Take a moment to put on a new set of glasses. Change your perspective.

Consider, for a moment, that the most widespread and pervasive learning in your organization may not be happening in training rooms, conference rooms, or boardrooms, but in the cafeteria, the hallways, and the cafe across the street. Imagine that through e-mail exchanges, phone visits, and bull sessions with colleagues, people at all levels of the organization are sharing critical business knowledge, exploring underlying assumptions, and creating innovative solutions to key business issues.

Imagine that “the grapevine” is not a poisonous plant to be cut off at the roots, but a natural source of vitality to be cultivated and nourished. Imagine that its branching, intertwining shoots are the natural pathways through which information and energy flow in the organization.

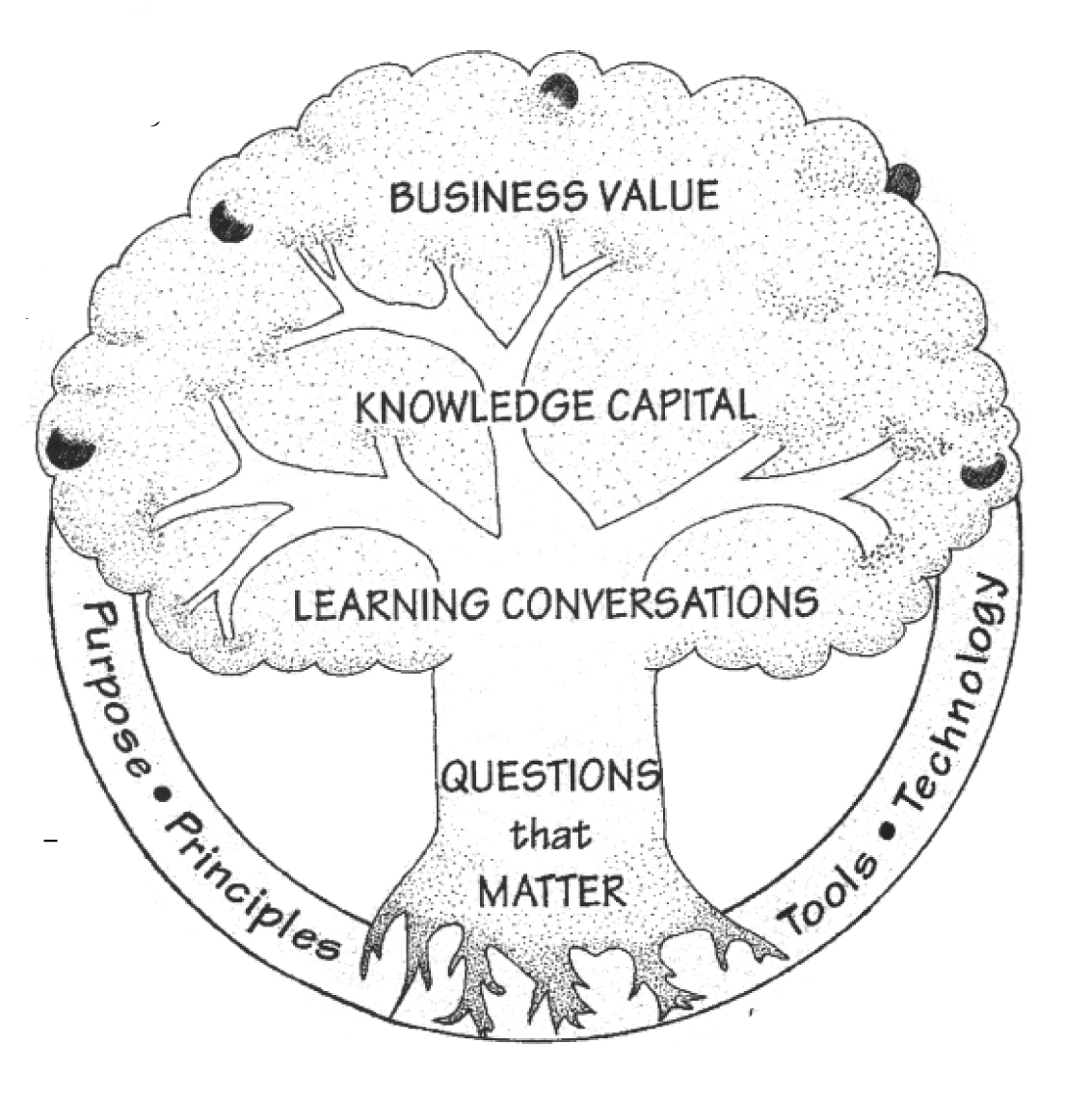

Consider that these informal networks of learning conversations are as much a core business process as marketing, distribution, or product development. In fact, thoughtful conversations around questions that matter might be the core process in any company — the source of organizational intelligence that enables the other business processes to create positive results. A more strategic approach to this core process can not only appreciate an organization’s intellectual capital, but can also create sustainable business value in the knowledge economy.

The Power of Conversation

All of us have, at one time or another, experienced a conversation that has had a powerful impact on us — one that sparked a new insight or helped us see a problem in a radically different light. What sets apart this type of generative, transformative conversation from the many exchanges that occur on a daily basis at our workplaces and in our homes? What are the qualities that make it worthwhile?

We have posed this question to hundreds of executives and employees in diverse cultures around the globe. While we have seen a wide range of individual experiences, common themes include:

- There was a sense of mutual respect between us.

- We took the time to really talk together and reflect about what we each thought was important.

- We listened to each other, even if there were differences.

- I was accepted and not judged by the others in the conversation.

- The conversation helped strengthen our relationship.

- We explored questions that mattered.

- We developed shared meaning that wasn’t there when we began.

- I learned something new or important.

- It strengthened our mutual commitment.

When we consider the power of conversation to generate new insight or committed action, its importance in our work lives is quite obvious. Fernando Flores, one of the first to highlight this crucial link has said that “an organization’s results are determined through webs of human commitments, born in webs of human conversations. ”We share a common heritage as fundamentally social beings who, together in conversation, organize for action and create a common future.

