We hear a lot about complexity in the business world today — specifically, that increasing complexity is making it tougher than ever for companies to establish and maintain their competitive positioning and to sustain the pace and level of innovation they need to survive. But what exactly is it that makes a company complex, and how should an organization deal with it? If we take an inside look at Ford Motor Company, we can see what complexity actually looks like in action.

With a total of 300,000 employees, Ford operates in 50 countries around the world. It sells a huge array of products, and offers an equally widespread range of services — from financing to distributing and dealer support.

VENTURING INTO THE BADLANDS

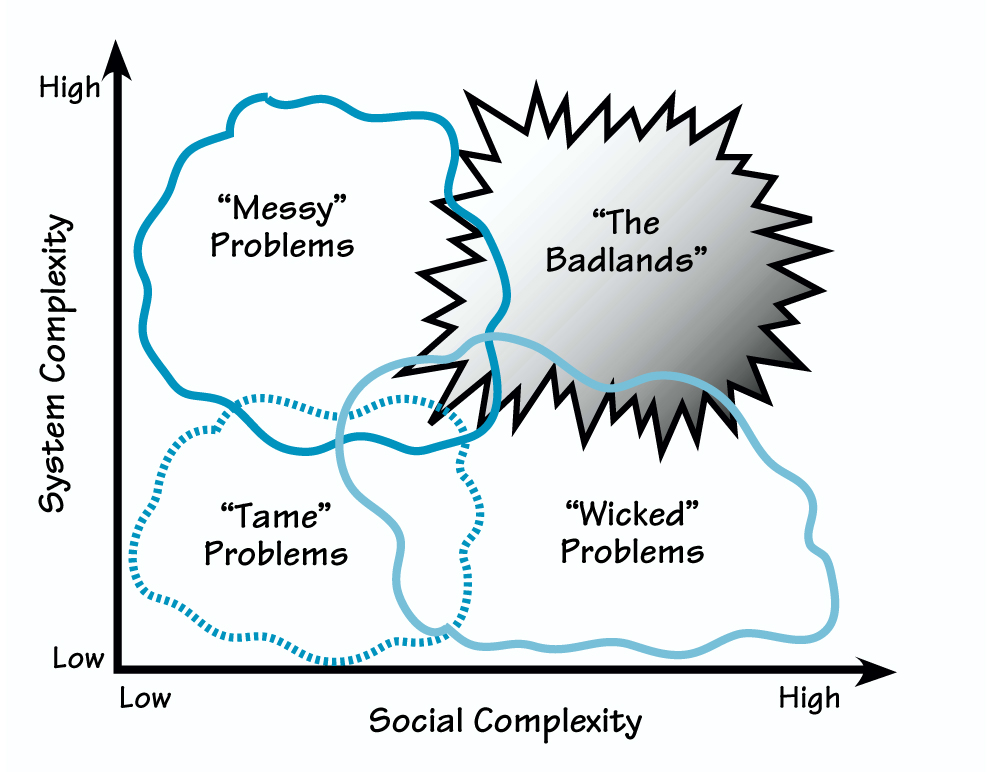

When system and social complexity are high, the organization enters the realm of “the Badlands.”

Like any large organization, it’s also peopled by individuals who come from all walks of life — and who have the different outlooks to prove it. Engineers, accountants, human-resource folks — they all have unique backgrounds and view their work through unique perspectives. Add Ford’s various stakeholders to the mix, and you’ve got even more complexity. There are media stakeholders, shareholders, customers, the families of employees — all of them with different expectations and hopes for the company.

System and Social Complexity: “The Badlands”

Now let’s look even more deeply inside Ford to see what complexity really consists of. If you think about it, the complexity that Ford and other large organizations grapple with comes in two “flavors”: system complexity and social complexity. System complexity derives from the infrastructure of the company — the business model it uses, the way the company organizes its various functions and processes, the selection of products and services it offers. Social complexity comes from the different outlooks of the many people associated with Ford — workers, customers, families, and other stakeholders from every single country and culture that Ford operates in.

