The sole purpose of a corporation is to maximize return on investment to shareholders.” That is the raison d’etre for most organizations — and many believe it is pointless to develop any other purpose. Proponents of this belief say that any loyal, dedicated officer of a company should have no aspirations aside from providing good financial results as quickly as possible. While the assumption is prevalent, it contradicts the very foundation of learning organization principles and beliefs. According to Peter Senge, it is “the most insidious idea that has crept into mainstream Western management in the last 30 to 40 years.”

VISION DEPLOYMENT MATRIX ™

SIR, THE COMMITTE HAS DONE ITS WE’VE GOT THE MISSION AND PURPOSE ‘DOWN To TWO WORDS: BOTTOM LINE!

Obviously, making money is important. A manager who says profit is unimportant is like a coach who says, “I don’t care if we win or lose.” Both lose credibility in their ability to bring out the best in their teams. But to confuse an essential requirement for success with an organization’s actual purpose is like thinking that breathing is the primary reason for living. Our entire industrial enterprise has been crippled by this erroneous assumption. Yet it is so deeply ingrained that in many circles, anyone who questions it may immediately be called crazy themselves.

“Shifting the Burden” to Return on Investment

Regardless of the origin of the mental model that profitability equals core purpose, managers still feel hamstrung by it. Many feel they can’t focus on core purpose as long as they are bound by this frantic need for short-term profits. But it is a Catch-22: to ultimately meet medium- and long-term bottom-line demands, they must focus on core purpose.

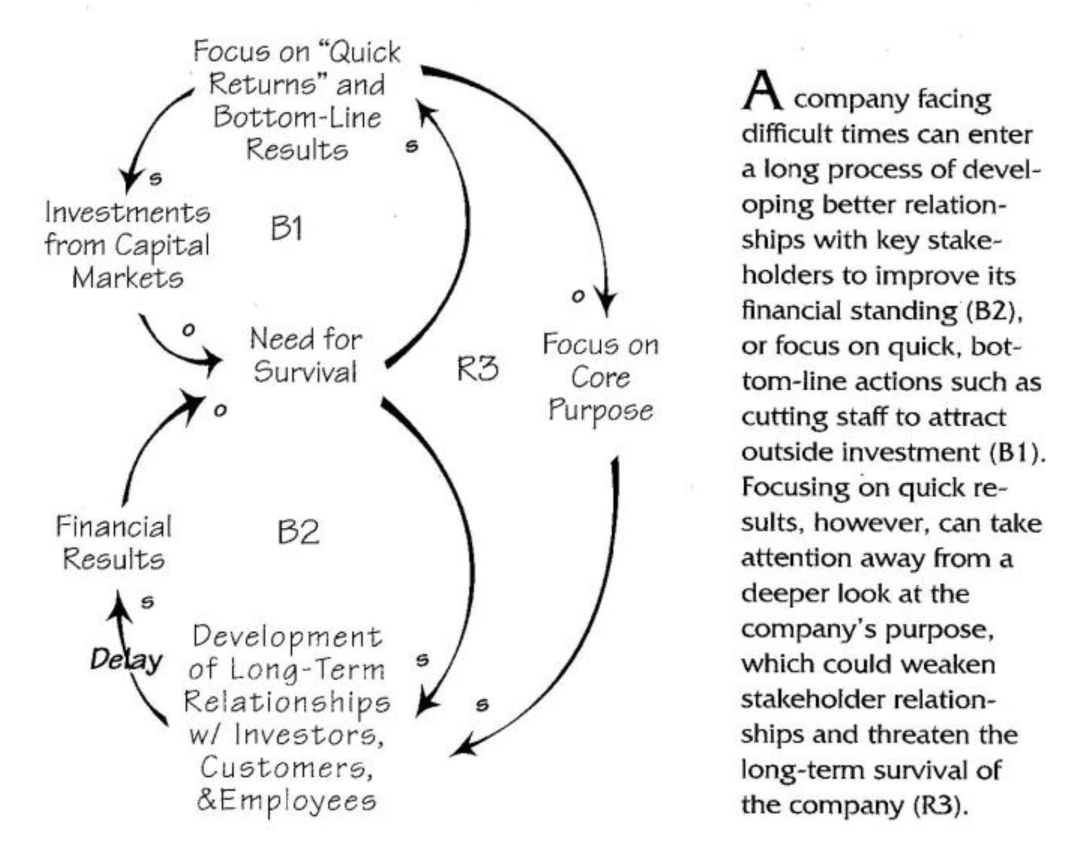

These managers and their organizations are caught in a “Shifting the Burden” dynamic, where a more immediately appealing “quick fix” impairs a system’s ability to address the real root causes of a problem (see “Dangers of Bottom-Line Thinking”). The fundamental solution to this bottom-line focus is a potentially lengthy, soul-searching effort to develop a sense of core purpose and build strong relationships with investors, customers, and employees (B2). Since this kind of process is slow and seemingly risky, many managers opt for the quicker fix: “We’ll show investors we can enhance returns by doing something really dramatic right now.” Declaring “the purpose of our company is maximizing return on investment to stockholders,” they institute tough financial measures, hastily cutting staff and R&D. Improved financial statements attract investment from capital markets, which allows them to survive in the short-term (B1).

