As we seek ways to cope with the increasing rate and complexity of change affecting our businesses, many of us have begun to recognize the need for ongoing transformation of our organizations through experimentation and learning. Yet we’re finding that making the changes necessary to support this process can be difficult. Adopting new ways of working together can prove extremely challenging. And lessons we’ve learned from past experiences may not directly apply to those we are facing now. To overcome these obstacles, many of us turn to consultants with expertise in the area of change management.

But how do we go about finding a consultant who can give us the help we need? Managers—particularly those seeking to build “learning organizations” — can find themselves frustrated by the quality of advice and services they receive from outside experts. Recent research into the experience of consultants who specialize in organizational learning disciplines suggests that this frustration can stem from the conflicting, unspoken assumptions managers and consultants hold as they embark on an initiative together.

This finding raises important questions for managers: What mental models do you hold about the change process? What role should consultants play? How do your preconceptions shape the relationships you form with consultants? And, finally, what outcomes do you expect — quick fixes or lasting shifts in corporate culture?

To begin to explore these questions, let’s first consider why tackling today’s complex challenges requires a shift in understanding about learning and work. We then examine the role of the consultant in building capacity for ongoing organizational learning.

Building Social Bonds

Thought leaders such as Peter Senge and William Isaacs suggest that many managers fail to bring about needed organizational change because of their assumptions about learning and work. For example, many executives assume that work is best done by finding a technically competent person in the area of concern, having this person determine the most appropriate course of action, and then implementing that action. From this perspective, learning is a process through which individuals gain technical knowledge.

These executives also assume that the best way to determine technical ability is through competition — that is, generating a debate between technical experts to determine who best understands how to help. Feeling the need to be proactive, these specialists may hastily label something as a “problem” and look for the most direct solution: the “quickest fix.” This approach often improves the situation in the short run but actually worsens it over the long term.

Learning experts suggest that this emphasis on technical competence and competition may be useful for relatively simple issues, but not for more complex challenges. The difficulties facing most managers today are generally too intricate for one or two people to determine the right course of action based on previous experience. Each situation is likely to be different from previous ones, requiring solutions tailored to the particular circumstances.

Therefore, rather than focusing on individual expertise, Senge and others recommend a view of work that emphasizes building social bonds — through practicing collaborative tools, such as dialogue, partnership coaching, and visioning — while getting things done. As people develop new skills for conversing and new ways of behaving, they build strong relationships and increase their capacity for anticipating and handling novel situations together. From this perspective, learning means building the capacity to learn together how to meet future challenges.

From Problem Solving to Capacity Building

Thus, to be successful in this rapidly changing marketplace, we need to cultivate groups of people with diverse perspectives who can learn how to come to a shared understanding of the often hidden forces that shape their organizations both internally and externally. In addition, these teams should include those charged with implementing decisions. As a result, they can take more effective action at a fundamental rather than symptomatic level.

In this context, according to Senge and Daniel H. Kim, consultants are ideally capacity builders who develop links between research and practice rather than problem solvers. They provide methods and tools to help others expand their capabilities and skills on an ongoing basis, thereby transforming concepts into practical know-how and results. These consultants may have knowledge in a variety of areas, but the contribution they make is framed as building capacity for learning and interpersonal connections rather than providing expertise.

