the professional confidence she had amassed in 20 years as a high-performing organizational development manager had drained away during the 14 months since the sweeping recession had left her jobless.

Forced into this unfamiliar position, she was exasperated at the inadequacy of the tools that had helped her connect with employers in the past. She held up her resume and slapped at it dismissively, “I wish that when they looked at this, they could see through it to who I really am.”

I supported her frustration. “Your resume tells them what you’ve done, not who you are,” I agreed. “What kind of document could you imagine using to represent yourself in all your wholeness?”

Barbara shrugged, and we agreed that for the purposes of this interview, it wasn’t a document that she needed; rather, she would be best served to embody her whole self, bringing her full energy into the room as a force of creativity and productivity. By the end of the session, we had restored enough of a sense of wholeness to fuel her through the hiring meeting.

TEAM TIP

Reminding employees about the significance of their work can dramatically increase productivity.

But the conversation had triggered something for me – a growing recognition of how disabling it is when we limit our self-awareness to fit other people’s expectations. It wasn’t only the prospective employer who wasn’t seeing Barbara whole. Barbara herself had collapsed her focus to include only those aspects of self that she deemed marketable. In cutting herself off from a fuller picture of the complex, values-based, purposeful human being that she was, she was forfeiting significant sources of energy vital to reaching her full potential in the market.

This phenomenon is not limited to job seekers or those thrown into unanticipated mid-career transition. A limited or fragmented sense of self might be more the norm than the exception in organizational life. You see it in executives who define themselves exclusively by what they already know, ignoring the inherent power in their learning edge. You see it in rising leaders who subsume their creativity so as to better match the predetermined parameters of the next step on the career ladder. You see it in women and people of color who conceal their unique, potentially game-changing strengths under a cloak of conformity.

Asserting Your Wholeness

It is understandable why this happens to individuals. Organizational systems, geared toward productivity and profitability, have a natural preference for predictable, scalable people-management processes. From the point of hire through performance evaluation and promotion, organizations are looking primarily for fit with predefined skill sets. Even those organizations that have embraced the importance of self-awareness as a component of leadership development often rely on reductive tools and techniques for supporting it.

Leadership competency models and assessment tools such as the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, DiSC, and Herrmann Brain Dominance Instrument have undoubtedly expanded the way we think about managing the people side of complex systems. They certainly provide valuable insights about our preferences and about how we compare to others, but their very strength – the ability to deliver statistically valid and reliable comparative data – can limit our self-awareness. How? In their reliance on standardized categories, these tools can short-circuit our curiosity about our own complexity. They have us asking “Am I more like this? Or more like that?” when from time to time, we might be better served to simply ask, “What am I like?” using our own vocabulary and frames of reference to express the answers.

In his bestselling leadership book, True North, Bill George notes, “The essence of leadership comes not from having pre-defined characteristics. Rather, it comes from knowing yourself – your strengths and weaknesses – by understanding your unique life story and the challenges you have experienced.” In other words, the essence of leadership (whether of a large organization or of your own career) starts with the ability to see yourself whole, embracing a complete, accurate, and objective view of your current reality – a reality that includes constraints, but also the values and sense of purpose central to who you are. It is only from this whole-person perspective that you can make the essential connection to meaning that will fuel the journey from where you are to where you want to be.

A New Paradigm for Organizations

Likewise, a company’s ability to move from where it is to where it wants to be doesn’t reside purely in its people’s current skills, but in their collective aspirations as well. So, one might think that we would see more investment in leadership development processes and management practices that embrace the kind of inside-out self-awareness work that aligns individual values and goals to those of the organization. But for most organizations, support for individuals’ intrapersonal development focuses exclusively on “doing” gaps and avoids the mysterious “being” dimension where values, purpose, and aspiration reside. When the Fifth Discipline Fieldbook was published almost two decades ago, the authors wrote, “The enthusiasm for personal mastery has in fact outpaced the development of ideas about how to instill it in organizations.” While this is unfortunately still true, there are hopeful signs.