But this strategy has dangerous side-effects. While this stance attracts short-term capital, it also demands even more short-term bottom-line measures. The managers’ fear of becoming controlled by the numbers becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. And to long-term investors, this approach telegraphs a lack of focus on the business itself.

Customers. Meanwhile, the company has also sent an implicit message to customers: “The fundamental purpose of our firm is returning investment to shareholders. We merely depend upon you for our revenues.” Which can be interpreted as: “We’re willing to make money off you in any way we can.” This may be one of the key causes of eroding brand loyalty, because customers realize (possibly through a decline in product quality or through more aggressive marketing) that the customer relationship is no longer fundamental. The eroding loyalty in turn reinforces the belief among managers that customers only care about price. Over time, the company can drift into becoming a low value-added commodity producer.

Employees. In addition, the implicit message of a “return on investment” focus for employees is the same: “Our purpose is to use you as a resource and make a buck off your back in whatever way we can.” This intangible factor often evokes bitter, expensive labor-management battles and sharp declines in morale. Any company that focuses all its energies toward maximizing profits has a remarkably different feel than one where personal and shared visions are as important as monthly financial statements.

Top Management. A similar pressure bears on the top management team. The new short-term focus adds powerful reinforcement to the idea that managers should put aside their personal wants, aspirations, feelings, and desires to add value, and focus on the corporation’s financial measures. The senior managers’ potential vision, creative force, and effort thus remains untapped. The managers become like sports players who spend every possible moment looking over their shoulders at the score board instead of focusing on the game.

The Alternative: Building Purpose from Scratch

In “Shifting the Burden” structures, the greatest leverage always comes from finding your way back to the fundamental solution. This may mean weaning your company from the “maximum return” addiction and raising capital by aligning investors, employees, and customers with your purpose and vision.

At Hanover Insurance, for example, former president Bill O’Brien spent 20 years defining his company’s vision, values, and sense of common purpose. “In those days,” he explains, “when mainstream businessmen believed the only purpose of business was making money, we were very radical. We said that the purpose of our company was three-fold: to give the American people the maximum value for their property and liability insurance dollar, to provide each employee with the help and environment necessary to become all he or she was capable of becoming, and to earn a profit to fuel our growth, provide for a rainy day, and reward ourselves. It was a mission statement, although nobody had heard of that word yet.”

Part of O’Brien’s work at Hanover involved developing a set of core values by which the company and all of the employees would operate. These included:

- merit—making decisions based on intended results, not on politics

- openness—being more honest in communications among employees and with shareholders

- localness—making decisions at the level closest to the problem

These principles helped operationalize the vision in a way that all stake-holders could see and understand. For example, the value of openness led to a rethinking of how shareholder reports were written. According to O’Brien, “I had worked in four companies before Hanover, and had seen first-hand how sometimes the reports to shareholders were not forthright interpretations of actual performance…. Not only did the shareholders tend to see through this, but it also made it impossible for employees to trust us…. At Hanover, starting in the 1970s, we sent the same report to front-line managers as we sent the board of directors, with no spin on the news.”

The alternative to the hard work of clarifying vision and values that occurred at Hanover is to arm yourself against potential invaders and maintain a high stock price at all costs. But this cultivates a negative vision, and negative visions tend to backfire. Building a corporation whose stock price reflects the value we create, on the other hand, can be a positive, motivating experience for all employees.

Core Purpose and Performance

We have seen some powerful linkages between this work on defining core purpose and the deeper examination of a company’s core competencies and economic value. Gary Hamel and C.K. Pahalad’s work, for example, in Competing for the Future, describes the definition of a company’s core competencies as key to developing an enduring competitive advantage for the future. It is not enough, they argue, to design new products and develop patents; a company must view the competencies that reside in those processes as their competitive advantage. However, identifying what areas to develop competence in requires a clear sense of organizational purpose.

Another approach that is complementary to clarifying core purpose and core competencies is EVA (Economic Value Added), an analytical framework that challenges many traditional notions of corporate financial performance, including narrow definitions of profitability and earnings per share. EVA is described in the book The Quest for Value, by G. Bennett Stewart III (Harper Collins, 1991), and is being used with substantial success by companies such as Coca-Cola and Quaker Oats.

Developing an enduring vision for an organization is not an immediate process, and it will certainly take longer than simply decreeing that all employees must produce more return to share-holders. Every organization’s process for developing its sense of purpose will be different — depending in large part upon the current relationship between the company and its investors, employees, and customers. Building such a purpose means embarking on a developmental journey, but unless organizations begin the journey, they will, in effect, be adrift — with no purpose at all.

For more on developing a corporate strategy for building a shared vision, see “Building Shared Vision: How to Begin.- The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook (New York: Doubleday. 1994). page 312. Hanover Insurance’s experience Is described In more detail on page 306 of the Fieldbook.

Art Kleiner is co-author and editorial director of The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook, and author of the forthcoming The Age of Heretics, a history of the social movement to change large corporations for the better.

Bryan Smith is co-author of The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook and president of Innovation Associates of Canada (Toronto, Ontario).

A company facing difficult times can enter a long process of developing better relationships with key stake-holders to improve its financial standing (B2), or focus on quick, bottom-line actions such as cutting staff to attract outside Investment (B1). Focusing on quick results. However, can take attention away from a deeper look at the company’s purpose. Which could weaken stakeholder relationships and threaten the long-term survival of the company (R3).