Recently, I had a long conversation with my fifteen-year-old daughter, Elise, about why she had to learn algebra. I had helped her with a complex problem that neither one of us could understand at first. After much consternation, frustration, and finally relief, Elise stumbled upon a related concept that helped her solve the problem at hand. Then she asked, “Do you ever use algebra now that you are an adult?”, “No, not the complex type of problems we were just working on,” I admitted. “Then why do I have to learn this stuff, if I’ll never use it again?” she implored., “It’s not useful!”

This exchange brings into sharp contrast the two different definitions of learning that we were operating under. For Elise, learning algebra meant acquiring information in her head about how to manipulate numbers and symbols according to prescribed rules in order to give an answer that would be deemed correct by someone in authority. My definition of learning, in contrast, involved increasing the ability to achieve desired results. Learning had to be practically useful — it had to lead to outcomes in the real world. To me, what Elise was doing wasn’t learning at all: She was simply storing information that she may or may not ever retrieve again (she has no interest in pursuing a career in math or science). So if what she was doing really wasn’t learning, why did I want her to learn algebra? For a while, I really wasn’t quite sure. How was studying algebra going to help Elise achieve her desired results?

TEAM TIP

Becoming a learner is difficult to do in isolation from other people. Partner with others to develop your “learning muscles” by implementing practices in each of the five disciplines — personal mastery, shared vision, mental models, systems thinking, and team learning.

In a moment of inspired brilliance (or so I thought), I conjured up three reasons why she should learn algebra: (1) It increases brain development by making new neural connections; (2) It helps her acquire intellectual discipline; and (3) It increases her maturity. She was having a hard time relating to these noble, idealized reasons. Then as an afterthought, I added a fourth: It helps her do better on her college entrance exams. Now, I had her attention. She saw a practical use for algebra after all.

As the story above illustrates, we need a more robust perspective of learning than we’ve had in the past. In this article, I am advocating for an integrated framework that describes a new way to understand, utilize, and sustain learning—and, in turn, achieve our desired results.

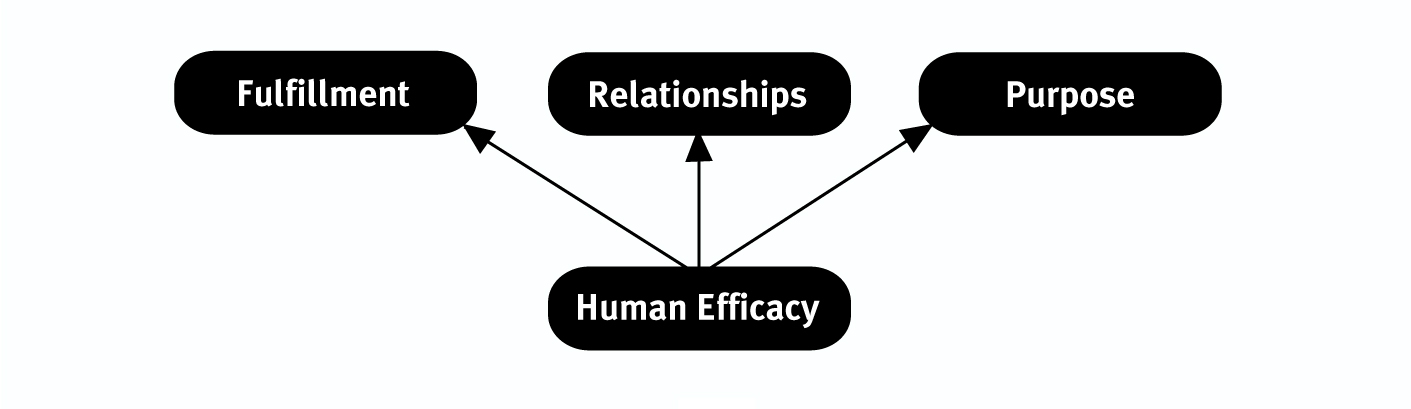

Human Efficacy

The ultimate aim of humans can be boiled down into three basic categories:

- Seeking fulfillment (pursuing happiness, consciousness, meaning)

- Creating relationships (giving and receiving love, strengthening connection to other people or a higher being)

- Having a purpose (pursuing a dream, fighting for justice, improving the world)

We cannot achieve these aims or our day-to-day goals (e.g., shaving, buying groceries, getting your kids to school on time, serving people in need) without a certain level of human efficacy.

