T he Double-Loop Learning Matrix (adapted from the work of John J. Shibley) is a tool that teams can use for uncovering and articulating high-leverage change initiatives. This matrix is an integration of three vital learning tools: (1) the phases of the classic learning cycle — observe, assess, develop, implement; (2) Chris Argyris’s double-loop learning framework; and (3) the levels of understanding of systems thinking as articulated by Daniel H. Kim — events, patterns, structure, mental models, and vision.

At Gerber Memorial Health Services (GMHS), we used the Double-Loop Learning Matrix to transform our customer service culture from

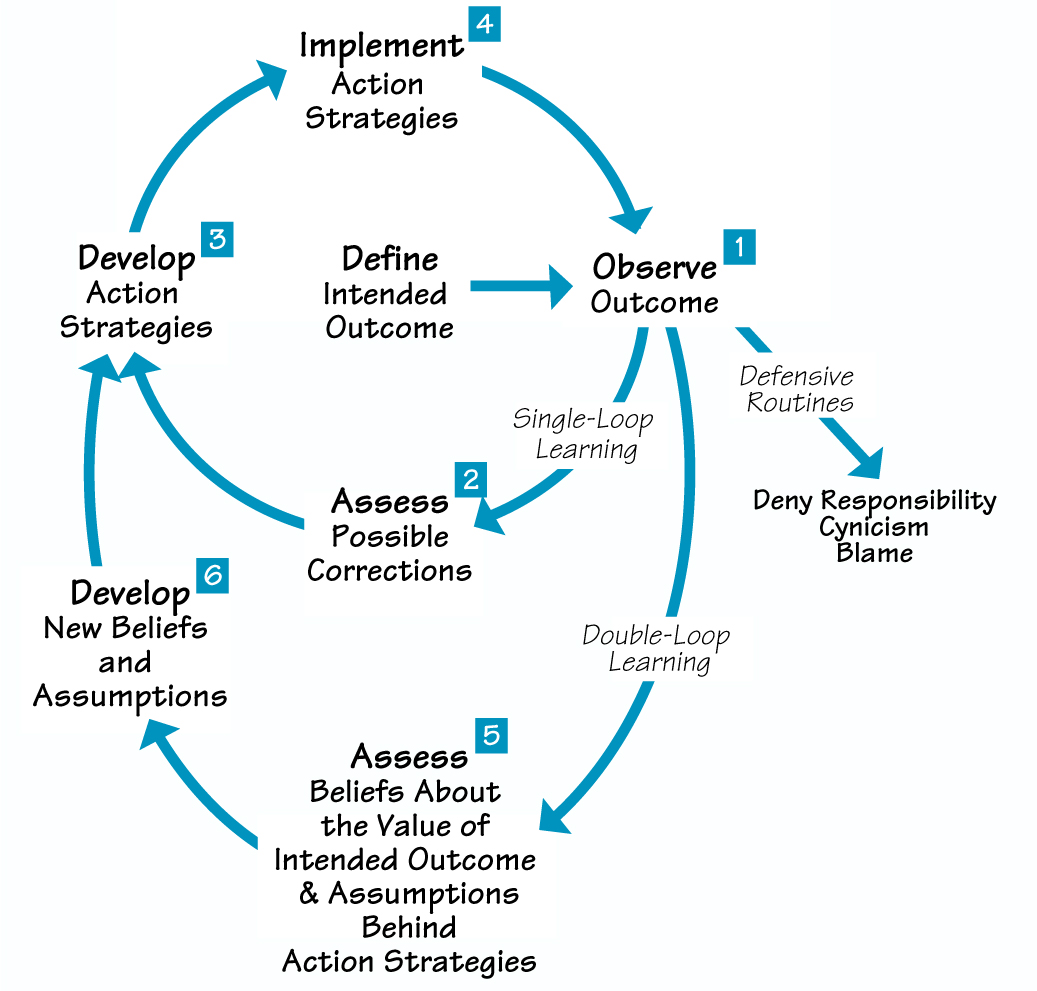

TWO LEARNING CYCLES

“What customer service problem?” to “Our customer service problem is deep, wide, hidden, and misunderstood.” This shift enabled us to look for fundamental solutions, rather than justify our current performance or attempt more quick fixes.