Why is it important to distinguish between these two kinds of complexity? The reason is that, if we put them on a basic graph, we get a disturbing picture of the kinds of problems that complexity can cause for an organization (see “Venturing into the Badlands”). We can think of these problems as falling into four categories:

“Tame” Problems. If an organization has low system and social complexity — for example, a mom-and-pop fruit market in a small Midwestern town — it experiences what we can think of as “tame” problems, such as figuring out when to order more inventory.

“Messy” Problems. If a company has low social complexity but high system complexity, it encounters “messy” problems. A good illustration might be the highly competitive network of tool-and-die shops in Michigan. These shops deal with intricate, precisely gauged devices that have to be delivered quickly. However, the workforce consists almost entirely of guys, all of whom root for the Detroit Lions football team — so there’s little social tension.

“Wicked” Problems. If a company has high social complexity but low system complexity, it suffers “wicked” problems. For instance, a newspaper publisher works in a relatively simple system, with clear goals and one product. However, the place is probably staffed with highly creative, culturally diverse employees — with all the accompanying differences in viewpoint and values.

The Winner: “Wicked messes,” or “The Badlands.” When an organization has high system and social complexity — like Ford and other large, globalized companies have — it enters “the Badlands.” Singer-songwriter Bruce Springsteen graphically captured that unique region in South Dakota characterized by dangerous temperature swings, ravenous carnivores, and uncertain survival in his song “Badlands.” But the area and the song also represent optimism and possibilities. More vegetation and wildlife inhabit the Badlands than anyplace else in the United States, and Springsteen’s voice and lyrics offer a sense of hope despite the song’s painful and angry chords.

What’s So Bad About the Badlands?

A company that’s operating in the Badlands faces a highly challenging brand of problems. The complexity is so extreme, and the number of interconnections among the various parts of the system so numerous, that the organization can barely control anything. Solutions take time, patience, and profound empathy on the part of everyone involved.

In Ford’s case, a number of especially daunting challenges have arisen recently. For one thing, the Firestone tires tragedy has left the entire Ford community reeling. Ford faces an immense struggle to make sure this kind of fiasco never happens again. The bonds of trust between company and supplier, and between company and customer, will take a long time to rebuild. In addition, Ford and other automotive manufacturers have come under fire not only for safety issues but also for environmental and human-rights concerns.

Clearly, Ford’s business environment keeps getting tougher. The company is held accountable for parts it buys from suppliers and for labor practices in the various parts of the world where it does business. It’s also accountable for resolving baffling patterns — for example, the demand for

All of these challenges come from a single error in thinking: the assumption that human beings can control a complex, living system like a large organization.

SUVs is rising, along with cries for environmentally friendly vehicles. The majority of Ford’s profits come from sales of SUVs; how will the company reconcile these conflicting demands? Ford’s newly launched initiative — to not only offer excellent products and services but to also make the world a better place through environmentally and socially responsible manufacturing — will probably be its toughest effort ever.

But here’s where the big lesson comes in. All of these challenges come from a single error in thinking: the assumption that human beings can control a complex, living system like a large organization. Systems thinker Meg Wheatley compares the complexity of large companies to that of the world. The world, she points out, existed for billions of years before we humans came along, but we have the nerve to think that it needs us to control it! Likewise, what makes us think that we can control a big, complex organization?

Yet attempt to control we do — often with disastrous results.

Our All-Too-Common Controls . . .

We human beings try to control the complexity of our work lives through lots of different means:

System Fixes. When we attempt to manage system complexity, we haul out a jumble of established tools and processes that seem to have worked for companies in the past. For example, we use something we blithely call “strategic planning.” Our assumption is simple: If we just write down the strategy we want to follow, and plan accordingly, everything will turn out the way we want. We even call in consultants to help us clarify our strategy — and pay them big bucks for it. The problem is that this approach to planning has long outlived its usefulness. The world has become a much more complicated place than it was back when organizations like General Motors and the MIT Sloan School of Management first devised this approach to strategy.