Efficacy is being able to produce a desired effect (see “Achieving Results and Human Efficacy”). Some level of effort must be expended, and therefore some effect produced, to attain our goals as humans. (This is not to say that we can achieve all our aims through individual human effort alone. We must work in cooperation with others and in alignment with our sources of influence, authority, or wisdom. However, we cannot fail to exert an effort and expect we are going to get the outcome we’re seeking.)

ACHIEVING RESULTS AND HUMAN EFFICACY

For example, let’s say you want to experience more love in your life. How successful would you be if, in order to accomplish this goal, you sit in a chair and wait for the love to come to you? You don’t talk to anyone, you don’t look at anyone, you don’t think about anyone — in reality, all you really do is wait. Not very. You will be unable to produce the desired effect. Another example: Will it be possible for you to be more effective in your job if you don’t initiate some sort of movement or influence — even if that movement is simply to begin to notice what others are saying or doing? All desires, lofty or modest, will only be reached through some level of human efficacy.

So then, how do you increase your efficacy? Psychologist Albert Bandura argues that there are several sources for increasing our effectiveness: “They include [1] mastery experiences, [2] seeing people similar to oneself manage task demands successfully, [3] social persuasion that one has the capabilities to succeed in given activities, and [4] inferences from somatic and emotional states indicative of personal strengths and vulnerabilities.” Bandura goes on to say that “the most effective way of creating a strong sense of efficacy is through mastery experiences” (Albert Bandura, “Self-Efficacy,” in Encyclopedia of Human Behavior). In other words, you build efficacy by repeatedly achieving your desired results.

The next question, naturally, is, “How do you get better at ‘repeatedly achieving your desired results’?” The answer is learning. Unfortunately, without understanding how learning actually works, most of us are less than intentional about how we learn. And, consequently, we take actions that are unconscious, random, or undirected, at worst, or ineffective, at best. Therefore, the next section will attempt to provide that important understanding.