A company’s ability to move from where it is to where it wants to be doesn’t reside purely in its people’s current skills, but in their collective aspirations as well.

In Drive, Daniel Pink lays out a compelling case that “for too long there’s been a mismatch between what science knows and what business does,” with regard to honoring and leveraging people’s aspiration as a creative, productive force. Pink surveys the work of several researchers who have demonstrated that intrinsic motivation is the key to better outcomes. He proposes the adoption of a new “operating system” that relies not on carrots and sticks, but on strategies that engage commitment by addressing individuals’ desire for autonomy, mastery, and most important, purpose. He highlights the promising efforts of a handful of enlightened companies such as Best Buy, Google, and Zappos that are experimenting with management practices designed to foster a work culture that recognizes the wholeness of the individual. On the leadership development front, the steady increase in the use of coaching as a tool for amplifying possibility as opposed to simply addressing poor performance may be the strongest signal of all that an important shift in talent management practices is underway.

Yet even as organizations slowly learn how to create the conditions in which self-knowledge is honored as essential to both individual fulfillment and team success, it will always be our own responsibility as individuals to be aware of our whole selves, because we are the only ones who can ensure that what has meaning for us is at the center of what we are producing. As coaches, consultants, and managers promoting more people-centered organizational paradigms, the work ahead involves building partnerships – between individuals with the courage to see themselves whole and organizations that recognize the value that whole people are capable of creating.

Systems Thinking Principles for Individual Wholeness

A few years ago, when I decided to segue from my communications and community-building role with Pegasus to work more directly with individuals in the realm of personal mastery, I investigated the handful of respected coach training programs that seemed most compatible with a systems thinking perspective. For a variety of reasons, I opted to pursue certification in the Co-active® model and immediately felt at home with the “whole being” orientation of the approach. The framework is adaptable to a variety of individual change contexts such as executive coaching, leadership development, and career development. In its recognition of the synergistic coaching relationship (and not the coach) as the power source for change, the co-active model is predicated on the idea of the whole being greater than the sum of its parts.

Within this framework, clients deepen their awareness of the systems that they’re in – beginning with the systems that they are. When I start a relationship with a new client, I sometimes provide them with a toy spyglass (either real or imagined) to get them thinking about the vantage point from which they are regarding their current challenges. It is a playful gesture to remind them that as their coach, I will always be holding the broadest possible perspective on their potential as a whole human being. It also sends the clear message that I will be challenging and supporting them in the regular practice of zooming out to get their whole system of self into the picture.

I perceive three tangible benefits from maintaining a whole-self perspective. First, from this kind of reflection, people get clearer about what matters most to them. In naming what matters, they may uncover internal “saboteurs” that push them to compromise their values in the name of expedience or pragmatism. They might recognize storylines in their lives reminiscent of Marlon Brando’s famous speech in On the Waterfront where his character sadly regrets taking a dive during a boxing match “for the short-end money.” The broader, longer-term perspective helps clients make choices that don’t leave them thinking “I coulda’ been a contender – if only I had taken action more in line with my real values or my real purpose.” Maintaining a whole-self perspective helps people keep their vision and values alive in the choices they make and the actions they take.

In a second systems-based inquiry, I might help clients explore whether short-term fixes are diverting them from more sustainable solutions by asking, “What pattern can you see at work here?” Say, for example, that a client is unhappy with her staff’s performance in preparing reports for the board of directors. She is experiencing burn out and fatigue because she repeatedly opts to do the reports herself, seeing this as less time consuming than training others in her preferred approach. When she zooms out to the pattern level, she recognizes some interesting loops: The more fatigued she gets, the less tolerance she has for her staff’s sub-optimal work; the more she expresses her dissatisfaction with their work, the less confidence they have in their capacity to do it; the more she takes on herself, the less invested and accountable the staff feels for the work at hand. By inquiring into the pattern, she has illuminated for herself the link between her fatigue and her reluctance to spend the time required to engage and train her staff. Maintaining a whole-self perspective helps people look for root causes, instead of trying to solve problems at the symptom level.

