Anyone working to build a learning organization will, sooner or later, run up against the challenge of “proving” the value of what he or she has done. Without some form of assessment, it is difficult to learn from experience, transfer learning, or help an organization replicate results.

But assessment strikes fear in most people’s hearts. The word itself draws forth a strong, gut-level memory of being evaluated and measured, whether through grades in school, ranking in competitions, or promotions on the job. As writer Sue Miller Hurst has pointed out, most people have an intrinsic ability to judge their progress. But schools and workplaces subjugate that natural assessment to the judgment of teachers, supervisors, and other “experts,” whose appraisals determine promotions, wealth, status, and, ultimately, self-esteem.

Assessing Learning

Is it possible to use assessment in the service of learning? Can assessment be used to provide guidance and support for improving performance, rather than elicit fear, resentment, and resignation? This has been a guiding question at the MIT Center for Organizational Learning for several years, as we have struggled to find a reasonable way to assess learning efforts. The motivations are essentially pragmatic: our corporate affiliates need some idea of the return on their investments, and we as researchers need a better understanding of our work.

To create a new system of assessment, we started by going back to the source — to the people who initiate and implement systems work, learning laboratories, or other pilot projects in large organizations. We then tried to capture and convey the experiences and understandings of these groups of people. The result is a much-needed document that moves beyond strict assessment into the realm of institutional memory. We call it a “learning history.”

The Roots of a New Storytelling

A learning history is a written document or series of documents that is disseminated to help an organization become better aware of its own learning efforts. The history includes not just reports of action and results, but also the underlying assumptions and reactions of a variety of people (including people who did not support the learning effort). No one individual view, not even that of senior managers, can encompass more than a fraction of what actually goes on in a complex project — and this reality is reflected in the learning history. All participants reading the history should feel that their own points of view were treated fairly and that they understand many other people’s perspectives.

A learning history draws upon theory and techniques from ethnography, journalism, action research, oral history, and theater. Ethnography provides the science and art of cultural investigation — primarily the systematic approach of participant observation, interviewing, and archival research. From journalism come the skills of getting to the heart of a story and presenting it in a way that draws people in. Action research brings to the learning history effective methods for developing the capacities of learners to reflect upon and assess the results of their efforts. Finally, the tradition of oral historians offers a data collection method for providing rich, natural descriptions of complex events, using the voice of a narrator who took part in the events. All of these techniques help the readers of a learning history understand how participants attributed meaning to their experience.

Each part of the learning history process — interviews, analysis, editing, circulating drafts, and follow-up — is intended to broaden and deepen learning throughout the organization by providing a forum for reflecting on the process and substantiating the results. This process can be beneficial not only for the original participants, but also for researchers and consultants who advised them — and ultimately for anyone in the organization who is interested in the organization’s learning process.

Insiders versus Outsiders

One goal of the learning history work is to develop managers’ abilities to reflect upon, articulate, and understand complex issues. The process helps people to hone their assessments more sharply by communicating them to others. And because a learning history forces people to include and analyze highly complex, dynamic interdependencies in their stories, people understand those interdependencies more clearly.

In addition, the approach of a learning history is different from that of traditional ethnographic research. While ethnographers define themselves as “outsiders” observing how those inside the cultural system make sense of their world, a learning history includes both an insider’s understanding and an outsider’s perspective.

Having an outside, “objective” observer is an essential element of the learning history. In any successful learning effort, people undergo a transformation. As they develop capabilities together, gain insights, and shift their shared mental models, they change their assumptions about work and interrelationships. This collective shift reorients them so that they see history differently. They can then find it difficult to communicate their learning to others who still hold the old frame of reference. An outside observer can help bridge this gap by adding comments in the history such as, “This situation is typical of many pilot projects,” or by asking questions such as, “How could the pilot team, given their enthusiasm, have prevented the rest of the organization from seeing them as some sort of cult?”

