We all have had the experience of becoming so engaged in an activity that we lose track of everything except for that task; for instance, playing the squash match of our lives, meeting an important, pressing deadline, or enjoying team camaraderie during an intense collaborative effort. When you finally glance at the clock, you are shocked to notice that hours have passed, although it seemed like minutes.

Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls this phenomenon flow. Flow is the experience of being actively involved in a challenging task that stretches our abilities to the extent that time, space, and self-awareness become secondary to the accomplishment of that task. According to Csikszentmihalyi, who has developed and studied the concept of flow over the past 30 years, it is “the process of total involvement with life.” The individual becomes the activity or process and loses his or her sense of identity or separateness. The result is an outcome that usually exceeds expectations and may accomplish things that we never imagined.

Although flow cannot be turned on and off, we can create conditions that facilitate its onset. Prerequisites for being “in flow” include matching the individual to the level of complexity of the task and empowering

OUT OF FLOW

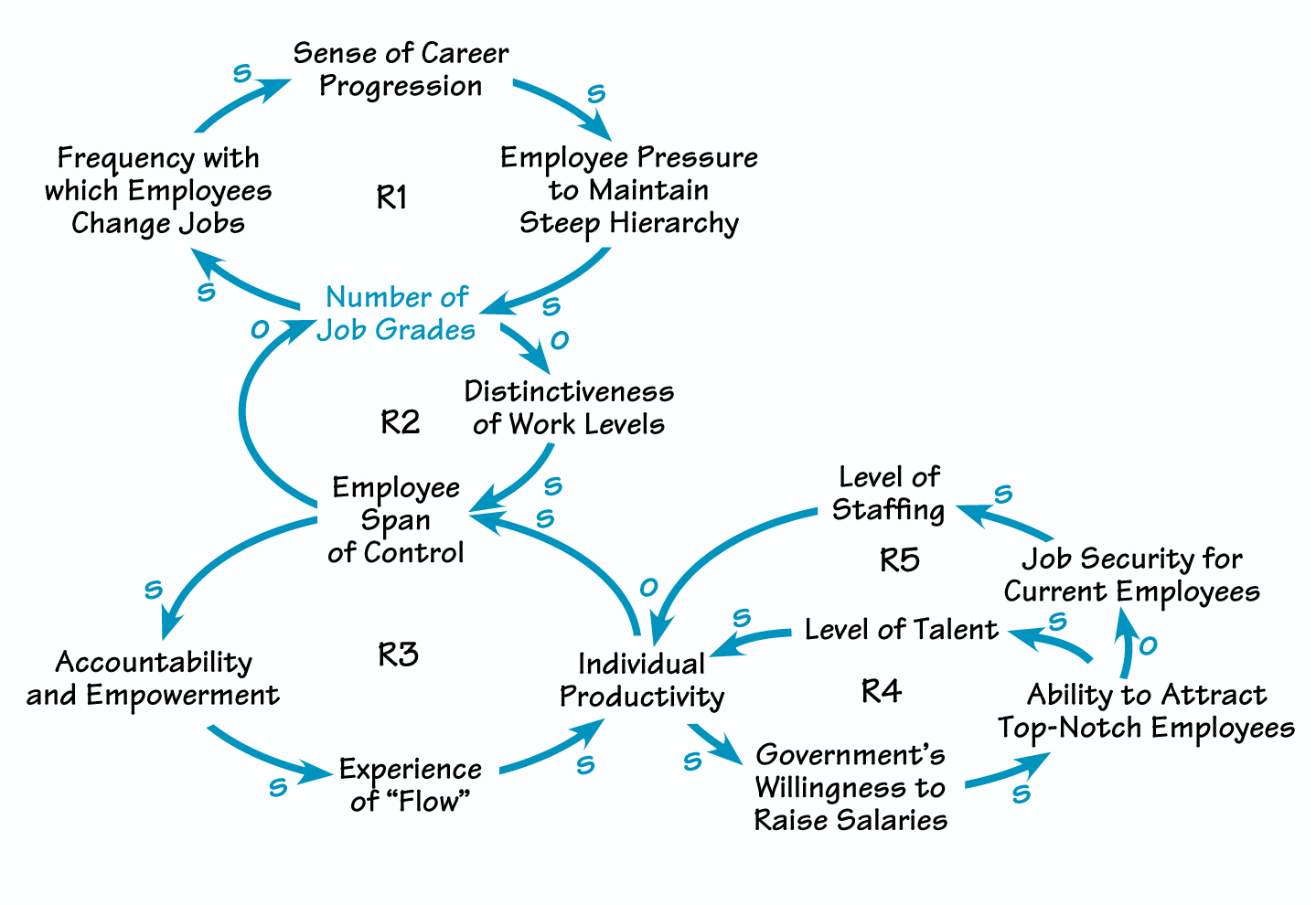

Over time, the number of grade levels within the U. K. Civil Service has risen (R1). Employees welcome this configuration, because it offers them the ability to rise up the career ladder relatively quickly. But with many job grades, no level is sufficiently distinct from the one below and the one above it (R2). This kind of redundancy leads to people being out of flow (R3) and lowers productivity. Lower productivity undermines the quality of talent available to the public sector (R4 and R5) and inflates staffing levels.

him or her to achieve that task. We may be pulled “out of flow” when the project is too difficult or too easy, or when we are not clear about what the responsibility entails or who “owns” it. Any of these scenarios can lead to boredom, frustration, stress— and lower productivity.