A third systems principle that demonstrates the value of seeing yourself whole is the leverage point – a small change in one area that triggers improvements across other aspects of the system. For example, with the current high unemployment rate, many of us have worked with clients like Barbara (mentioned above) who have been out of work for more than a year. They are understandably obsessed with this dilemma and spend the majority of their time focusing on it. When we urge these clients to take stock of the whole system of self, they may see, for example, that their health is also a problem, one that they’ve been putting off dealing with because they tell themselves, “I’ve got to get a job first.” This may be a leverage point for change, in that when people improve their health, they may increase their effectiveness in their job search. With the whole system in view, they can see that sometimes the harder they push on the presenting problem, the more it pushes back. Maintaining a whole-self perspective helps people discover leverage points for intervening when they’re stuck or off-track.

The “Seeing” in Seeing Yourself Whole

As a visual learner naturally drawn to maps and images, I like to help people deepen their self-reflection and inquiry about the system of self by literally making a picture of it.

When I am working with a seasoned systems thinker, I might recommend that they experiment with depicting the system of self using some of the systems mapping tools that we use to diagnose organizational systems. But for many clients, stock and flow or causal loop diagrams can seem overwhelming in their complexity and technicality. I recommend they make a simpler picture as a good first step.

A Life-Balance Wheel

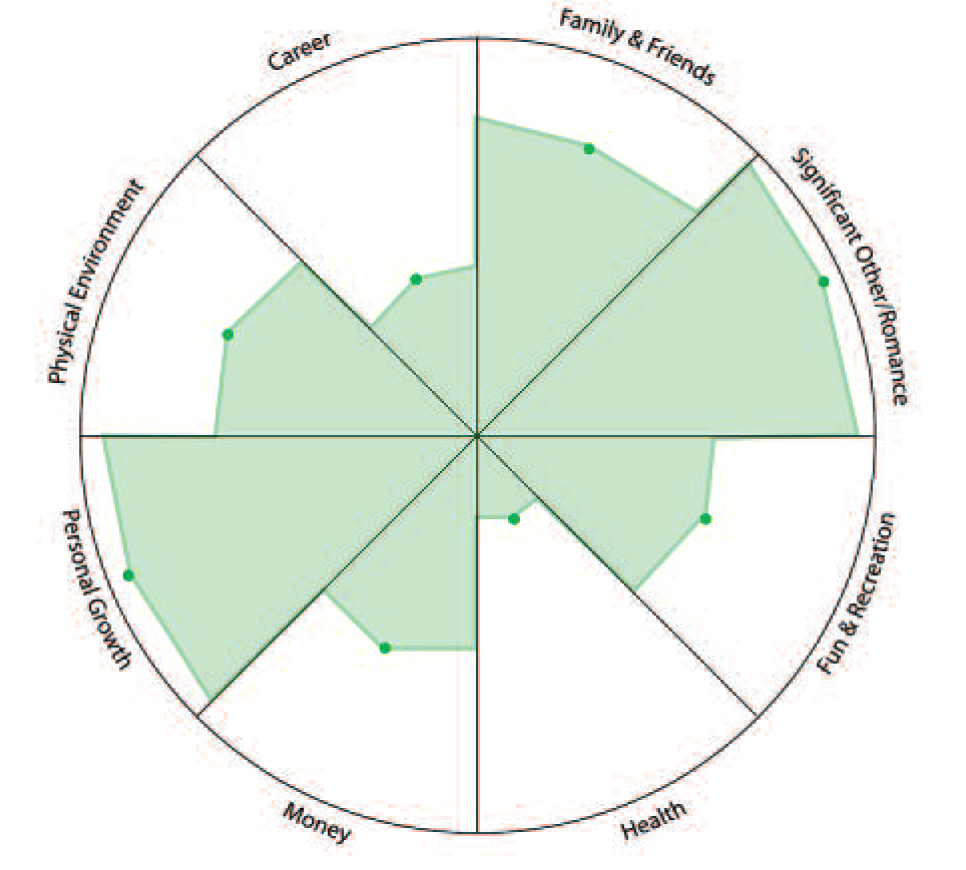

SAMPLE LIFE-BALANCE WHEEL

A wheel, divided into segments that correspond to different aspects of people’s lives, allows users to identify opportunities for increasing their overall level of fulfillment and satisfaction.