Similarly, retaining the subjective stance of the internal managers is important for making the learning history relevant to the organization. In most assessments, experts offer their judgment and the company managers receive it without gaining any ability to reflect and assess their own efforts. The stance of a learning history, on the other hand, borrows from the concept of the “jointly told tale,” a device used by a number of ethnographers in which the story is “told” not by the external anthropologist or the “naive” native being studied, but by both together. For these reasons, the most successful learning history projects to date seem to involve teams of insiders (managers assigned to produce and facilitate the learning history) working closely with “outside” writers and researchers hired on a contractual basis.

Results versus Experience and Skills

Companies today don’t have a lot of slack resources or extra cash. Thus, in every learning effort, managers feel pressured to justify the expense and time of the effort by proving it led to concrete results. But a viable learning effort may not produce tangible results for several years, and the most important results may include new ways of thinking and behaving that appear dysfunctional at first to the rest of the organization. (More than one leader of a successful learning effort has been reprimanded for being “out of control.”) In today’s company environment of downsizing and re-engineering, this pressure for results undermines the essence of what a learning organization effort tries to achieve.

One goal of the learning history work is to develop managers’ abilities to reflect upon, articulate, and understand complex issues.

Yet incorporating results into the history is vital. How else can we think competently about the value of a learning effort? We might trace examples where a company took dramatically different actions because of its learning organization efforts, but it is difficult to construct rigorous data to show that an isolated example is typical. Alternatively, we might merely assess skills and experience. A learning historian might be satisfied, for instance, with saying, “The team now communicates much more effectively, and people can understand complex systems.” But that will be unpersuasive — indeed, almost meaningless — to outsiders.

In this context, assessment means listening to what people have to say, asking critical questions, and engaging people in their own inquiries: “How do we know we achieved something of value here? How much of that new innovation can we honestly link to the learning effort?” Different people often bring different perceptions of a “notable result” and its causes, and bringing those perceptions together leads to a common understanding with intrinsic validity.

For example, one corporation’s learning history described a new manufacturing prototype that was developed by the team. On the surface, this achievement was a matter of pure engineering, but it would not have been possible without the learning effort. Some team members had learned new skills to communicate effectively with outside contractors (who were key architects of the prototype), while others had gained the confidence to propose the prototype’s budget. Still others had learned to engage with each other across functional boundaries to make the prototype work. Until the stories of these half-dozen people were brought together, they were not aware of the common causes of each other’s contributions, and others in the company were unaware of the entire process. The learning history thus included a measurable “result” — the new prototype saved millions of dollars in rework costs — but simply reporting a recipe for constructing new prototypes would be of limited value. At best, it would help other teams mimic the original team, but it wouldn’t help them learn to create their own innovations. Only stories, which deal with intangibles such as creating an atmosphere of open inquiry, can convey the necessary knowledge to get the next team started on its own learning cycle.

The Strength of the Story

Some learning histories have been created after a project is over. Participants are interviewed retrospectively, and the results of the pilot project are more-or-less known and accepted. Other histories are researched while the story unfolds, and the learning historian sits in on key meetings and interviews people about events that may have taken place the day before. “Mini-histories” may be produced from these interviews, so that the team members can reflect on their own efforts as they go along and improve the learning effort while it is still underway. But such reflection carries a burden of added discipline: it adds to the pressure on the learning historian to “prove results” on the spot, to serve a political agenda, or to justify having a learning history in the first place.

HOW TO CREATE A LEARNING HISTORY

While every learning history project is different, we have found the following steps and components useful. See page 5 for an excerpt from an actual learning history.

Accumulate Data

Start by gathering information through interviews, notes, meeting transcripts, artifacts, and reports. For a project that involved about 250 people, we found we needed to interview at least 40 individuals from all levels and perspectives to get a full sense of the project. We try to interview key people several times, because they often understand things more clearly the second or third time. It is useful to come up with an interview protocol based on notable results (e.g., “Which results from this project do you think are significant, and what else can you tell us about them?”). All interviews in our work are audiotaped and transcribed.

Sort the Material

Once you have gathered “a mess of stuff” accumulated on a computer disk, you will want to sort it. Try to group the material into themes, using some social science coding and statistical techniques, if necessary, to judge the prevalence of a given theme. This analysis produces a “sorted and tabulated mess of stuff” that will become an ongoing resource for the learning history group as it proceeds. The learning historians might work for several years with this material, continually expanding and reconsidering it. They can use it as an ongoing resource, spinning off several documents, presentations, and reports from the same material.