How Learning Works

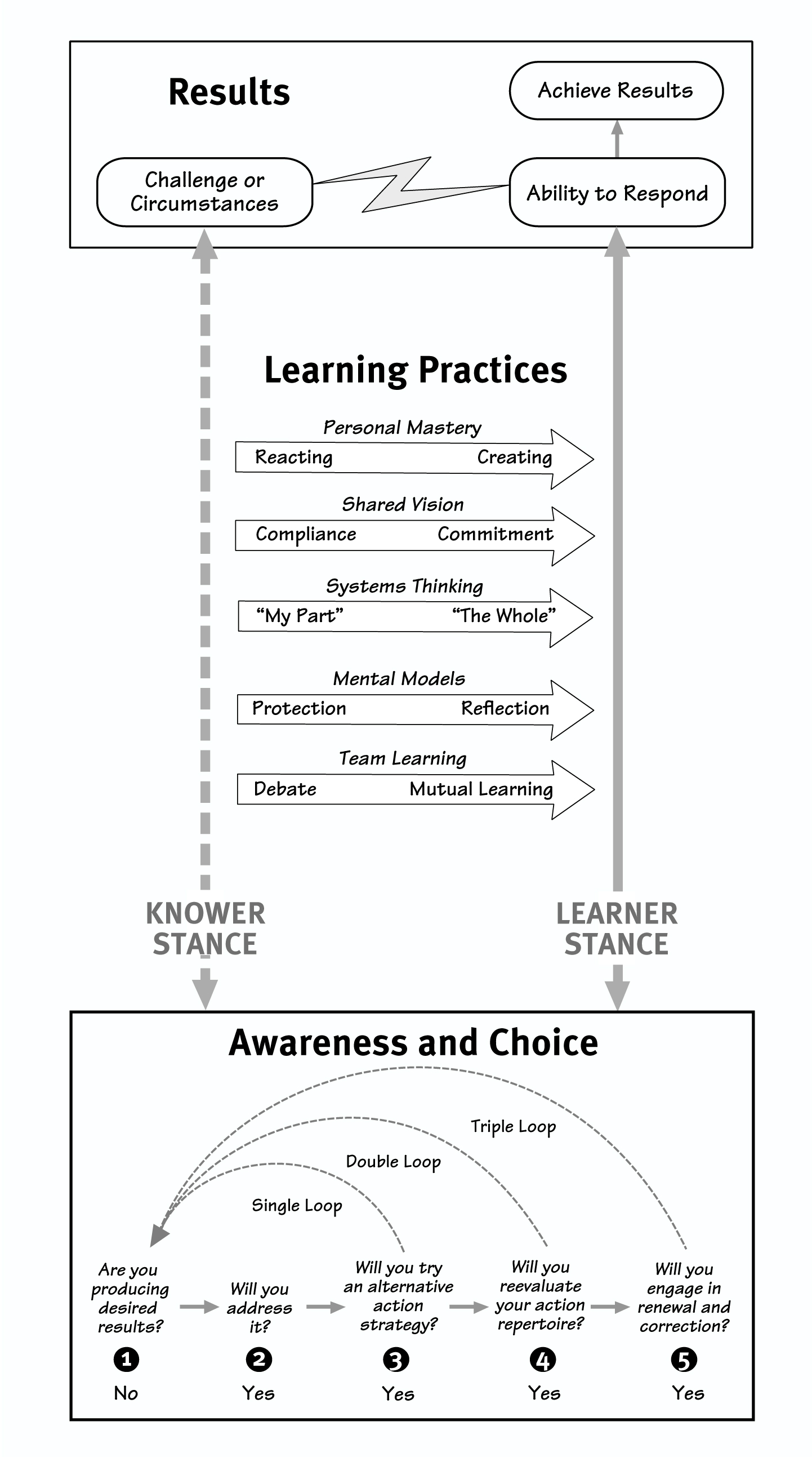

In the most concise, generic form I can express, learning works in the following way (see “A New View of Learning”).

First, you become aware of a discrepancy between “the way things are” and “the way things ought to be”—you realize that you are not achieving desired results.

A NEW VIEW OF LEARNING

Second, you make a choice to address the discrepancy and decide that something has to change. Your response emerges either out of a knower stance, which says someone or something else will have to change (a focus on the circumstances) or a learner stance, which says you will have to change (a focus on your ability to respond to the circumstances).

If you decide to respond out of a knower stance, you will (eventually) become ineffective. New and different challenges and circumstances confront you daily. Responding to tomorrow’s dynamic challenges with your current, static abilities will, over time, lose its effectiveness.

Third, you choose to respond out of the learner stance and decide that you will have to change. So, you will take actions to increase your ability to respond to the circumstances you are facing. If your ability to respond becomes greater than the circumstances, you will achieve positive results, but if the circumstances remain greater than your ability to respond, then you will get negative results.