Many coaches use a wheel-like image to help clients step back and take the “forest” rather than the “tree” perspective on life (see Sample Life-Balance Wheel”). The wheel, divided into segments that correspond to different aspects of people’s lives, allows users to identify opportunities for increasing their overall level of fulfillment and satisfaction.

Assuming that the center of the wheel is the zero point and the outer edge is a ten, the client places a dot in each segment indicating how satisfied they are in that area, with zero being completely unsatisfied and ten being completely satisfied. The user can then draw lines to connect the dots and shade in the resulting footprint to produce a picture of their overall satisfaction level at any given point in time.

This kind of image can deliver some interesting epiphanies. Remember the leverage points example mentioned earlier, in which a long-unemployed individual was ignoring her health issues to focus relentlessly on her unemployment status? When their choices are made visible, people often recognize opportunities for leverage and balance across the system.

I’ve seen other interesting breakthroughs with this tool. For example, sometimes people realize that despite low scores in some areas, they have very high scores in others. This reminds them that they have a well of strength that they can continue to draw on in addressing the gaps. Another thing that happens is that people see patterns. For example, someone might rate their satisfaction high in Significant Other and Family and Friends but low in Health and Personal Growth, and ask, “Am I choosing to focus on other people in my life and neglecting my own needs?” There’s tremendous power in putting a picture of the whole system in front of you so that you can better gauge how you’re out of balance, where you’re focusing your attention, and where change might be possible.

The Round Resume

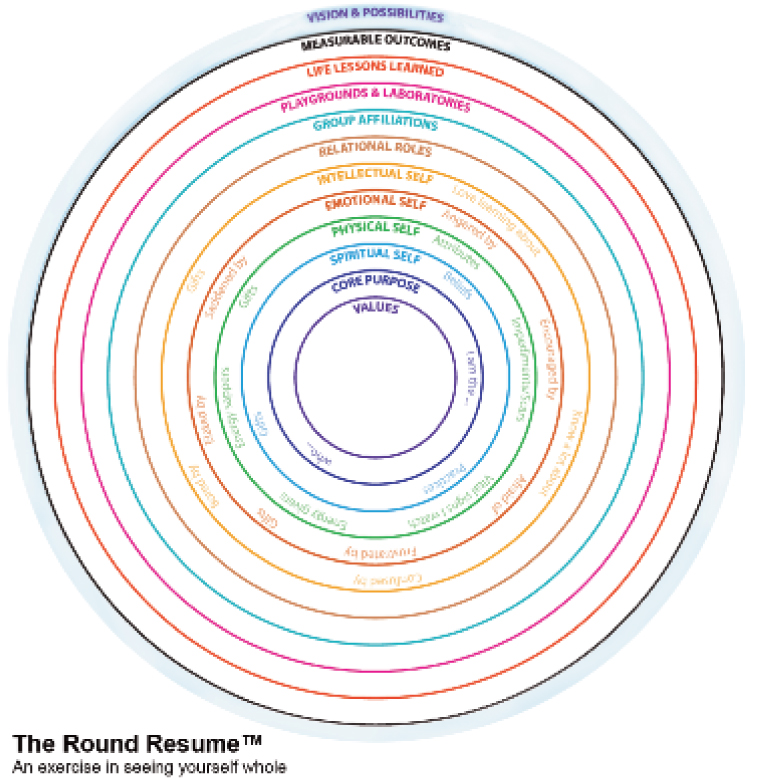

SAMPLE ROUND RESUMÉ

In using the Round Resume, people reflect on a series of questions to create a self-portrait that celebrates their wholeness and complexity.