We also use financial analysis and reporting models that were probably invented as far back as the 1950s. These models don’t take into account all the real costs associated with doing business — such as social and environmental impacts. Nor do they recognize the value of “soft” assets, such as employee morale and commitment.

In addition, we all keep throwing the phrase “business case” around — “What’s the business case for that new HR program you want to launch?” “What’s the business case for that product modification?” In other words, what returns can we expect from a proposed change of any kind? Again, this focus on returns ignores the bigger picture: the long-term costs and benefits of the change.

Finally, we try to manage system complexity by making things as simple as possible through standardization — no matter how complicated the business is. Standardization is appropriate at times. For example, the Toyota Camry, Ford’s number-one competitor in that class of car, has just seven kinds of fuel pump applications. The Ford Taurus has more than 40! You can imagine how much simpler and cheaper it is to manufacture, sell, and service the Camry pump. But when we carry our fondness for standardization into areas of strategy — unthinkingly accepting methods and models that worked best during a simpler age — we run into trouble.

Social Fixes. Our attempts to manage social complexity get even more prickly. In many large companies, the human-resources department engineers all such efforts. HR of course deals with personnel planning, education and training, labor relations, and so forth. But in numerous companies, it spearheads change programs as well — whether to address work-life balance, professional development, conflict and communications management, or other social workplace issues. Yet as we’ll see, this realm of complexity is probably even more difficult to control than systemic complexity is.

. . . and Their Confounding Consequences

Each of the above “fixes” might gain us some positive results: We have a strategic plan to work with; we have some way of measuring certain aspects of our business; we manage to get a few employees thinking differently about important social issues. However, these improvements often prove only incremental. More important, these fixes also have unintended consequences — many of them profound enough to eclipse any gains they may have earned us.

The Price of System Fixes. As one cost of trying to control system complexity, we end up “micromanaging the metrics,” mainly because it’s the only thing we can do. This micromanaging in turn creates conflicts of interests. For example, when Ford decided to redesign one of its 40 fuel pumps to make it cheaper to build, it unwittingly pitted employees from different functions against each other. Engineering people felt pressured to reduce the design cost of the part, manufacturing staff felt compelled to shave off labor and overhead costs, and the purchasing department felt driven to find cheaper suppliers. Caught up in the crosscurrents of these conflicting objectives, none of these competing parties wanted to approve the change plan unless they got credit for its success. As you can imagine, the plan languished in people’s in-boxes as the various parties jockeyed for position as “the winner.”

Micromanaging the metrics can also create a “Tragedy of the Commons” situation — that archetypal dilemma in which all the parties in a system try to maximize their own gains, only to ruin things for everyone. For instance, at Ford (and probably at many other large companies), there’s only so much money available to support a new product or service idea. People know this, so when they build their annual budgets, they ask for the money they need for the new ideas — plus another 10 percent as a cushion (because they know the budget office would never give them what they originally asked for!). At the end of the year, everyone’s out of funds because they beefed up their budgets too much. And great, innovative ideas end up going unfunded.