Single and Double-Loop Learning

Single-Loop Learning Cycle. The classic learning cycle begins by identifying the intended outcome of the change initiative and then observing the actual outcome (step 1 in “Two Learning Cycles”). When we notice a gap between the two, we become motivated to consider ways to close that gap. We assess possible corrections (step 2) and develop (step 3) and implement (step 4) action strategies. After we implement these strategies, we again observe the results (step 1) to see if the strategy we implemented came closer to achieving our desired outcome. However, with most difficult problems, this approach will provide us with only temporary success.

Double-Loop Learning Cycle. After following the single-loop cycle through several rotations with only limited success, we may come to find that we need to dig deeper into the problem. To be effective, we need to shift to double-loop learning. Instead of assessing additional corrections (step 2), we must assess our beliefs about why we value the intended outcome and why we assumed the previous strategy would work (step 5). Uncovering the answers to these questions will lead us to develop new beliefs and assumptions (step 6) about what we want to achieve and the best way to achieve it. From there, we can develop new, more effective action strategies (step 3). This is difficult work. When participants perceive issues as threatening or embarrassing, defensive routines may kick in, resulting in denial of responsibility, cynicism, or blame, all of which hinder learning.

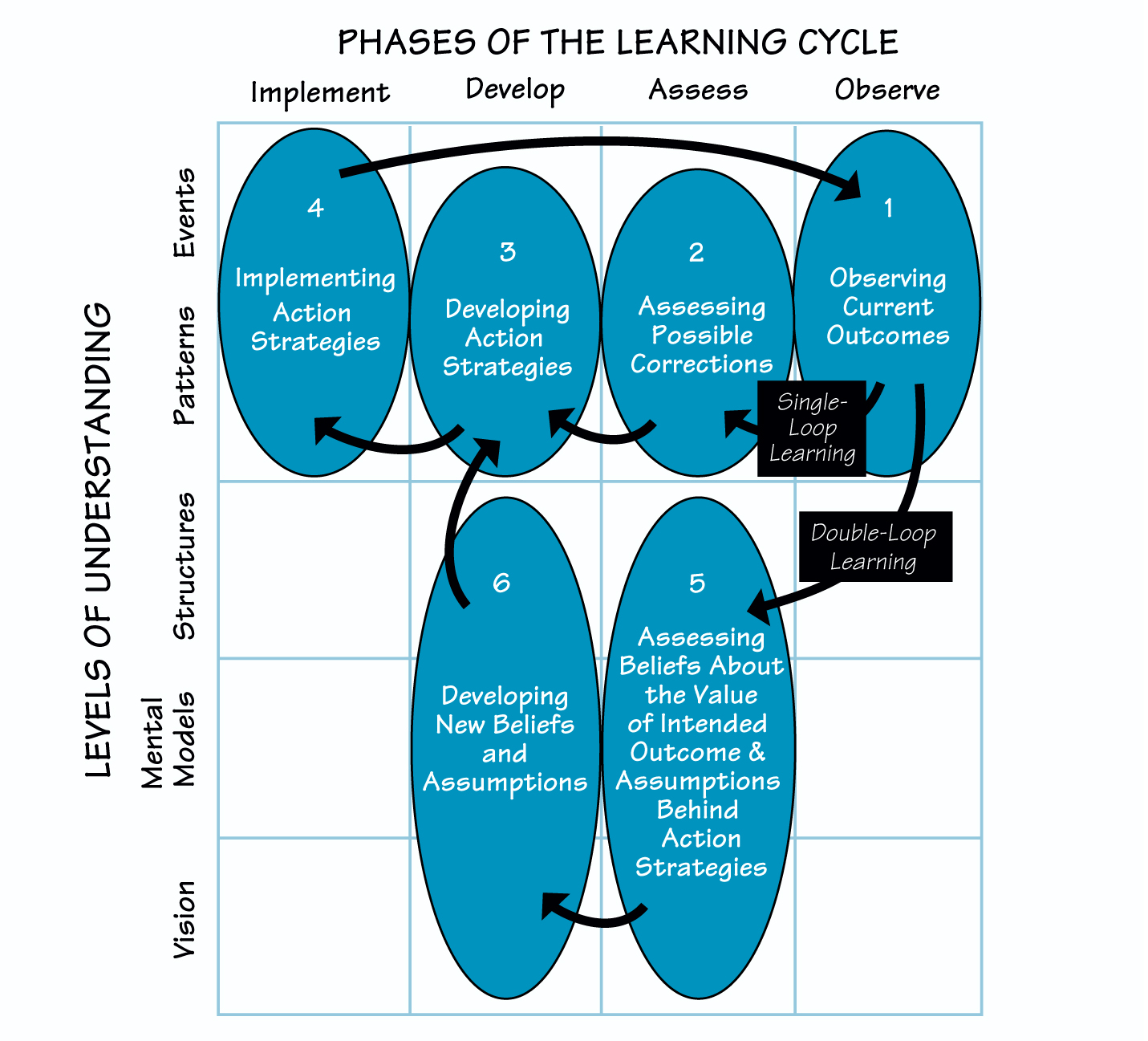

Learning Matrix

When we superimpose the double-loop learning cycle on the systems thinking framework, we create “leverage zones” (see “Double-Loop Learning Matrix”). Actions in Zones 1–4 are generally low-leverage approaches to a problem; Zones 5 and 6 are the, “high-leverage zones.” By linking the uncovering and testing of beliefs and assumptions in double-loop learning and systems thinking/mental model work in the matrix, we can draw attention to the fact that systems work