Yet this view of conversation as a way of organizing action contradicts a basic tenet in many organizational cultures — one based on the edict, “stop talking and get to work!” The underlying belief is that conversation takes time away from the more “important” work of the organization (see “Discovering Your Organization’s Capabilities”).

Paradoxically, what we are discovering is that the talking — the network of conversations — actually catalyzes action. Through conversation we discover who cares about what, and who will take accountability for next steps. It is the means through which requests are initiated and commitments made. From this perspective, a more useful operating principle for organizational life might be “start talking and get to work!”

Discovering Communities of Practice

Etienne Wenger and his colleagues at the Institute for Research on Learning (IRL), an outgrowth of Xerox’s pioneering Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), confirmed the centrality of collaborative conversation when they studied how learning actually takes place in an organization. Using interdisciplinary teams of anthropologists, sociologists, cognitive scientists, and technology specialists, IRL has found that knowledge creation is primarily a social rather than an individual process. People learn together in conversation as they work and practice together. Therefore, important innovations are constantly being created at the grass-roots level, on the periphery, and at the local level, as people share common questions and concerns.

“Communities of practice” is what IRL calls the foundation for this social process of learning. In our own large-systems change work, we have called them “work communities.” These self-organizing networks are formed naturally by people engaged in a common enterprise — people who are learning together through the practice of their real work.

DISCOVERING YOUR ORGANIZATION’S CAPABILITIES

How well does your company appreciate the value of conversation as a core business practice? Consider the following questions:

- Does your organization consider conversation to be the heart of the “real work” of knowledge creation and of building intellectual capital?

- How often do the members of your organization focus on the principles and practices of good conversation as they engage with colleagues, customers, or suppliers?

- Do you consider one of your primary roles to serve as a convener or host for good conversations about questions that matter?

- How much time do you and your colleagues spend discovering the right questions in relation to the time spent finding the right answers?

- What enabling process tools or process disciplines have you seen being used systematically to support good conversations?

- Is your physical work space or office area designed to encourage the informal interactions that support good conversation and effective learning?