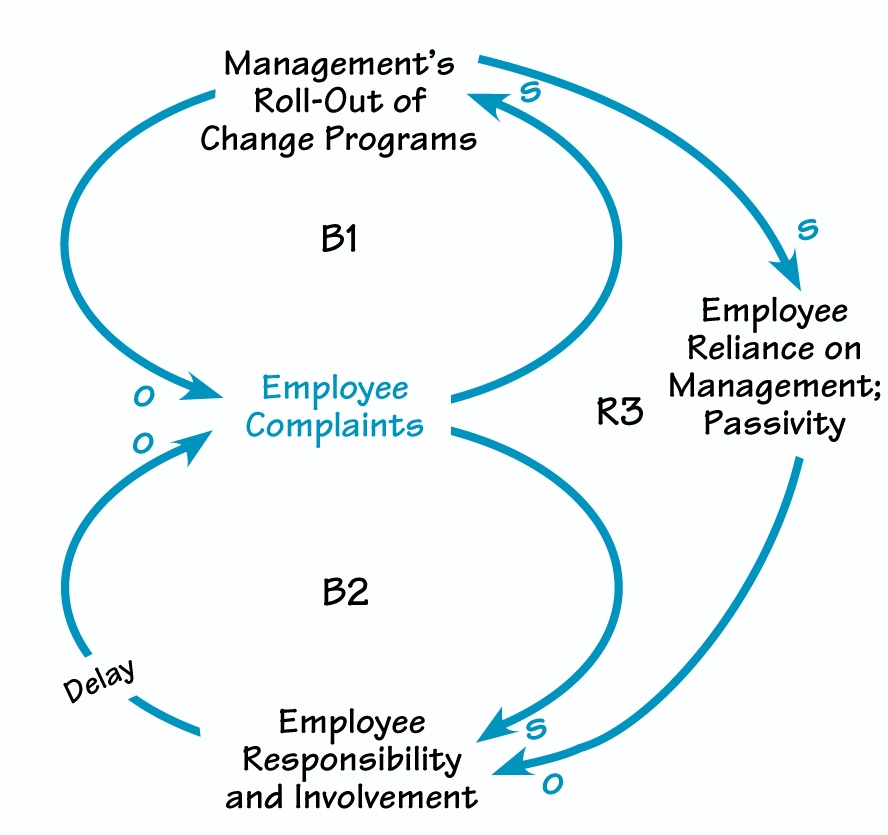

The Price of Social Fixes. The biggest consequence of social fixes is probably a “Shifting the Burden” archetypal situation. Upper management, along with HR, tries to address a problem by applying a short-term, “bandage” solution rather than a longer-term, fundamental solution. The side effect of that bandage solution only makes the workforce dependent on management, thus preventing the organization from learning how to identify and implement a fundamental solution.

What does this look like in action? Usually, it takes the form of upper management’s decision to “roll out” a change initiative to address a problem. For instance, employees might be complaining about something — work-life tensions, conflicts over cultural differences, and so forth. Rather than letting people take responsibility for addressing their problems — that is, get involved in coming up with a shared solution — management force-feeds the company a new program (B1 in “Shifting the Burden to Management”). This might reduce complaints for a time, and managers might even capture a few hearts and minds. But these gains won’t stick. Worse, this approach makes employees passive, as they come to depend more and more on management to solve their problems and “take care of them.” The more dependent they become, the less able they are to feel a sense of responsibility and get involved in grappling with their problems (R3 in the diagram).

This “sheep-dip” approach to change — standardized for the masses — completely ignores employees’ true potential for making their own decisions and managing their own issues. For example, consider the difference between a company that legislates rigid work hours and one that trusts its employees to pull an all-nighter when the work demands it—and to head out to spend time with their kids

SHIFTING THE BURDEN TO MANAGEMENT

on a Friday afternoon because the work is in good shape. People can’t learn how to make these kinds of judgments wisely for themselves if their employer treats them like children.

“Sheep dipping” has another consequence as well: Because it makes employees passive, it discourages the fluid transfer of knowledge that occurs when people feel involved in and responsible for their work. Instead of looking to one another, anticipating needs, and collaborating as a team, employees have their eyes on management, waiting to be taken care of. Knowledge remains trapped in individuals’ minds and in separate functions in the organization, and the firm never leverages its true potential.

From Control to Soul

So, if we can’t control complexity, how do we go to work every day with some semblance of our sanity? Should we just give up hoping that our organizations can navigate skillfully enough through the Badlands to survive the competition and maybe even achieve their vision? What are we to do if we can’t control our work, our employees, and our organization? How can we take our organizations to places they’ve never been — scary, dangerous places, but places that also hold out opportunities for unimagined achievement?