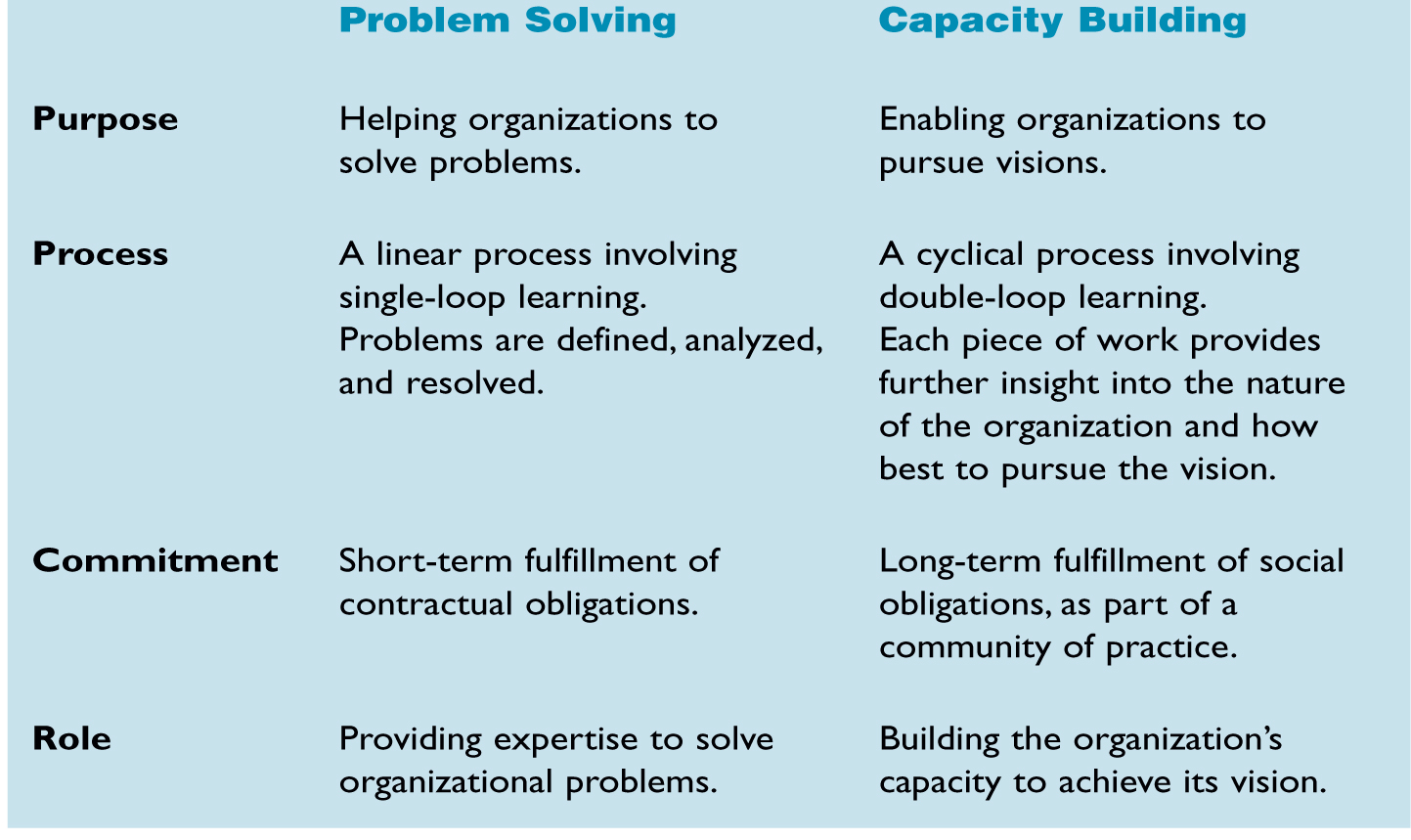

What are the main differences between a problem-solving versus a capacity-building approach to consulting? (See “Alternative Models of Consulting.”)

Linear vs. Cyclical Processes. Consultants who take a problem-solving orientation typically use a linear process in their work. They first identify problems, then diagnose them, and finally find and implement solutions. At this point, the project or consulting assignment often ends. In contrast, consultants who view their purpose as enabling organizations to continually adjust to change typically implement a cyclical process. With each project or assignment, they generate new information about the organization’s culture and what is required for it to move toward its vision.

Single vs. Double-Loop Learning. Chris Argyris and Donald Schön were the first to describe single-loop and double-loop learning. When we engage in single-loop learning, as is typical of a problem-solving approach, we take action to solve a problem, assess the consequences of our intervention, and use what we learn in taking new actions; we continue this process until we think we have solved the problem. Single-loop learning might involve asking, “Did the action solve the problem? Did we meet the standards we had set?”