- Do you have technology systems and professional resources devoted to harvesting the knowledge being cultivated at the grass roots level and making it accessible to others across the organization?

- How much of your training and development budget is devoted to supporting informal learning conversations and sharing effective practices across organizational boundaries?

Conversation as a Core Process

IRL has found that the knowledge embodied in these communities is usually shared and developed through ongoing conversations. Because of this, John Seeley Brown, chief scientist at Xerox PARC, sees a critical need to develop systems and processes that “help foster new and useful kinds of conversations in the workplace.”

The MIT Center for Organizational Learning (OLC) has also been pursuing this challenge through ongoing research into the role of conversation in business settings. For several years, the study and practice of dialogue — a process of collective thinking and generative learning based on the seminal work of David Bohm — has been a central part of the Center’s action research and training efforts. In collaboration with the OLC, we are now developing principles and practices to support strategic conversation as a key business leverage.

In addition, Peter and Trudy Johnson-Lenz, innovators in the field of “groupware” technologies, have initiated a multi-company Community of Inquiry and Practice focused on supporting coherent conversations in cyberspace. Group members are actively experimenting with ways of strengthening the conversational practices of on-line communities, including the use of formal dialogue and inquiry mapping. Underlying all these activities is the belief that collaborative conversation is a strategic asset for supporting organizational learning infra-structures.

Alan Webber, in his pioneering Harvard Business Review article “What’s So New About the New Economy,” goes one step further and asserts that conversation is the lifeblood of the knowledge economy. Where information is the raw material and ideas are the currency of exchange, he explains, good conversations become the crucible in which knowledge workers to share and refine their thinking in order to create value-added products and services. In his assessment, “The most important work in the knowledge economy is conversation.”

Tools and Technologies That Support Good Conversation

Given that many organizations still operate from a “stop talking and get to work” mentality, it will take some focused attention to create an environment that recognizes and supports conversation as a core process. Toward this end, many companies are beginning to experiment with collaborative technologies and process tools that encourage the development of knowledge capital.

For example, one major consumer products company has instituted an innovative planning process throughout its sales organization. The process begins with an extensive situation analysis, in which management and field personnel explore all facets of the current business and competitive environment. From this analysis, they frame several core questions that will guide their subsequent strategic conversations. By encouraging the sales staff to develop a more disciplined focus on asking essential questions, the organization is encouraging the use of an inquiry model for business planning.

Other companies are exploring ways to create physical environments that encourage knowledge-generating conversations. For example, Steelcase Corporation has created office areas designed as “neighborhoods” where product and business teams work together in close proximity. Adjacent to these office neighborhoods are community “commons,” where informal conversation and community interaction occur. In similar style, SAS Airlines in Stockholm has a “central plaza” in the midst of its corporate headquarters. The plaza contains shops and a cafe where people from all levels and functions are encouraged to visit and share ideas.

Other organizations are developing sophisticated tools for collaborative work. For example, Buckman Laboratories International has created a worldwide intranet that enables its global sales force in 90 countries to engage in ongoing conversations about meeting customer needs. Users can contribute to the conversations at any time, from any place, and in several different languages. The system automatically updates the evolving “knowledge threads” as questions are explored and answers discovered.

With a simple and consistent focus on questions that matter, casual conversations are transformed into collective inquiry.

Likewise, Xerox is experimenting with Jupiter, a “virtual social reality” computer system that its designers hope will “support the organizational mind.” Jupiter comes complete with virtual white boards, personal offices, meeting rooms, and “lounges” where members can take a break and bump into a friend from a completely different city. In this environment, people can participate in larger community conversations as well as work in small groups on specific projects. Michael Schrage, in his book Shared Minds, points out that such collaborative tools and techniques “will transform both the perception and reality of conversation, collaboration, innovation, and creativity.”

Questions That Matter

Developing processes and infrastructure for tapping into the collective intelligence in an organization is an important part of establishing conversation as a core business process. But one area of activity that is just as crucial is honing the skill of discovering and exploring questions that matter. Why? Because the quality of our learning process depends on the quality of the questions we ask. Clear, bold, and penetrating questions that elicit a full range of responses tend to open the social context for learning. People engaged in the conversation develop a common concern for deeper levels of shared meaning.