The answer lies in one word: soul. “Soul” is a funny word. It means different things to different people, and for some it has a strong spiritual element. But in the context we’re discussing now — organizational health, values, and change — its meaning has to do with entirely new, radical perspectives on work and life.

To cross the Badlands successfully, all of us — from senior executives to middle managers to individual contributors — need to adopt these “soulful” perspectives:

Understand the system; don’t control it. As we saw above, we can’t manage, manipulate, or avoid problems in our organizations without spawning some unintended — and often undesirable — consequences. Understanding the organizational and social systems we live and work in makes us far more able to work within those systems in a healthy, successful way.

Know the relationships in the system. Understanding a system means grasping the nature of the relationships among its parts — whether those parts are business functions, individuals, external forces acting on the organization, etc. By knowing how the parts all influence each other, we can avoid taking actions that ripple through the system in ways that we never intended.

Strengthen human relationships. Success doesn’t come from dead-on metrics or a seemingly bulletproof business model; it comes from one thing only: strong, positive relationships among human beings. When you really think about it, nothing good in the world happens until people get together, talk, understand one another’s perspectives and assumptions, and work together toward a compelling goal or a vision. Even the most brilliant individual working alone can achieve only so much without connecting and collaborating with other people.

Understand others’ perspectives. This can take guts. People’s mental models — their assumptions about how the world works — derive from a complicated process of having experiences, drawing conclusions from those experiences, and then approaching their lives from those premises. Understanding where another person is “coming from” means being able to set aside our own mental models and earn enough of that other person’s trust so that he or she feels comfortable sharing those unique perspectives.

Determine what we stand for. Why do you work, really? Forget the easy answers — “I want to make money” or “I want to buy a nice house.” What lies beneath those easy answers? Around the world, people work for the same handful of profound reasons: They want their lives to have meaning, they want to create something worthwhile and wonderful, they want to see their families thrive in safe surroundings, they want to contribute to their communities, they want to leave this Earth knowing that they made it better. All these reasons define what we stand for. By clarifying what we stand for — that is, knowing in our souls why we go to work every day — we learn that we all are striving for similar and important things. That realization alone can build community and commitment a lot faster than any “rolled-out” management initiative can.

Determine our trust and our trustworthiness. Strong relationships stem from bonds of trust between people. To trust others, we have to assume the best in them — until and unless they prove themselves otherwise. But equally important, we also need to ask ourselves how trustworthy we are. We must realize that others are looking to us to prove our trustworthiness as well. By carefully and slowly building mutual trust, we create a network of robust relationships that will support us as we move forward together.

Be humble, courageous, and vulnerable. Understanding ourselves and others in ways that strengthen our relationships takes enormous courage — and a major dose of humility. It also takes a willingness to say “I don’t know” at times — something that many companies certainly don’t encourage. And finally, it takes a willingness to make ourselves vulnerable — to explain to others why we think and act the way we do, and why we value the things we value.

Find “soul heroes.” We need to keep an eye out for people whom we sense we can learn from — people who live and embody these soulful perspectives. These individuals can be colleagues, family members, friends, customers, or neighbors. If we find someone like this at work — no matter what their position — we must not be afraid to approach them, to talk with them about these questions of values, trust, and soul.

Tools for Your Badlands Backpack

So, to venture into the Badlands, we need soul — whole new ways of looking at our lives and work. But soul alone won’t get us safely through to the other side. We wouldn’t approach the real Badlands without also bringing along a backpack filled with water, food, first-aid materials, and other tools for survival and comfort. Likewise, we shouldn’t tackle the Badlands of organizational complexity without the proper tools.