In double-loop learning, which is a key element of building capacity to handle change, we assess not only the effect of our actions on the problem, but also the variables that shape thinking within the organization more broadly. We do this by asking questions such as, “What made us think this was a problem? Why did we set the standards in such a way?”

Finite Commitment vs. “Communities of Practice.” Consultants who employ a linear process that has definite starting and finishing points usually view the client relationship as temporary, ending when the contract is fulfilled. Those focused on building capacity using a cyclical approach may utilize contracts to define work they do, but they view their purpose, process, and commitment as long term.

Etienne Wenger has referred to the long-term relationship that can form between a consultant and client organization as a “community of practice” (see “Communities of Practice: Learning As a Social System,” V9N5). While not formally part of the organization, consultants learn together with organization members through their regular interactions. As a result, they create social bonds and a shared repertoire of resources (common language, sensibilities, and so forth) that enable them to collaborate effectively.

ALTERNATIVE MODELS OF CONSULTING

These communities of practice do not expire when a contract ends or a project is completed. Rather, the nature of the community shifts from active engagement to “dispersed,” where members keep in touch though they no longer engage with the same intensity. In this situation, consultants feel committed to organizations beyond the life of particular contracts, because they feel they belong to a community. They might, without charging a fee, provide advice outside of a given project.

Experts vs. Capacity Builders. Finally, the role the consultant plays differs according to his or her orientation and the client’s expectations. In a problem-solving approach, a client would expect a consultant to act as an expert in the managers’ area of need. This role might include helping managers determine what they need to do or helping managers who already know what they want to do to implement their plans. On the other hand, clients who understand the power of building capacity for learning may require a consultant to facilitate the process by which members of the organization solve their own problems.

The problem-solving and capacity-building approaches appear to be quite separate models of how consultants can act. We might expect that consultants would consistently adopt one or the other of the approaches. Our research suggests, however, that consultants’ choices are more complex and have a lot to do with their clients’ assumptions about how to tackle the organizational challenges they face.

Handling the Tension

Although many consultants may agree with the philosophy of organizational learning, because they practice predominantly among clients oriented toward solving problems, they feel pulled between the two models. To begin to explore the impact of this tension on client-consultant relationships, we interviewed seven New Zealand consultants who had worked, cumulatively, with organizations in four of the five disciplines that Senge says are essential to organizational learning: team learning, shared vision, systems thinking, and personal mastery. All worked independently or in firms with 10 or fewer associates. Four were founders and managers of their own consulting companies. Only one consultant from any given company was represented in the study. All were either known to the researchers or recommended by one of the other consultants being interviewed.

We chose these consultants because we knew they preferred taking a capacity-building approach in their work and wanted to analyze how they dealt with the tension between the short-term results that some clients wanted them to produce and their personal desire to help the client support the creation of infrastructures for learning. We kept the sample small so we could conduct semi-structured interviews to generate rich descriptions of consulting practices. Such descriptions allowed us to explore the particular issues relevant to consultants as they dealt with the tension between problem solving and capacity building.

We asked the consultants to discuss how they had carried out critical phases of the consulting process with what they considered a particularly important client. They described how they had gained access to the organization, established a contract, collected data, diagnosed needs, implemented solutions, reviewed work, and terminated the consultancy. We also asked them how the relationship with the chosen client differed from relationships with other clients.

THEMES FROM INTERVIEWS

Consulting Practice Based on Capacity Building

- Use of reflection

- Use of conversation as a strategic practice

- Emphasis on attitudinal change and “knowledge transfer” as benefits to clients

Factors Limiting Capacity Building

- Clients’ fear of an “overly theoretical” approach

- Lack of trust in the relationship

Consulting for Capacity Building. After we analyzed transcripts of the interviews, we saw clear evidence that the consultants viewed their work in terms of building capacity. The consultants’ descriptions of actions they took revealed their deliberate efforts to conduct themselves in ways that aligned with organizational learning philosophies (see “Themes from Interviews”). For instance, they sought to understand their clients’ work at a deep level and confront clients with double-loop challenges that went beyond contractual obligations.