Focusing on essential questions enables us to challenge our underlying assumptions in constructive ways. With a simple and consistent focus on questions that matter, casual conversations are transformed into collective inquiry. As these questions “travel” throughout the system, they enable creative solutions to emerge in unexpected ways.

Leading Inquiring Systems

What skills, knowledge, and personal qualities will be required in the more collaborative, networked organizations of the future? What are the emerging leadership capabilities that will foster the evolution of inquiring systems— systems that strengthen their capacity to learn, adapt, and create long-term business and social value? We believe there are several capabilities that will be essential to this process.

Framing Strategic Questions. Ray Kroc, the founder of McDonald’s, launched that company to its preeminent market position by posing a simple but powerful question to his colleagues: “How can we assure a consistent hamburger for people who are traveling on the road?”

Mastering the art and architecture of framing powerful questions that inspire strategic dialogue and committed action will be a critical leadership skill. Strategic questions create dissonance between current experiences and beliefs while evoking new possibilities for collective discovery. But they also serve as the glue that holds together overlapping webs of conversations in which diverse resources combine and recombine to create innovative solutions and business value.

Convening Learning Conversations. As another core aspect of this new work, leaders will create multiple opportunities for learning conversations. However, authentic conversation is less likely to occur in a climate of fear, mistrust, and hierarchical control. The human mind and heart must be fully engaged in authentic conversation for new knowledge to be built.

Thus, the ability to facilitate working conversations that enhance trust and reduce fear will become an important leadership capability. To succeed in this pursuit, leaders will need to strengthen their skills in the use of dialogue and other approaches that deepen collective inquiry (see “Improving the Quality of Learning Conversations”).

These skills include:

- Creating a climate of discovery;

- Suspending premature judgment;

- Exploring underlying assumptions and beliefs;

- Listening for connections between ideas;

- Honoring diverse perspectives; and

- Articulating shared understanding.

In this process, the authenticity, integrity, and personal values of leaders will become central to their role as “conveners and connectors”—of both people and ideas. Strengthening personal relationships through networks of collaborative conversations will be essential for building intellectual capital.

IMPROVING THE QUALITY OF LEARNING CONVERSATIONS

A number of companies are experimenting with simple process innovations that can have an immediate impact on the quality of conversation throughout an organization. Here are some suggestions from their work:

Remember “good conversations.” Ask people who are working together on a project to remember a time in their lives when they had a really good conversation and what made it memorable. People already know how to have good conversations where mutual respect, care-full listening, collective insight, and innovation occur. By remembering what they already know, people are more able to bring these qualities into their ongoing work relationships.

Find the right setting. Most workplaces are not conducive to good conversations. Consider the typical conference room or board room. Sterile. Cold. Impersonal. Fluorescent lights. Human beings were not designed to think together creatively in places such as these. Consider creating or using informal living room settings, with comfortable seating. Provide food. Find spots that have natural light. Create a hospitable environment for people to function socially as well as conceptually. Convene small work sessions in a quiet cafe. Shift your perspective to one of “hosting a gathering” rather than “chairing a meeting.”

Create shared space. People more easily discover shared meaning in conversation when they can, literally, see what you mean. That is why people often scribble on napkins, use white boards, or doodle when they are working together — so they can clarify their thinking. Creating space where visual images or common data can be explored together is often the key to producing breakthrough thinking.

Slow down to speed up. It is difficult to think together when everyone jumps into the conversation at breakneck speed. A number of corporations today are experimenting with the “talking stick,” a process tool which has been in continuous use for thousands of years in Native American and other indigenous cultures. As the talking stick (or any other small object) is passed to each member, he or she each has an opportunity to share the essential question or core meaning that is emerging for them in the conversation. The passing of this small object in a respectful way enables each voice to be heard and ensures a quality of attention and listening that might not otherwise be available.

Honor unique contributions. Underneath it all, people are naturally curious, especially about things they care about. Encourage those who are in the conversation to share why the exploration matters to them and how they can contribute to each other’s learning. Create a symbolic “gift exchange,” where people offer their diverse points of view as unique contributions to the common journey.