These five tools are especially crucial:

Systems Thinking Tools.The field of systems thinking provides some powerful devices for understanding the systems in which we live and work, and for communicating our understanding about those systems to the other people who inhabit them. Causal loop diagrams, like the one in “Shifting the Burden to Management,” let us graphically depict our assumptions about how the system works. When we build such a diagram with others, we especially enrich that understanding, because we pull all our isolated perspectives into one shared picture. From there, we can explore possible ways to work with the system to get the results we want. These diagrams also powerfully demonstrate the folly in trying to manhandle a system: When we draw them, we can better see the long-term, undesirable consequences of our attempts to control the system.

Dialogue. The field of dialogue has grown in recent years to include specific approaches to talking with one other. For example, dialogue emphasizes patience in exploring mutual understanding and in arriving at potential solutions to problems. It also encourages us to suspend our judgments about others during verbal exchanges — that is, to temporarily hold our judgments aside in order to grasp others’ reasons for acting or thinking as they do. Dialogue lets a group tap into its collective intelligence — a powerful way of transferring and leveraging knowledge.

Ladder of Inference. This tool offers a potent way to understand why we think and respond to our world as we do. It helps us see how we construct our mental models from our life experiences — and how those mental models can ossify if we don’t keep testing them to see whether they’re still relevant. In the workplace, we all make decisions, say things, and take actions based on our mental models. By using the Ladder of Inference to examine where those models came from, we can revise them as necessary — and reap much more shared understanding with colleagues. (For information about the Ladder of Inference, see The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook published by Currency/ Doubleday).

Scenario Planning. This field has also grown in recent years. Numerous organizations, notably Royal Dutch/Shell, have used scenario planning to remarkable effect. This tool reflects the fact that we can’t control systems. Scenario planning encourages us to instead imagine a broad array of possible futures for our organization or even our entire industry — and to make the best possible arrangements we can to prepare for and benefit from those potential outcomes. This approach thus acknowledges the complexities inherent in any system; after all, there’s no way to easily determine the many different directions a system’s impact may take.

Managing by Means. New methodologies are emerging that can help us assess the true costs of running our businesses — costs to human society, to the environment, and to the business itself. And costs in the short run as well as the long run. We must grapple with these methodologies if we hope to achieve the only long-term business goal that really makes sense: business that doesn’t destroy the very means on which it depends.

Traditional change management methods build things to stick. They do not build things to last and are thus ineffective because well-intentioned people create the strategy, solution, and problem sets based on a narrow set of assumptions. To create a sustainable organization, we must work to understand the complex system dynamics of the environment and experiment with multidimensional strategies. We must also work to understand diverse social dynamics and allow multiple perspectives and behaviors to emerge. Finally, we must trust ourselves, hold true to our core convictions, and have courage, humility, and soul. In these ways, we can navigate through — and even prosper in — the most desolate and challenging of Badlands.

David Berdish is the corporate governance manager at Ford Motor Company. He is leading the development of sustainable business principles that will integrate the “triple bottom line” of economics, environmental, and societal performance and global human-rights processes. He is also supporting the organizational learning efforts at the renovation of the historic Rouge Assembly site.

NEXT STEPS

- Talk with your family — your spouse and kids if you have them — about what you stand for, as individuals and as a family. Explore how you might better live those values.

- Have lunch with some people at work whom you admire. Talk with them about your organization’s challenges. Try creating simple causal diagrams together that depict your collective understanding about how a particular issue might arise at your firm.

- The next time you get into an uncomfortable misunderstanding with someone at home or at work, try to identify what experiences in your past may be causing you to respond in a particular way to the conflict. What might be making it hard for you to hear the other person?

- During a conflict, also try setting aside any judgments you have about the other person. Instead, try hard to listen to where that person is coming from.

- While discussing projects with a team at work, brainstorm the kinds of unexpected costs or effects that the project might have. Really cast your net wide; visualize the product making its way through production, distribution, use — and disposal. What impact does it exert, on whom and what, at each of these stages?