In the May 1999 issue of The Systems Thinker, we focused on an unfortunate trend that has arisen in the retail industry: failure to file with the courts “reaffirmations,” or special deals that some stores have made with bankrupt credit-card customers in order to collect bad debts. As we saw, companies that neglect to file these arrangements risk FBI investigation and heavy fines (as Sears discovered).

A team from Arthur Andersen Business Consulting in London rose to the Workout challenge and sent in some intriguing causal loop diagrams capturing various aspects of the story—from the culture at Sears, to the role of financial pressure on retail stores, to buying patterns of individual customers. We’ve printed several analyses here.

Levers for Change?

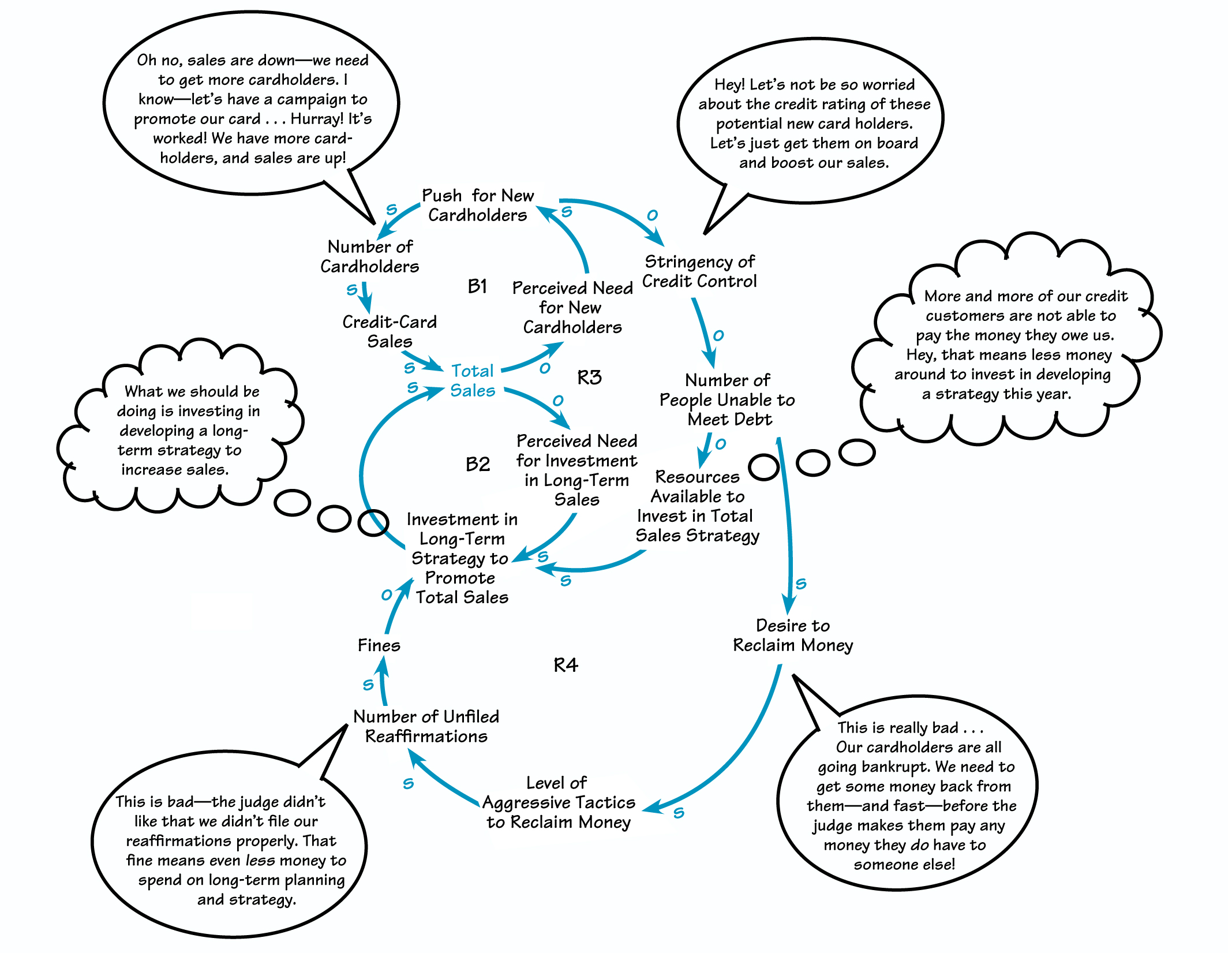

As these analyses make clear, the retail-industry “reaff scandal is complex and can be explored from a number of different perspectives. How might companies begin to untangle these complexities and avoid the trap into which Sears fell? Becky Martin suggests three possible levers for improving matters: (1) watching for the pitfalls of an aggressive, “can do” culture, (2) resisting the temptation to neglect long-term sales strategy investments, and (3) insisting on stringent evaluation of new customers’ credit ratings. For any company that relies substantially on extending credit as a way to boost revenue, Sears’ story offers both some hard lessons and some valuable ideas for managing the intricate systemic structures at work.