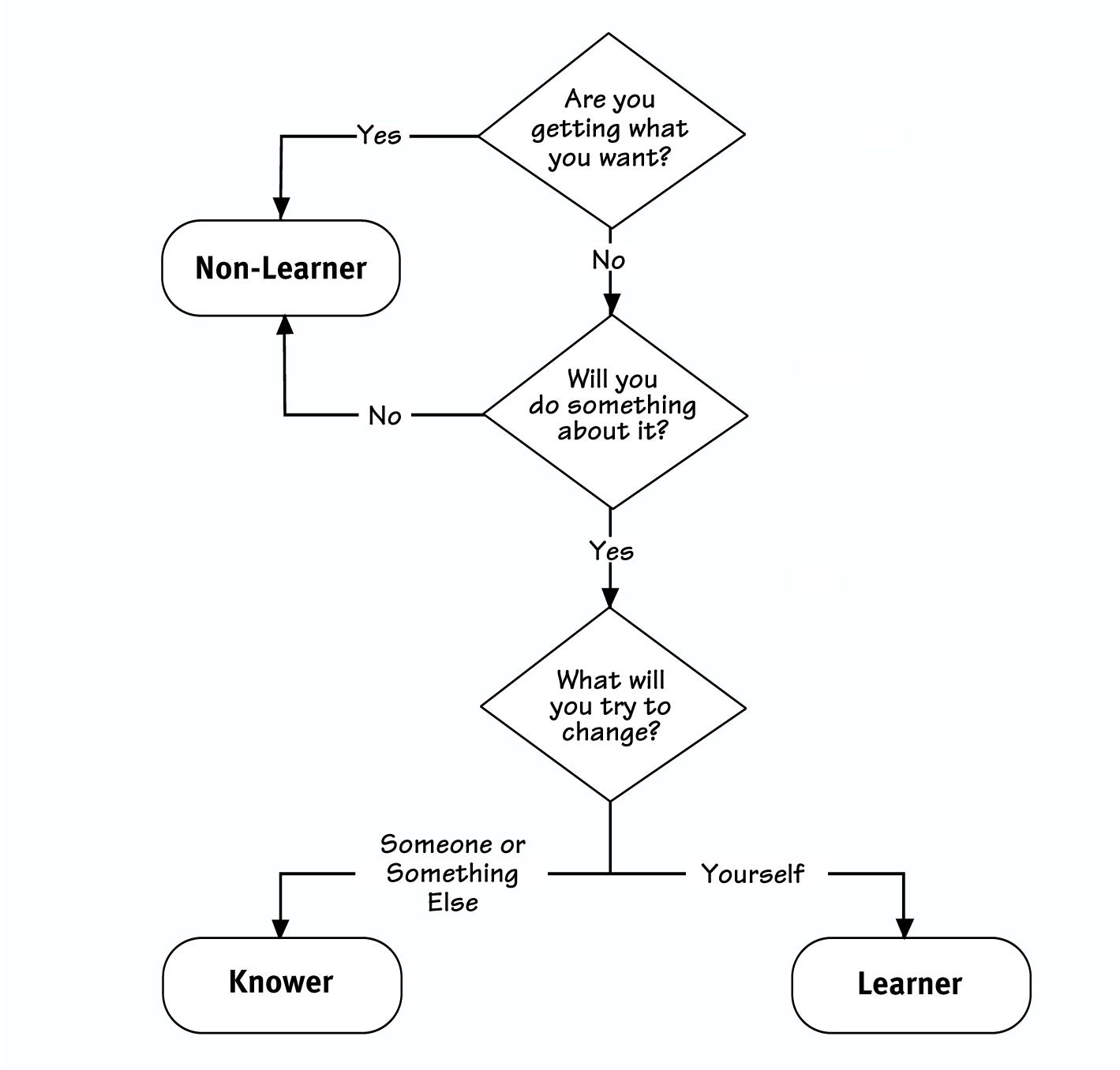

STANCE DECISION TREE

Whether you adopt the knower stance or the learner stance depends on how you answer three questions.

Because learning can be difficult, we all, unfortunately, have a tendency to respond from the knower stance. Making a change requires a direct confrontation with the status quo. And in confronting the status quo, you will eventually discover that your ability to respond is less than you’d like it to be, and this discovery, in turn, may generate feelings of threat or embarrassment. So, in order to protect yourself, you take the stance that someone or something else (i.e., the circumstances) must change. Over time, you become so skilled at this way of reacting that you assimilate these thinking habits into your everyday practice, and they become your knower stance.

Fourth, you will vigilantly notice whenever you are responding out of a knower stance and choose to shift back into the learner stance. You will make this shift easier by diligently employing five learning practices: personal mastery, shared vision, mental models, systems thinking, and team learning. A disciplined application of these five learning practices will help you continually look at yourself as the necessary focus of change and increase your ability to respond appropriately and achieve your desired results.

Awareness and Choice

Many times, the choices we make are hidden from our conscious awareness. For example, when I first got married, I was in the habit of pointing out the flaws in my wife’s suggestions when she proposed an idea with which I disagreed. I figured I was just helping her to “think things through a little more clearly,” when in reality all I was doing was frustrating her to no end. It wasn’t until she pointed out that all I ever did was poke holes in her ideas, without making an alternative suggestion of my own, that I became aware of how my behavior was unfair to her. When I became consciously aware of how I was acting, I could choose to continue with it (perhaps more skillfully, so as not to get caught quite so often), or I could choose to change my behavior, so that it was more productive and caring.

We go through life, to a great extent, unaware of the choices we are making. To be more effective in the world, it is important to consciously operate from a learner stance. So we need a way to wake up our awareness about which stance we are living out of, so we can then make choices — behave in ways — that are in alignment with the learner stance rather than the knower stance. Learning cannot begin without awareness and cannot continue without the making of fundamental choices.