In addition, the consultants described the kinds of benefits their clients received in behavioral terms, that is, they didn’t discuss how they solved particular problems, but rather described their clients’ attitudinal changes with phrases such as “greater self-awareness,” “commitment to people issues,” “improved communications,” and “a shift from a managing or controlling orientation to a learning orientation.” One consultant described the benefits in this way:

“I am helping them to work as a team rather than as individuals. So they are benefiting . . . partly from my intellectual input and partly from my facilitation skills, and also from my ability to challenge them. They end up better organized, more focused, thinking slightly differently — sometimes a lot differently — which in the beginning they couldn’t. Generally speaking, they believe they have done it themselves, which is about right because they have developed themselves. The thinking is theirs. The decision is theirs.”

Three participants also mentioned “knowledge transfer to the client” as an important outcome; they didn’t just teach their clients technical “know-how.” One participant described his goal as passing his “cast of mind” or way of thinking about the work to his client. Another said, “One of the requirements of the design is that [clients] are able to perform some of the skills we perform for them and then [the skills] become embedded. So we demonstrate over and over again. . . . Otherwise there is no change in behavior. They have to unlearn 30 years of belief and practice, and I know how difficult that is. But as the project draws down, we will appear less frequently.”

Along with framing benefits to clients in capacity-building terms, participants spoke about adopting organizational learning principles directly into their own practice. For example, three consultants described how they incorporated reflection into their process of review, both with the client and with themselves. One respondent felt that personal reflection was often a more intense form of review than client feedback because “My experience is we tend to be harder on ourselves than clients [are].”

Four participants considered ongoing conversations with their clients — what Juanita Brown and David Isaacs describe as a core business process that contributes to learning — an essential part of their consulting work. Talk in organizations is often focused on making decisions, which in turn creates adversarial relationships that do not encourage reflection or shared understanding. Conversation needs to allow for a full range of contributions — offering new ideas, yielding to the direction of others, and reflecting in silence — to create the conditions for learning.

Some described using conversation not only to establish issues to address but to build commitment to the change processes being considered. One participant said that conversation often replaced the traditional attempts by managers to “sell” change programs to the rest of the organization. Engaging people throughout the organization in conversation about issues of significant concern allowed shared understanding of needed action to emerge.

Limits to Capacity Building. As this study indicates, consultants endeavored to incorporate capacity building into their work with key clients with whom they had longstanding relationships. However, two outcomes from the interviews showed that this approach was not possible in all their projects.

Six participants mentioned clients’ apprehension about taking an overly theoretical orientation, a fear intensified by the fact that some areas of organizational learning — such as systems thinking and reflective conversation — may feel “unnatural” and involve concepts that do not appear to have immediate practical value to the client. One participant described clients struggling to “find the connection between what we are talking about and the bottom line.” To respond to such concerns, these consultants deliberately developed strategies that both delivered practical outcomes and challenged clients to “widen their mindsets.” Often this involved starting the relationship with intermittent contacts and small projects, which built into long-term relationships over time.

Six participants also mentioned the importance of developing trust with the clients before the capacity building work could take hold. Because practicing organizational learning concepts requires the involvement of both minds and hearts, along with deeper levels of communication, consultants reported feeling bolder in confronting clients about issues that needed to be addressed only as trust grew. As one participant put it: “With a stronger relationship with the client . . . I became bolder . . . not letting them ‘wimp out,’ and I would say, ‘Give it a go.’” Another expressed the tendency for consultants to demonstrate personal commitment as they tried to build trust and capacity: “We can’t retreat in the end and say, ‘You paid us to do this thing.’ So we tend to enter into quite deep relationships with clients because of this. The communication modes and the levels of trust are high and we are working with minds and hearts. When we are doing learning, there is no other way.”