Write the Learning History

At some point, whether the presentation is in print or another medium, it must be written. Generally, we produce components in the order given here, although they may not necessarily appear in that order in the final document:

- Notable results: How do we know that this is a team worth writing about? Because they broke performance records, cut delivery times in half, returned 8 million dollars to the budget, or made people feel more fulfilled? Include whatever indicators are significant in your organization. It is helpful to use notable results as a jumping-off point, particularly if you are willing to investigate the underlying assumptions—the reasons why your organization finds these particular results notable. Often, a tangible result (the number of engineering changes introduced on a production line) signifies an intangible gain (the willingness of engineers to address problems early, because they feel less fear).

- A curtain-raiser: What will the audience see when the drama opens? We begin by thinking very carefully about how the learning history opens. The curtain-raiser must engage people and give them a flavor for the full story without overwhelming them with plot details. The curtain-raiser may be a vignette or a thematic point; often, it’s a striking and self-contained facet of the whole.

- Nut ’graf: (journalism jargon for the thematic center of a news story). If you only had one or two paragraphs to tell the entire learning history, what would you put in those paragraphs? Even if this thematic point doesn’t appear in the final draft, it will help focus your attention all the way through the drafting.

- Closing: What tune will the audience be singing when they leave the theater? How do you want them to be thinking and feeling when they close the report or walk away from the presentation? You may not keep the closing in its first draft form, but it is essential to consider the closing early in your process because it shapes the direction that the rest of your narrative will take.

- Plot: How do you get people from the curtain-raiser to the closing? Will it be strictly chronological? Will you break the narrative up into thematic components? Or will you follow specific characters throughout the story? Every learning history demands a different type of plot, and we try to think carefully about the effects of the different styles before choosing one. So far we have found that many plots revolve around key themes, such as “Innovation in the Project” and “Engaging the Larger System.” Each theme then has its own curtain-raiser, nut ’graf, plot, and closing.

- Exposition: What happened where, when, and with whom? Here is where you say there were 512 people on the team, meeting in two separate buildings, who worked together from 1993 to 1995, etc. The exposition must be told, but it often has no thematic value. It should be placed somewhere near the beginning, but after the nut ’graf.