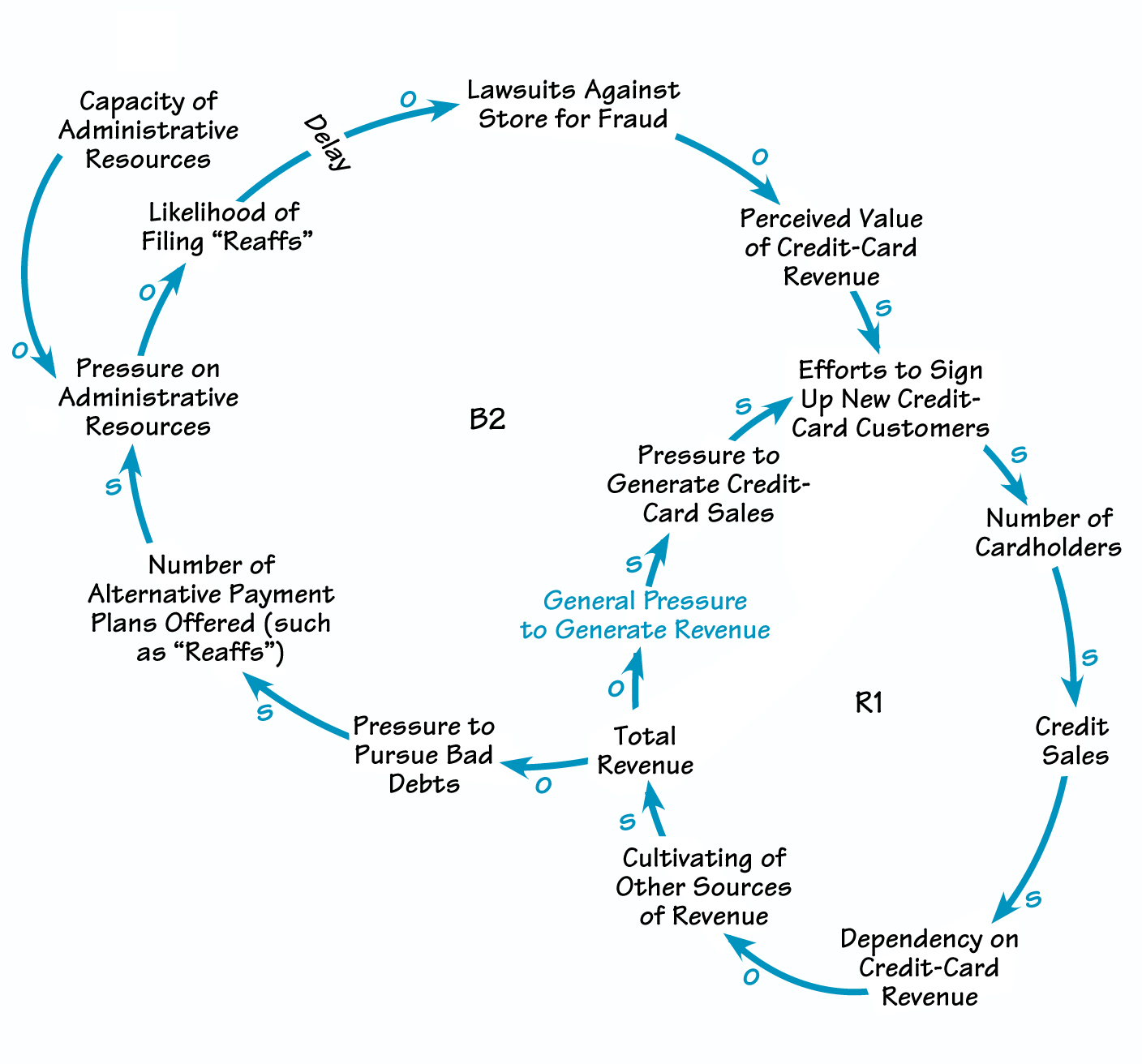

Hooked on Credit-Card Revenue

Our first analysis tells the story of Sears’ reliance on credit-card revenue and the strain that supposed solutions like “reaffs” can put on a system. This analysis features a causal loop structure that is represented here as a composite of two contributors’ work: David Stephens from Arthur Andersen and Michael Crockett from Pegasus Communications.

