When costs go up, the logical thing to do is to pass them along to someone else, right? For the past several years, that’s the tactic that many health plans have adopted in response to rising prescription drug costs. And according to a 2002 study by Rand Corp. of nearly 421,000 workers in the late 1990s, doubling employee co-pays caused companies’ average yearly drug expenses per worker to decline 22 percent (B1 in “Failing to Fix Healthcare Expenses”).

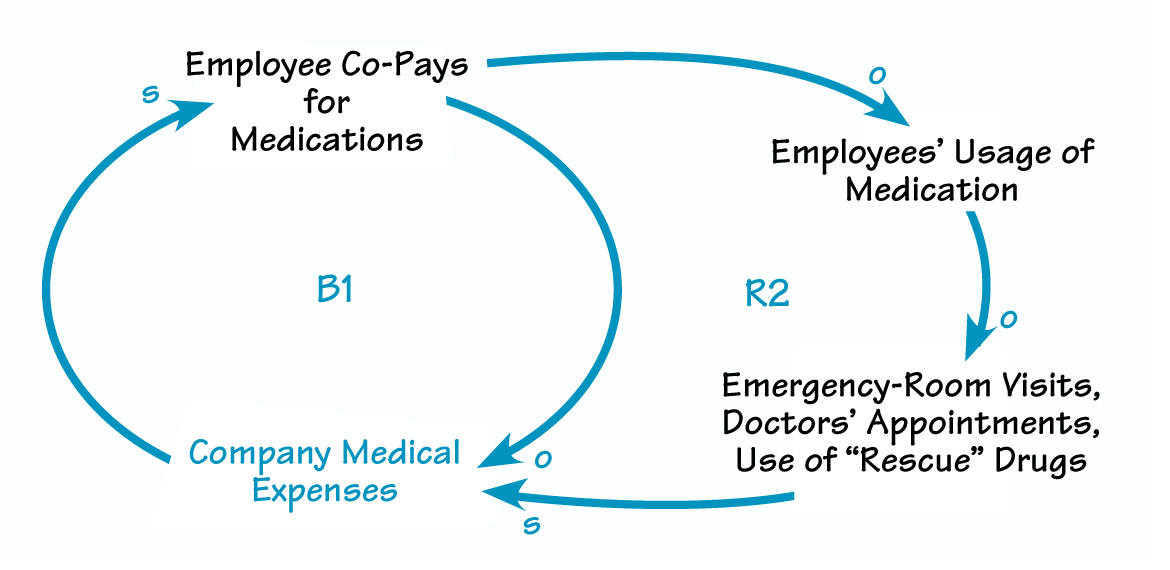

FAILING TO FIX HEALTHCARE EXPENSES

In response to rising healthcare expenses, many companies have increased employee co-pays for medications. Over the short run, that action reduces the companies’ medical costs (B1). But over the long run, employees may fail to refill their prescriptions, leading to more emergency-room visits and use of “rescue” drugs for patients with diabetes and asthma and boosting company medical expenses (R2).

But Pitney Bowes, the world’s leading provider of integrated mail and document management systems, services, and solutions, with 35,000 employees worldwide, wanted to explore ways to reduce healthcare costs even more. The company looked at the variables that caused medical expenses for individual employees to jump dramatically in one year and discovered that patients with asthma or diabetes who failed to refill prescriptions were most at risk.

These findings jibed with a report in the December 2003 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine that up to a fifth of people stopped taking necessary medications when co-pays went up. As a result, many of these patients ended up needing more expensive treatment down the road, in the form of emergency-room visits, doctors’ appointments, and so-called “rescue medicines” (R2).

Based on its research, in the fall of 2001, Pitney Bowes reduced employee co-pays for all asthma and diabetes prescriptions to 10 percent. The result: Use of the medications has gone up, overall expenses for employees with those chronic illnesses have fallen, and the company will save at least $1 million in healthcare costs in 2004.

Based on its analysis, Pitney Bowes doesn’t plan to reduce co-pays for other conditions. But this case does show the benefit of considering both the short- and long-term outcomes of policies to be sure that a proposed intervention doesn’t end up having the opposite effect—in this case, both on the quality of care for employees and the financial bottom line for the company—than intended.

Janice Molloy (janicem@pegasuscom.com) is content director at Pegasus Communications and managing editor of The Systems Thinker.