Implications for Consultants and Managers

Although this research was exploratory, involving interviews with a small sample of consultants, the results were enlightening to both the interviewers and participants. We had suspected that consultants would have an “either/or” approach to resolving the tension inherent in their position. Either they would operate according to traditional models of consulting, with an emphasis on technical rationality, or they would adapt their practice to reflect organizational learning principles.

We were surprised and encouraged to find that the consultants interviewed had more sophisticated ways of dealing with the paradox. They were able to hold building capacity for learning as an ideal, yet work with clients who did not allow them to put this philosophy into practice. They typically started their relationships with projects aimed at deliverable outcomes that allowed them to establish credibility. Consultants were willing to establish expertise by finding practical solutions to the client’s immediate business problems. At the same time, the participants in this study consciously built relationships with clients that would make capacity-building consulting possible in the future.

Consultants reported being able to do their best work within trusting relationships with clients. Such relationships enabled them:

- To more effectively understand clients’ real needs through deeper insights into the organization.

- To be bolder in confronting clients with fundamental changes that needed to be made.

- To review and improve their own practice openly and collaboratively with clients.

Participants also generally talked about their own responsibility in building trusting relationships. They described strategies such as using small, intermittent projects with clear, practical outcomes and deliberately avoiding language and work that appeared too theoretical or conceptual.

Although the focus of the research was on consultants, this finding has important implications for managers seeking to use consulting services. Because the responsibility for the development and maintenance of any relationship lies with both parties, managers need to understand how to enable consultants to be most effective. In situations where managers do not accept this responsibility, a Catch-22 situation seems likely to occur. For example, managers may hire consultants to build the organization’s capacity for learning, but reward only those who provide short-term, expert solutions to organizational problems. In doing so, they force consultants to compete with each other and offer them little freedom to experiment, act openly, or confront real issues.

While all the consultants in the study reported being able to form successful long-term relationships with some managers, they also cited many examples where executives’ assumptions made it difficult to do so (see “Mike’s Story”). For these consultants, the majority of their clients were primarily interested in having their problems solved.

MIKE'S STORY

I now start a relationship by asking clients, “What legacy do you want to leave behind? How can I help you create that legacy? How do we sustain this legacy?” I don’t work without the commitment of the CEO. And I ask CEOs about their commitment. I ask, “What role are you going to play?” and “Tell me about your track record in sponsoring long-term change.”

When I run leadership programs, I now include a two-year “Sustain” component, where I stay in touch with regular e-mails and newsletters and provide people with ongoing mentoring support.

What challenge does this research hold for you? If you want to lead change in your organization with the help of consultants, you must build trusting partnerships that will allow the consultants to act in a truly capacity-building role. While doing so is based on a set of assumptions that may feel unfamiliar and unnatural to many managers, those who can make this shift in perspective will have an advantage in their efforts to build organizations equipped to adapt to the challenges of the future.

Phil Ramsey (P. L. Ramsey@massey.ac.nz) is a lecturer in human resource development at Massey University in New Zealand.

Paresha Sinha has consulted and taught in India. Her master’s degree included research on consulting for learning organizations. Paresha currently works for the Centre for the Study of Leadership at Victoria University, New Zealand.

For Further Reading

Brown, Juanita, and David Isaacs. “Conversation As a Core Business Process,” The Systems Thinker, V7N10, December 1996/January 1997

Organizational Learning at Work: Embracing the Challenges of the New Workplace (Pegasus Communications, 1999)

Tannen, Deborah. The Argument Culture: Moving from Debate to Dialogue (Random House, 1998)

NEXT STEPS

- With your team, discuss consultants with whom you have worked. Aim to:

- Build your sensitivity to capacity-building and problem-solving orientations;

- Identify where developing a longterm relationship would be appropriate.

- Review your processes for concluding consulting projects. How can you incorporate double-loop inquiry based around consultants’ insights?

- Talk with preferred consultants about what it would take for them to feel free to do their best work.