at this level is about making our causal assumptions explicit and visible — and thus testable. Also, joining the two concepts in this way points to the difficult work of the sixth zone, that of actually creating new belief systems. By adding the systems thinking framework, we facilitate double-loop learning by explicitly moving from “event and pattern thinking” to the “high-leverage zones” of structures, mental models, and vision e “high-leverage.

Events and Patterns. Our typical problem-solving orientation usually keeps us at the level of events (“What happened?”) and patterns (“What’s been happening?”) — a single-loop learning process. We often go through all four steps of the learning cycle at the events/patterns level.

Structures. When we venture down into the structure level, we begin asking more difficult questions — questions of ourselves — such as “What are we doing that causes this pattern to continue to happen?”

Mental Models. At the level of mental models, we ask ourselves, “What makes us think that the strategies we selected will actually result in the outcomes we desire?” and “What beliefs do we hold that cause us to value this intended outcome?”

Vision. At the level of vision, we ask ourselves, “How does our ‘picture of the future’ affect our achievement of the intended outcome?” Here, we are clarifying what we want to create together.

Addressing Customer Service Problems

GMHS attempted various single-loop “solutions,” such as communicating with waiting patients every 30 minutes, to attempt to address a recurring customer service problem. These actions had some short-term positive results before the same indications of poor customer service returned with a vengeance. The Customer Orientation Strategic Team finally realized that, by focusing on reviewing case studies (events level) and data trends over several years (patterns level), we were working exclusively in Zones 1-4. Although this analysis was necessary and helpful, the group recognized that it needed to “go to Zone 5” to get more leverage to address these ongoing problems.