In this scenario, general pressure to stimulate revenue leads the company to focus on credit-card proceeds as a possible financial boost (R1). But as the number of cardholders and debtors increases, dependency on credit-card revenue also rises. The company invests less in cultivating other sources of income. As a result, total revenue decreases, once again putting pressure on the organization to go after the “low-hanging fruit”: signing up more credit-card customers.

A drop in total revenue has another effect: It puts pressure on the company to pursue bad debts. In Sears’ case, the temptation to offer more payment schemes (, “reaffs”) proved all too strong. The increasing number of reaffs strained the company’s administrative and other resources, reducing the likelihood of correctly filing the reaffs. Eventually, lawsuits were filed against the retail store for credit-card fraud—which has ultimately cooled the company’s enthusiasm for credit-card revenue in general (B2)

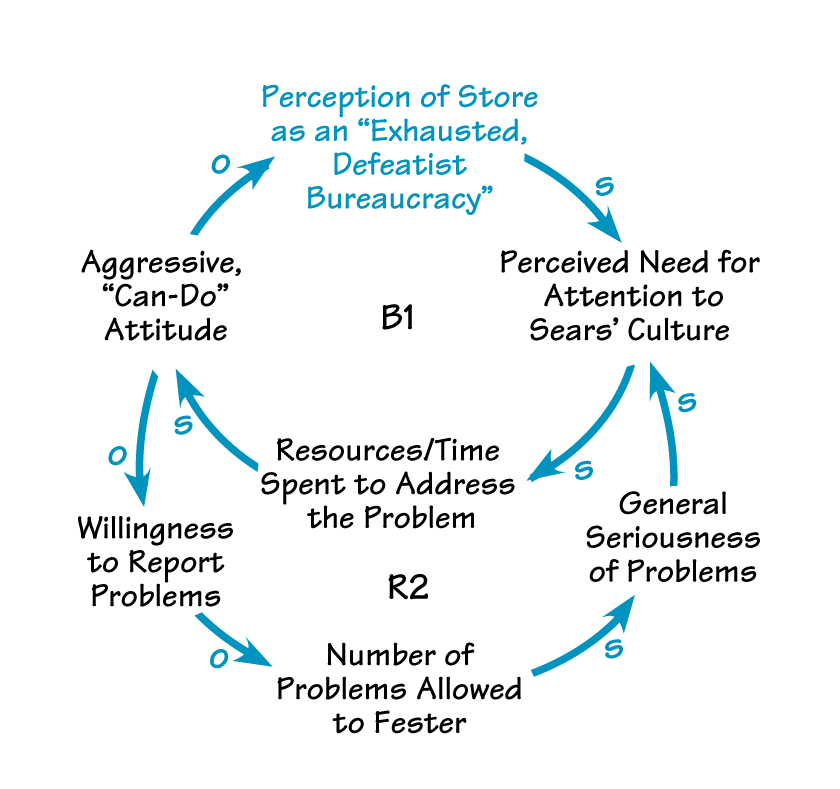

The Folly of Arrogance: A Cultural Fix That Failed

In Andrew Crossley’s analysis, the structure tells the story of a cultural “fix that failed.” The story begins with public judging of Sears (in this case) as an “exhausted, defeatist bureaucracy” (B1). This reputation would prompt many organizations to devote attention and resources to remaking their image, resulting in an “aggressive, can-do” attitude that does in fact achieve the desired effect.

However, a cocky or arrogant attitude by employees can have its downside: less willingness to report problems. When this happens, the number of problems allowed to fester—such as unethical filing practices—rises, which heightens the general seriousness of the company’s problems (R2). Once more, the organization is driven to take action, which strengthens the “can-do” spirit even more. As this reinforcing process accelerates, the organization becomes less and less willing to acknowledge its very real problems.

Draining Long-Term Investment Capacity

Our final analysis, offered by Becky Martin of Arthur Andersen, shows how Sears’ decisions created three major drains on the company’s ability to invest in long-term sales strategies. (The diagram also gives us an intriguing glimpse into the possible mental models driving Sears’ decisions.) As Becky’s diagram shows, a drop in sales prompts the company to sign up more new cardholders (B1). This temporarily increases total sales, but it also reduces the company’s motivation to invest in more long-term sales strategies (B2). The push for new credit customers has another result as well: As the campaign intensifies, the company becomes less stringent in evaluating new customers’ credit ratings (R3). As a result, the number of credit customers who can’t pay their debt increases. Resources available for investment in long-term sales strategies plummet, once more reducing actual investments. And last, as the number of debtors rises, the company’s desire to reclaim its money intensifies (R4). The company resorts to more aggressive tactics (even to the point of illegality), gets slapped with hefty fines, and once more has less money available to invest in longer term sales strategies.