DECEMBER 22,1989 — The takeover of First American Bank & Trust in North Palm Beach, FL marks the third-biggest bank failure of the year. Fast growth was First American’s trademark, and real estate was its engine. Despite warnings of lax management and inadequate loan documentation, the FDIC did not examine the bank from 1982-1986. Periodic exams were left to local regulators, who were reluctant to act on potential problems while First American was still making money. By 1988, nonperforming loans tripled to approximately $120 million, capturing regulators’ attention and resulting in its eventual takeover.

FEBRUARY 26, 1990 — Imperial Savings of San Diego, CA was taken over by regulators today, adding one more name to the state’s list of failed savings and loans. Imperial fell victim to its own diversification plans, which included a $1.3 billion investment in junk bonds and shaky car loans from a now-defunct broker. Deregulation is blamed in part for Imperial’s troubles, because it enabled the thrift to diversify into speculative financial areas.

APRIL 15, 199I — The takeover of First Executive Life Insurance Company today marked the largest collapse in the insurance industry’s history. The company’s phenomenal success in the 1980s was due to its array of deposit-type products with high interest rates, which were covered by investments in junk bonds with even higher expected returns. When the junk bond market crashed, First Executive’s junk bond portfolio — totaling $8 billion at its peak—also soured, bringing the company down with it. By early 1990 First Executive was showing signs of strain, but it took a full year for regulators to act.

First Executive is only the latest casualty in a financial industry crisis that has been unfolding over the last several years. From S&L’s to banks to insurance companies, once-solid institutions have fallen like dominoes. When the savings & loan debacle brought down the FSLIC and prompted a government bailout, many analysts pointed out that banks were quite different from S&L’s. When banks began to fail in record numbers and the solvency of the FDIC was at risk, they argued that the insurance industry was not vulnerable to the same risks as the banks. Now the insurance industry is being shaken to its foundations, and there is little comfort in the late-blooming realization that perhaps they all had something in common.

“The story is all too familiar: speculative investments led to dizzying growth in the boom years of the 1980s, and then sent many financial institutions into a tailspin when the speculative bubble burst.”

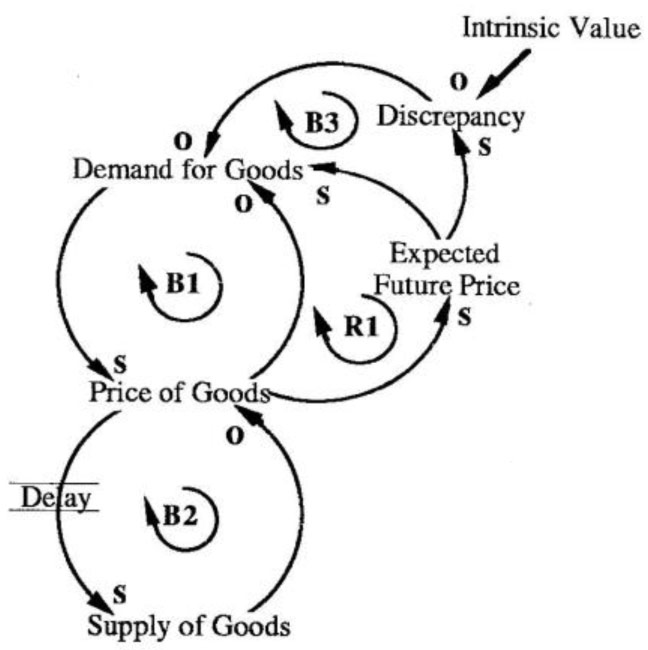

The fall of First Executive is the latest event that has grabbed the headlines, but the story behind it is all too familiar: speculative investments led to dizzying growth in the boom years of the 1980s, and then sent many financial institutions into a tailspin when the speculative bubble burst (see “Speculation Dynamics” diagram). S&L’s and banks, caught up in the upward spiral of the speculation loop, lent money freely to businesses and real estate developments. Insurance companies like First Executive fueled their own growth by relying heavily on junk bonds and risky real estate investments which depended on the speculative bubble continuing to soar.

Many of those investments came crashing down when the junk bond and real estate markets soured. In the case of First Executive, the collapse of the junk bond market signaled the beginning of its problems. Its death spiral was accelerated by knowledgeable policyholders who began pulling out money as word of the company’s problems spread. These withdrawals further dragged down the company’s finances and fueled more pullouts. The average number of redemption requests swelled from 60-70 per day in the first quarter of this year to 260 per day last month.

But how could all this happen? After all, banks and insurance companies are supposed to be exemplars of sound investment, masters of restraint. Bankers are expected to be shrewd – carefully scrutinizing the soundness of every investment before risking the capital of their stakeholders. Insurance companies are icons of conservative investments. So, what went wrong?

Shifting the Burden to Regulators

If you are looking for a scapegoat, say the newspapers, look no further than the government regulators. The hue and cry in the media is “where were the regulators?” A Business Week article (April 22, 1991), for example, said “Insurance watchdogs complain that they are understaffed, underfunded, and hamstrung by weak state laws. But the current crop of failures shows that even where tough laws exist, regulators were often loath to enforce them aggressively.” In case after case, blame is laid on the regulators for not intervening early enough to prevent disaster.

According to Fortune magazine, the moral of the First Executive story is that policyholders “cannot take the safety of their policies for granted.” But in fact, ever since the implementation of the Federal Deposit Insurance Company (FDIC) in the 1930s, Americans have been encouraged to do precisely that. Bank patrons have been continually reassured about the safety of their investments and their deposits. The result is that consumers, for the most part, are unaware and unconcerned about their financial institution’s investment practices. Their primary consideration when choosing a company is who pays the highest yield.

Speculation Dynamics

Financial institutions themselves have become more liberal in their business practices as they have learned to rely on the regulators to play the watchdog role. With customers clamoring for high yields, they pursued the highest return investments without much apparent concern for the risks associated with them. The result is that the role of safeguarding investments has been shifted from the individual to the insurance company, bank, or S&L, and from those institutions to the federal regulators (see “FDIC: Has the Cure Become Worse than the Bite?” Systems Sleuth, September 1990).

Assuming Responsibility Again

Federal insurance funds and regulators were never meant to be a substitute for prudent investment and lending practices. They were designed to bolster confidence in a system that had been badly beaten during the Great Depression years. The last thing we should want to do now is build an even stronger reliance on regulators by expanding their powers or establishing tougher regulations—actions that would only further increase our dependency.

Instead, the regulatory body’s role should be to maximize information flows by providing and enforcing reporting standards with which market players can better evaluate investment risks for themselves. The high yields on speculative investments are usually commensurate with the level of risk involved, and if the true risk-to-return ratios are known, the market itself will self-select the appropriate mix of investments.

Tighter regulations alone won’t prevent a repeat of the First Executive disaster. The real leverage lies in educating all consumers about the true risk of their investments. Each of us, as individuals or as institutions, must then assume the responsibility of making prudent choices about where to put our money.