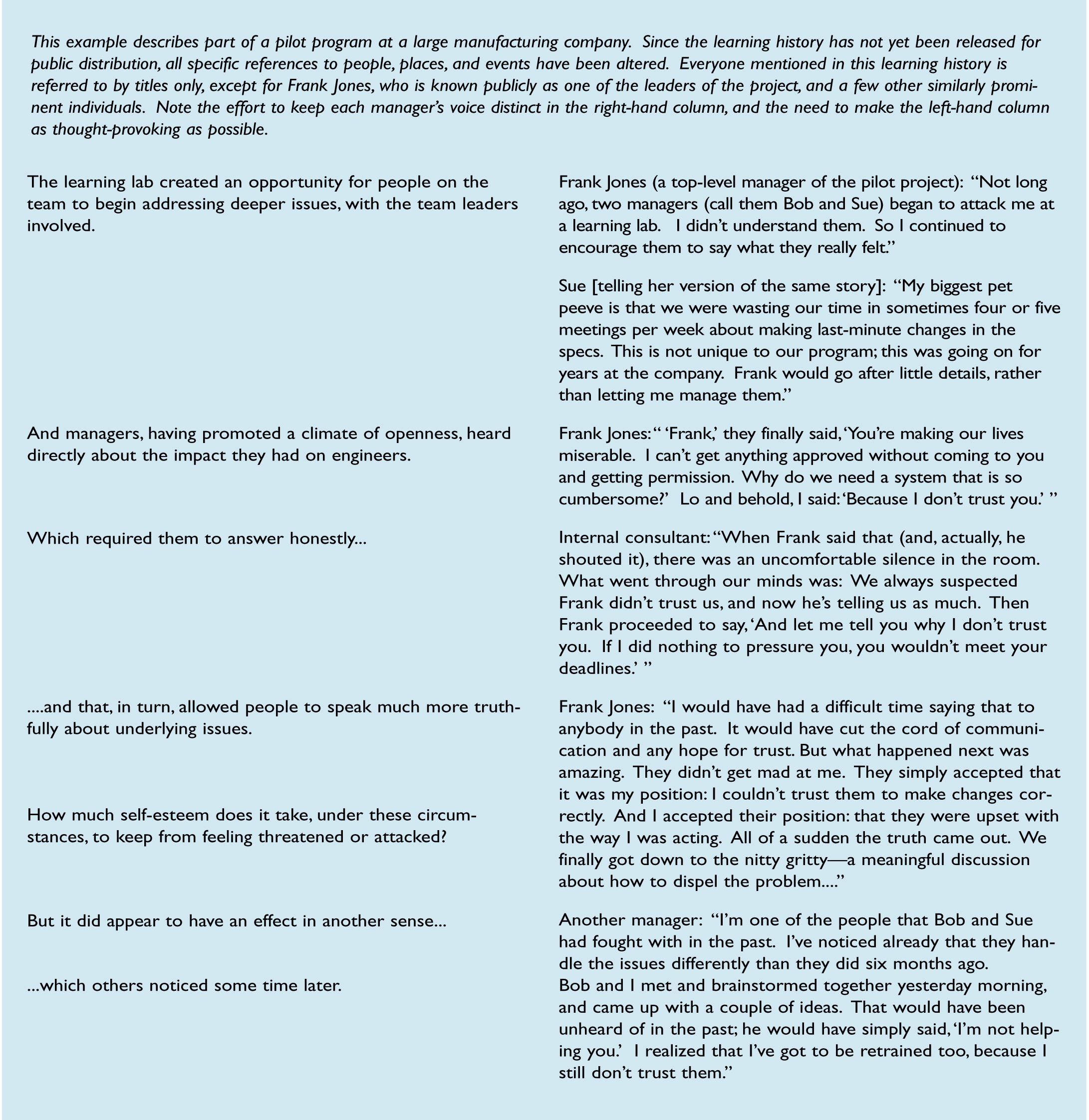

- The right-hand column (jointly told tale): So far, the most effective learning histories tell as much of the story as possible in the words of participants. We like to separate these narratives by placing them in a right hand column on the page. We interview participants and then condense their words into a well-rendered form, as close as possible to the spirit of what they mean to say. Finally, we check the draft of their own words with each speaker before anyone else sees it.

- The left-hand column (questions and comments): In the left column, we have found it effective to insert questions, comments, and explanations that help the reader make sense of the narrative in the right-hand column.

To create an ongoing learning history, an organization must embrace a transformational approach to learning. Instead of simply learning to “do what we have always done a little bit better,” transformational learning involves re-examining everything we do—including how we think and see the world, and our role in it. This often means letting go of our existing knowledge and competencies, recognizing that they may prevent us from learning new things. This is a challenging and painful endeavor, and learning histories bring us face to face with it. When the learning history is being compiled simultaneously with the learning effort, then the challenge and pain of examining existing frameworks is continuous. But to make the best of a “real-time” learning history, admitting and publicizing mistakes must be seen as a sign of strength. Uncertainty can no longer be a sign of indecisiveness, because reflecting on a learning effort inevitably leads people to think about muddled, self-contradictory situations. Much work still needs to be done on setting the organizational context for an ongoing learning history so that it doesn’t set off flames that burn up the organization’s good will and resources.

Currently, there are almost a dozen learning history projects in progress at the Learning Center. In pursuing this work, we no longer talk about “assessing” our work. Instead, we talk about capturing the history of the learning process. It is amazing how this approach and new language changes the tenor of the project. People want to share what they have learned. They want others to know what they have done — not in a self-serving fashion, but so others know what worked and what didn’t work. They don’t want to be assessed. They want their story told.

George Roth is an organizational researcher with the MIT Center for Organizational Learning and a consultant active in the study of organizational culture, change, and new technology introduction.

Art Kleiner is co-author and editorial director of The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook, and author of the forthcoming The Age of Heretics, a history of the social movement to change large corporations for the better.