See reflection as action. Just as we are now seeing conversation as work, we can begin to discover reflection as action. Reflection enables new meanings to be seen and shared, allows learning to be noticed and integrated, and enables the “questions that matter” to surface. Some organizations are using a process of “time ins” rather than “time outs” during key conversations to discuss “learnings and churnings.” They look at what has been discovered and at each person’s deeper questions as the work goes forward.

Supporting Appreciative Inquiry.

Becoming open to the multiple possibilities that conversations create will require a shift in leadership orientation from focusing on what is not working and how to fix it, to discovering and appreciating what is working and how to leverage it. Appreciative inquiry was developed by David Cooperrider and his colleagues at Case Western University as a powerful business process for valuing previously untapped sources of knowledge, vitality, and energy. When used in a disciplined way, this type of inquiry stimulates lively conversations about fundamental organizational values, and uncovers hidden assets that create sustainable business and social value.

Shifting the focus in this direction enables leaders to foster networks of conversations focused on leveraging emerging possibilities rather than just on fixing past mistakes. This attitude creates a “generative field” of mutual trust and appreciation, in which groups feel encouraged to discover and share their unique contributions in order to build their collective intellectual capital.

Fostering Shared Meaning. As organizations enter the 21st century, leaders will discover that one of their unique contributions is to provide “conceptual leadership” — creating a larger context within which groups can deepen or shift their thinking together.

To build shared context, we must first understand the importance of language for shaping our thought. We make meaning of our experiences through stories, images, and metaphors. To tap into this pool of shared meaning, leaders need to put time and attention into framing common language and developing shared images and metaphors. This can be done by constructing compelling scenarios — “stories of the future” that provide shared meaning and collective purpose across organization boundaries. In addition, it is important to incorporate time for system-wide reflection, to enable the collective “sense-making” that is essential in times of turbulence and change.

Nurturing Communities of Practice. Much of the learning and knowledge creation in an organization happens through informal relationships. But few of today’s executives and strategists have been trained to notice and honor the social fabric of informal “communities of practice.”

Nurturing and sustaining these learning communities will be another core aspect of the leader’s new work. Principles of community organization — including recruiting volunteers, convening gatherings, developing partnerships, and hosting celebrations — will be essential to this practice. Finally, the existing communities of practice need to be taken into account when reengineering work processes, so new work flows do not destroy the collective knowledge that is woven into them.

Using Collaborative Technologies. The notion of personal computing is fast giving way to “interpersonal computing.” New collaborative technologies create possibilities for different kinds of conversations. People can “see” innovative ideas pop up on their computer screen or on large wall murals created by graphics specialists. Such multisensory, interactive conversations enable people to share their thoughts and create knowledge in ways that have rarely been possible before.

As these tools become more widely available, the notion of “leadership” will expand to include facilitating on-line conversations and supporting the design of integrated learning systems that enable the co-creation of products and services among widely distributed work groups.

Creating the Future

Where collaborative learning and breakthrough thinking are requirements for a sustainable business future, the development of appropriate tool and environments to support good conversations are also essential. Indeed, it is the network and nature of those conversations that will help determine the organization’s strategic capacity to create the future it wants, rather than being forced to live with the future it gets.

Seeing the systemic ways in which conversation helps a learning organization evolve, and utilizing process principles, tools, and technologies to support this evolution, are everyone’s responsibilities. For only in this way can organizations cultivate both the knowledge required to thrive today and the wisdom needed to ensure a sustainable future.

Juanita Brown and David Isaacs (Mill Valley, CA) are also senior affiliates at the MIT Center for Organizational Learning. They serve as strategists and thinking partners with senior leaders, applying living systems principles to the evolution of knowledge-based organizations and large-scale change initiatives.

The authors would like to thank the Intellectual Capital Pioneers Group as well as Jennifer Landau and Susan Kelly of Whole Systems Associates for contributions to the development of their recent thinking.

Editorial support for this article was provided by Sue Wetzler of Whole Systems Associates and Colleen Lannon of Pegasus Communications.