Knower Stance Versus Learner Stance

The terms “knower” and “learner” will be used throughout this article. In short, let’s define a knower as someone who can’t admit that they don’t know something, for fear that doing so will make them look bad. They often pretend that they know things even when they don’t, and they are not willing to be influenced. They are like those know-it-all kids we knew in grade school, except that, as adults, they are much better at hiding it when they don’t know something. Alternatively, let’s define a learner as someone who admits they could be wrong, or that they are uncertain, or that they probably have to change their usual actions in order to achieve their desired results. Learners are willing to be influenced.

Whether you adopt the knower stance or the learner stance depends on how you answer the three questions depicted in the Stance Decision Tree. If you believe you are actually “getting what you want,” you will take on a non-learner stance — there is no need for learning, things are fine, nothing needs to change. If, however, you believe you are not getting what you want, but you don’t want to do something about that discrepancy, then you will, likewise, take on the non-learner stance.

If you believe that you are not getting what you want and you decide that you will do something about it, your next choice is “What will you try to change?” If you attempt to change someone or something else (focus on the circumstances), you are living out of the knower stance, and if you attempt to change yourself (focus on improving your ability to respond), you are living out of the learner stance.

For example, let’s say you become aware that your accounting practices are peppered with errors rather than being the pristine example of proper accounting you thought they were. You are now faced with a choice. How will you address what is happening? If you focus attention on someone or something else, such as why no one ever told you this before, or how you had received poor training in accounting, or how this was fine at the place you used to work, then you are taking a knower stance. On the other hand, if you focus attention on yourself, such as feeling stuck in a rut, or not staying up-to-date on the latest techniques, or lacking passion for doing accounting in the first place, then you are choosing a learner stance. You can tell whether people have taken a learner stance or a knower stance based on where they primarily focus their attention (this is illustrated by the two vertical lines in “A New View of Learning”). If they persistently focus their attention on changing someone or something else, they are living from the knower stance; if they persistently focus on changing themselves, then they have taken a learner stance.

Results

In baseball, home plate is the most important place on the diamond. A run is scored when a player rounds the bases and touches home plate, and not before. It is the central focus of the action—the ball must always be thrown to it or hit from it.

Likewise, achievement of results is the home plate of learning. All learning must be directed to achievement of results or emerge from it. There is no learning without achieving desired results. As illustrated at the top of “A New View of Learning,” results occur through the interaction of (1) the challenge or circumstances we face and (2) our ability to successfully respond to the challenge. When our ability to respond is greater than the challenge itself, then results will be positive; and when the challenge is greater than our ability to respond, we will get negative results.

Let’s bring the baseball analogy a little further. Think of the pitcher as the circumstances or challenges you must face, and think of yourself, and your ability to respond, as the batter. The pitcher hurls challenge after challenge at you. If your ability to respond is greater than the circumstances, you will hit the ball, but if the circumstances are greater than your ability to respond, you will miss the ball or watch it fly past.

The most effective people are always increasing their ability to respond to the changes and challenges they face, and thereby keeping the ratio of “challenge” to “ability to respond” tilted in their favor. On the other hand, when faced with challenging circumstances, less effective people focus their attention on the circumstances rather than increasing their ability to respond. So they blame the circumstances, avoid the circumstances, cover up the circumstances, deny that the circumstances are as bad as they seem, or blame someone or something else for the circumstances.

As an effective baseball player, you would continually seek to increase your ability to hit the ball, no matter who the pitcher is or what type of pitch he is throwing. If you began to frequently strike out, you would focus on your inability to respond and ask, “What part of my hitting needs to improve in order to hit what is being pitched to me?” As an ineffective player, frequently striking out, you would start to question the circumstances (e.g., the umpire isn’t fair; the sun is in my eyes; at least I haven’t struck out as many times as Carlos; I’ve got the wrong bat; etc.) rather than your ability to respond (hitting ability).

You cannot achieve your desired results by focusing attention exclusively on the circumstances rather than on your ability to respond to those circumstances. It doesn’t make sense to ignore the circumstances, however, for they are part of the equation of effectiveness. In fact, you must explore and interact with them. But then you must redirect your energy toward developing the ability to respond successfully to those circumstances.

Learning begins and ends with achievement of desired results. You cannot know whether you have actually learned anything unless and until you compare the results you are getting with those that you desire to achieve.