A second visual tool that I use to support clients in seeing themselves whole centers more on “being” than “doing” as it illuminates the meaning that holds the system of self together. This tool, the “Round Resume,” grew out of my desire to answer the question that I had asked Barbara when she expressed her frustration about the inadequacy of her resume: “What kind of document could you imagine using to represent yourself in all your wholeness?”

As I sat with that question, the first thing that came to mind was a mandala. The mandala is a visual form that I had been introduced to by my late Aunt Cynthia, who toward the end of her life had adopted a practice of drawing mandalas and reflecting upon them to uncover the prayers they evoked in her. With roots in several ancient spiritual traditions, a mandala – which means “circle” in Sanskrit – is a round, symmetrical design, representing a sacred space or a unified whole. Carl Jung used mandalas in his work with patients, viewing the form as “the psychological expression of the totality of the self.”

With this in mind, I embarked on an iterative, experimental design process and, with input from several clients and colleagues, developed a mandala-like template built on a series of fundamental coaching questions: What matters to me most? What is my purpose? Who am I? I now use the Round Resume as the centerpiece of a 2½- hour facilitated process during which clients reflect on the answers to these questions to create a self-portrait that celebrates their wholeness and complexity (see “Sample Round Resume”).

The Meaning That Makes the System Hum: Core Values. At the center of the Round Resume, clients record a vibrant sampling of their core values, those qualities of life that they recognize as having paramount meaning for them.

Most of us would say that we know what our core values are, at least unconsciously. But naming those values and putting them in writing allows us to amplify our conscious awareness of them, remember what’s important about honoring them, and notice how we bring them to life in the choices that we make.

To get clients started on defining their own core values, I sometimes have them look at pictures in which the values of others are readily apparent. For example, a picture of cyclists in full regalia competing against each other on the open road might evoke values of freedom, competition, design (those colorful costumes!), and speed. A picture of physicians from Doctors Without Borders attending to a Haitian woman’s injuries might evoke values of compassion, personal responsibility, and resourcefulness. As I share each picture, I ask, “What are the values you see getting honored in these images?”

Then, using a guided visualization technique, we revisit peak moments and crisis moments from the client’s life to reveal how his or her values have made themselves known through resonance and dissonance.

The Fuel That Drives the System Outward: Core Purpose. Closely related to that unique blend of values at our core is the idea that each of us is perfectly suited – with those values and with our particular gifts and sensitivities – to make a difference in the world that no one else can make. During a recent visit to the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, Massachusetts, I learned that the renowned illustrator had a clear sense of his core purpose from the age of five when he first encountered colorful paints and big, white sheets of paper. Of course, most of us haven’t enjoyed that kind of lifelong clarity. But by reflecting on the question of impact, we can often discern a thread of purpose that’s evident in everything we do.

Consider the example of legal scholar Clare Dalton who in 1987 won a sex discrimination suit when her employer, Harvard University Law School, denied her tenure. Using her settlement money to start a domestic violence research and education institute at Northeastern University Law School, Dalton continued to thrive, winning acclaim in the area of domestic violence law. But about a year ago, after a five-year course of studies, Dalton radically changed gears and opened an acupuncture practice. In a profile in The Boston Globe, Dalton is quoted as saying, “As a teenager, I was really interested in Eastern philosophy and alternative healing. Now I feel as if I’ve gone back to the 17-year-old me and am taking the path I didn’t take then.” Notice the thread of healing that runs through both of Dalton’s career choices – from working to improve the way our society supports abused women to providing hands-on healing services.