Too Many Cooks?

In working with government agencies in the United Kingdom, we found that employees are often out of flow when their organization has more than five or six levels of hierarchy. In a very real sense, “too many cooks spoil the broth”; public-sector organizations in the U. K. may not perform as well as private-sector companies do because too many people are assigned to work that does not contribute to the organization’s mission. Looking at this issue from a systemic perspective shows that cutting the number of levels in these government organizations—and, in turn, the number of employees—could actually drive up productivity by enhancing employees’ sense of flow.

This dynamic is shown in more detail in “Out of Flow,” a diagram developed in workshops with senior U. K. civil servants. Loop R1 depicts the situation that has evolved over decades, in which each organization includes 11 job grades, or steps in the career ladder. For example, the job grades in one organization went from administrative assistant to administrative officer to executive officer to higher executive officer to senior executive officer and so on.

Employees welcome this configuration, because it offers them the ability to rise up the ladder relatively quickly. Indeed, people often stay in a post for only two or three years, even at fairly strategic levels. This structure benefits the individuals, but not necessarily the implementation of a strategy that may take five years to come to fruition!

Loops R2 and R3 reveal the more insidious consequences of this fairly steep, step-driven hierarchy. With many job grades, no level is sufficiently distinct from the one below and the one above it. This is particularly true if each job grade also represents a step in the hierarchy of accountabilities.

A hierarchy with numerous layers of accountability reduces everyone’s degree of accountability. If middle managers report to middle managers who then report to middle managers, who is accountable for translating strategy into action? What is the added value between one manager and another? In one government department we looked at, we found three job grades in the work level that should translate the strategy into means of delivery and three job grades in what people would recognize as middle management.

This kind of redundancy leads to people being out of flow, because they are often more capable than the assignments they are given and because they aren’t empowered to make things happen. In addition, when several people assume responsibility for a functional area with no clear-cut distinction in their roles, real accountability becomes blurred to the extent that no one is actually in charge. Where there is no accountability for outputs, productivity inevitably drops.

To compound the problem, the U. K. Government does not significantly increase the pay of public-sector workers unless they achieve productivity gains. Given this background and other cultural factors, the Civil Service pays less than private-sector companies for equivalent levels of work. This discrepancy reduces the quality of the talent available to the public sector (R4).

Finally, loop R5 serves to ensure that this system stays in place. Policymakers value job security for civil servants, which makes it difficult to reduce the number of employees other than by attrition. Without the ability to reduce staffing levels, departments struggle to make productivity gains. And without productivity gains, managers cannot offer employees competitive pay raises.

Getting Back in Flow

Our research indicates that optimal work levels are ones where employees pass down added value to those at the next level and empower them to accomplish their goals. For example, top management sets the strategy for middle managers to put into action. Middle managers work with the operational staff to ensure that they have the resources to meet performance, time, and cost targets. Supervisors, technicians, and front-line operations staff then accomplish the necessary tasks. This organizational structure allows workers to be truly empowered to deliver distinctive outputs for the level of work that they are in and that are needed for the organization to fulfill its mission, thus increasing flow.

From this perspective, we believe that attempts to improve productivity in the U. K. Civil Service must involve determining the appropriate number of work levels for each organization, with probably a maximum of five or six from top to bottom of any distinct unit. As suggested by the dynamics shown in “Out of Flow,” streamlining the work levels will let organizations reduce staffing, pay higher salaries, and compete with the private sector for the best talent.

Paradoxically, fewer organizational levels may lead to a greater sense of real career steps. A promotion really would be a promotion to a new and distinct work level. Also, senior-level people might spend longer in a post, providing a more coherent long-term strategy. The experience of the U. K. Civil Service indicates that more people will be in flow as a result of this process. They will perform better on the job and enjoy their work experience more than when they were operating within a heavily layered hierarchy. Although this framework developed out of the experience of U. K. Government departments, it is likely to apply to any organization with too many levels for value-added activities to cascade efficiently from the top to the bottom (see “A Recipe for Success”).

Given the very low levels of unemployment in the U. K., this is an excellent time to consider streamlining government bureaucracy. This issue is fraught with obvious political and social consequences that must be understood and minimized. However, consider the deleterious effect of thousands of civil servants effectively working out of flow, through no fault of their own. If flow is the recipe for releasing the potential of all staff in bureaucratic organizations, then we need to look for the right number of cooks to make a new broth.

Robert Bolton (Robert. Bolton@KPMG. CO. UK) is the director of Workforce Solutions at KPMG Consulting in London, England.

A RECIPE FOR SUCCESS

- What proportion of staff/cost is devoted to value-added activities?

- What is the average span of control? Experts often use the ratio of one manager to six staff people as a benchmark average. But if the staff is truly empowered, then managers should be able to have 10 or 15 direct reports or even more.

- How many work levels are there? Are middle managers reporting to middle managers, and therefore not adding value to each other?

- What proportion of staff is involved in front-line activities, i.e., the organization’s central mission?

- Are there areas of the organization that could benefit from a process structure based on horizontal endto-end business processes but that currently use a vertically driven functional structure or vice versa?