Five Core Learning Practices

As you become more skillful at catching yourself reacting from the knower stance and, simultaneously, desiring to live more out of the learner stance, you will recognize a need to develop your learning muscles, or your capacity for learning. In order to do so, you will need to practice five fundamental learning disciplines (as Peter Senge described in The Fifth Discipline) — personal mastery, shared vision, mental models, systems thinking, and team learning. As you develop your learning muscles in each of the five disciplines, you will progress along five continuums from a “knower” to a “learner” (illustrated by horizontal arrows in “A New View of Learning”).

As you practice the disciplines, there is a developmental process — a progression away from knower behaviors toward learner behaviors. While there is some risk of labeling people by using such words as “knower” and “learner,” these terms are used in this context as convenient handles to suggest a contrast between “where we are” in our learning journey and “where we want to end up.” You might think of them like those “before” and “after” photographs often used in weight-loss advertisements. You don’t have much of an appreciation for the “after” picture unless it’s contrasted with the “before” picture. Likewise, you don’t much appreciate what it takes to become a learner unless it’s contrasted with living like a knower. This framework is meant to imply that you cannot stay the same and remain effective in your life.

There are many, many learning practices that you can use, including meditation, reading, intuition, reflection, suspending assumptions, dialogue, intention, team-building, productive conversations, and so on. The five learning disciplines that are explored here are not the exclusive practices that you need to master to get to learning “heaven.” Instead, consider them the core disciplines (along with any associated tools, techniques, or practices) that will help you develop your capacity for deeper and richer learning. Many of the learning practices would serve to enhance and build capacity for progressing along one or more of the learning discipline continuums.

Personal Mastery — If you have transitioned from knower to learner along the personal mastery continuum, you will have felt an internal shift from external pressure to internal desire. Formerly, you reacted to external pressures and expectations defined for you by someone or something else, but now you experience an intense internal desire to create the results you truly want in your life. You have developed the ability to bring something new into existence.

Shared Vision — As an advanced practitioner of shared vision, you have shifted from controlling group interactions with a goal of getting compliance from the members to facilitating mutual commitment. You have developed the ability to co-create collective aspiration.

Mental Models — As someone operating from the learner end of the mental models continuum, you have given up defending yourself during conversations using “protection mode” and now embrace self-exploration using “reflection mode.” You have a well-developed ability to distinguish between “myself” and “my view.”

Systems Thinking — An experienced practitioner of systems thinking, you have shifted your perspective from focusing exclusively on “my part” to focusing on “the whole.” You have a well-developed ability to see your role in the whole.

Team Learning — As you have moved from knower to learner along the team learning continuum, you have shifted from directing and debating during group conversations to having group conversations focused on mutual learning. You have a well-developed ability to generate collective insight.

Living As a Learner

The ultimate aim of this article is to help you live your life as a learner, both individually and collectively. Living an effective life — whether it is achieving your ultimate aim or swatting at little problems that annoy you — begins and ends with understanding how learning works. With this understanding, you are in a position to make critical choices. Do you want to take actions based on a knower stance or based on a learner stance? If you see yourself avoiding, covering up, or denying the circumstances or blaming someone or something else for the circumstances, you know you are living from the knower stance. If you see yourself taking actions designed to change someone or something else, without first focusing on changing yourself, you will, again, recognize that you are mired in the knower stance. If you see yourself creating, reflecting, building commitment, seeing your role in the whole, and engaging in mutual learning, you will be aware that you are living from the learner stance.

Becoming aware, making choices, focusing on your ability to respond, and achieving your desired results — this is living your life as a learner.

Brian Hinken is the author of the newly released book, The Learner’s Path: Practices for Recovering Knowers (Pegasus Communications, 2007), from which this article was adapted. He serves as the Organizational Development Facilitator at Gerber Memorial Health Services, a progressive rural hospital in Fremont, MI. Brian is responsible for leadership development, process facilitation, and making organizational learning practically useful for people at all levels of the organization.

NEXT STEPS: TEAM LEARNING

When we seek “emerging knowledge,” ideas that have not yet fully emerged, it is literally impossible to debate the “right” emerging knowledge. It all just emerges. When new ideas are being revealed, there is no debate. We just say to ourselves, “Oh, there’s a new one. And, look, here comes another idea.” When the group reverts back to debating, it is because new thoughts and reflections have ceased to emerge, and we are left with our old biases, assumptions, and perspectives. We know that a team has a high aptitude for team learning when debate is being replaced with suspension of judgment, and when meaningful discussion flows freely among the members of the group.