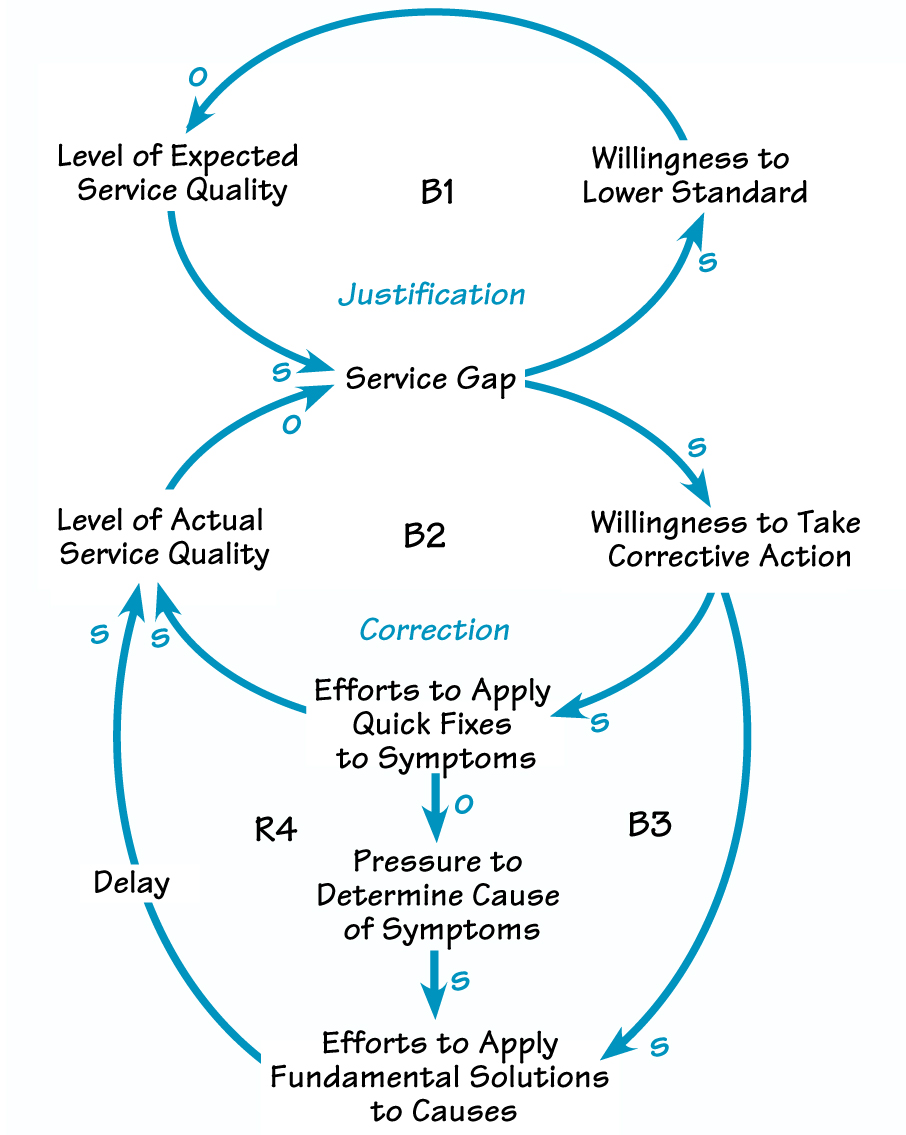

Zone 5. We started by using the “Drifting Goals” and “Shifting the Burden” archetypes (structure level) to answer the question “What are we doing that causes this pattern of poor performance to continue to happen?” The group recognized that whenever we noticed a service gap (the difference between our expected and actual level of service quality), we tended to either lower our service standards (B1in “Failed Fixes for the Service Gap” on p. 8) or apply quick fixes to the symptoms (B2). In addition, the more quick fixes we attempted, the less likely we were to apply fundamental solutions (R4) — a vicious cycle.

DOUBLE-LOOP LEARNING MATRIX

Next, we explored the question “Why do we keep thinking that our strategies will actually result in improved customer service?” (mental models level). We discovered three factors that contributed to the failure of previous attempts: (1) low level of ownership for the problem, (2) low-level of priority given to service quality, and (3) low level of empowerment of associates. We used causal loop diagrams to show how we could increase Priority, Ownership, and Empowerment, which would make GMHS less likely to justify poor performance and more likely to correct poor performance with fundamental solutions.