Using the Round Resume to help clients uncover their own core purpose, I again walk through a guided visualization technique to surface some of the central themes of their lives. The client crafts a metaphorical statement that captures their impact. For example, one client wrote, “I am the window through which others see their potential.” Another wrote, “I am the architect who builds a safe and supportive thriving space where change is possible.”

Four Dimensions of Self

After clients have entered their core values and core purpose into the center of the template, the next step is to look at how these essential elements of self find expression in every dimension of their beings. As humans, we understand that we are multi-dimensional beings, but we tend to disaggregate ourselves when we think about who we are. Our awareness shifts as we move from place to place in our lives. We might think of ourselves as primarily bringing our heads to work, leaving our hearts at home, taking our bodies to the gym, and bringing our spirit for a walk in the woods. But it’s important to remember that no dimension of self ceases to exist just because we’re not paying attention to it. As complex living systems, who we are – and how we are – is the product of the continuous interoperation of our intellectual, emotional, physical, and spiritual energies.

A wise client of mine once described our limited focus as somewhat like being a spider caught in the web of our own system. We see ourselves only one piece at time, and frequently with judgment rather than curiosity and appreciation.

The Round Resume challenges people to hold four dimensions of self in their awareness concurrently, looking objectively at their own thought processes, emotions, bodies, and spirits, and taking a break from being subject to their assumptions about each. I frame the exercise not as a chance to describe what you “know” about yourself, but rather as a chance to describe what you “notice” about who you are in these four dimensions.

People are less likely to get judgmental and stuck when they use their values and purpose as a guide to this inquiry. For example, say someone names a core value of humility. When I ask, “How is the value of humility active in your physical self? In your emotional self? In your intellectual self? And in your spiritual self?” the client looks with curiosity rather than certainty. This puts her in a stance from which she can observe how her values animate every aspect of her being, and she can also notice how her self-defeating habits are rooted in values-based stories.

Outward from Self

Building on these inward-focused reflections about self, the Round Resume then invites clients to zoom out with a wider lens to explore how their values and purpose animate the boundaries that delineate their interdependence with others and with their environment.

The process concludes with a brief shared acknowledgment that the measurable outcomes listed on the client’s conventional resume were not created in a vacuum, but rather reflect the wholeness of the person who created them. Together, we observe how those outcomes do or do not seem to be imbued with the client’s values and purpose. I ask, “What do you want to do more of? What do you want to do less of? As you move forward into the realm of vision and possibility, what do you want to do next as an evolution or a wholly new expression of your values and purpose?”

When working with clients in an organizational context, I ask, “How are your values and purpose serving your organization?” “How do your values and purpose align with the values and purpose of the organization?” “What do you want to create for this organization?”

A Matter of Practice

These tools offer just a few possible techniques for embarking, and helping others embark, on the “inward-bound journey” that, as Peter Senge and his co-authors observe in the book Presence, “lies at the heart of all creativity, whether in the arts, in business, or in science.” These tools are a good starting point, but they are just that: a start. The business of seeing yourself whole is not a one-time achievement, but rather an abiding perspective that must be practiced with persistence and resolve. When you maintain your awareness of self as a complex, dynamic whole, the rewards that accrue to you and those around you are immeasurable: You expand your options for intervening when you’re stuck or off-track; you gain clarity about the values that enliven you and the purpose that drives you forward; you gain confidence in your capacity for sustained creativity and productivity; you gain fluency in the stories of your life. By doing so, you say yes to making the difference that only you can make, the one the world needs from you now.

Vicky Schubert, ACC, CPCC, is a certified coach with 15 years of senior management experience in the field of organizational learning and development. As the principal of Inspired Alliance, she coaches leaders, agents of change, and individuals in transition on deepening their sense of fulfillment and purpose while amplifying their professional impact. Before establishing her coaching practice, Vicky led marketing and community-building efforts for Pegasus Communications and the Society for Organizational Learning. She previously was a partner with Options for Change Consulting.