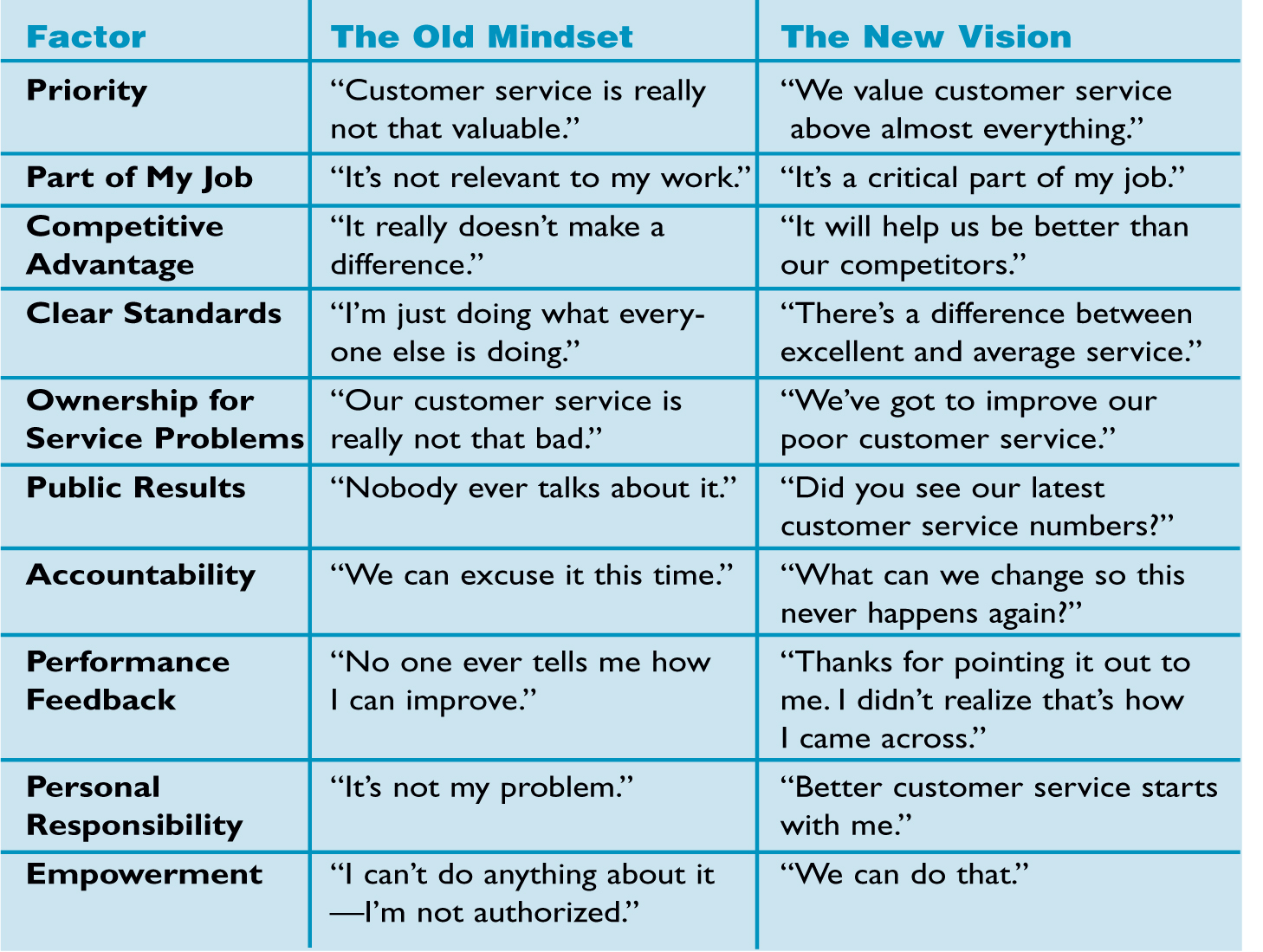

Then, we posed the question, “What have we been trying to create here?” (vision level). At first, we couldn’t clearly articulate what we wanted customer service to be like at GMHS. In other words, we didn’t have a concrete vision; we had a defensive, cynical mindset.

FAILED FIXES FOR THESERVICE GAP

Zone 6. We recognized that, in order to implement fundamental solutions, we needed new structures, new mental models, and a new vision. We used the “Framework for Service Quality” as our new structure. Our new mental model became, If we don’t increase priority, ownership, and empowerment, we will most likely lower our standards or look for quick fixes.” Our new vision is illustrated in “Our Old Mindset and Our New Vision” on p. 8.

Zones 3 and 4. We then began developing and implementing new action strategies focused on addressing the factors related to ownership, priority, and empowerment. For instance, we raised the “priority” of service quality by developing clear standards, training the entire organization, and incorporating the standards into everyone’s job description. We increased “ownership” for service quality by making customer survey results public to associates and developing a tool called a “Learning Plan” that helps managers hold associates accountable for departmental results.

OUR OLD MINDSET AND OUR NEW VISION

Performance Improvement Traction

Zone 1. Finally, we asked ourselves if using the “high-leverage zones” approach made a difference in solving our customer service problem. We concluded that it did. For example, in our Med/Surg department, in 1998, only 90 percent of patients surveyed said they would recommend GMHS to friends and family. In 2001 (on a slightly different scale), 100 percent of patients surveyed said the likelihood of their recommending GMHS to others was “good” or “very good.” Anecdotal evidence of improvement also abounds throughout our organization.

The use of the Double-Loop Learning Matrix provided GMHS with a framework to help us look at how our thoughts and actions were preventing us from applying fundamental solutions to our ongoing customer service problem. Learning in Zones 5 and 6 is more about who you are as an organization and less about what you do. We might think of these as “reflection zones,” as compared to Zones 1-4, which we might think of as “action zones.” Working in the reflection zones is difficult, messy, and well worth the effort.

As organizations look for ways to improve their performance, many will continue to run on the single-loop learning treadmill. When groups become frustrated with this approach, they will desire more fundamental solutions. Deliberately cultivating double-loop learning using tools such as the Double-Loop Learning Matrix may provide the necessary framework to help them stop spinning their wheels and start getting some performance improvement traction.