The field of organizational learning has long offered a rich selection of tools — from devices such as the Ladder of Inference to causal loop diagrams to computer simulation models and more. As George Rothand Art Kleiner make clear with the publication of their new book Car Launch: The Human Side of Managing Change(Oxford University Press,2000), learning histories are a worthy addition to any manager’s “toolbox.”

Car Launchis the first volume in Oxford University Press’s new series of learning histories. The book describes a change effort undertaken by a project team at a major U. S. auto manufacturer (given the pseudonym of AutoCo) in the early 1990s. The industry involved, and the particulars of the story, are dramatic in themselves. Indeed, the book will likely hold many readers’ interest from cover to cover. However, it’s the larger lessons about change that constitute the true value of this and any other learning history.

What Is a Learning History?

ANATOMY OF A LEARNING HISTORY

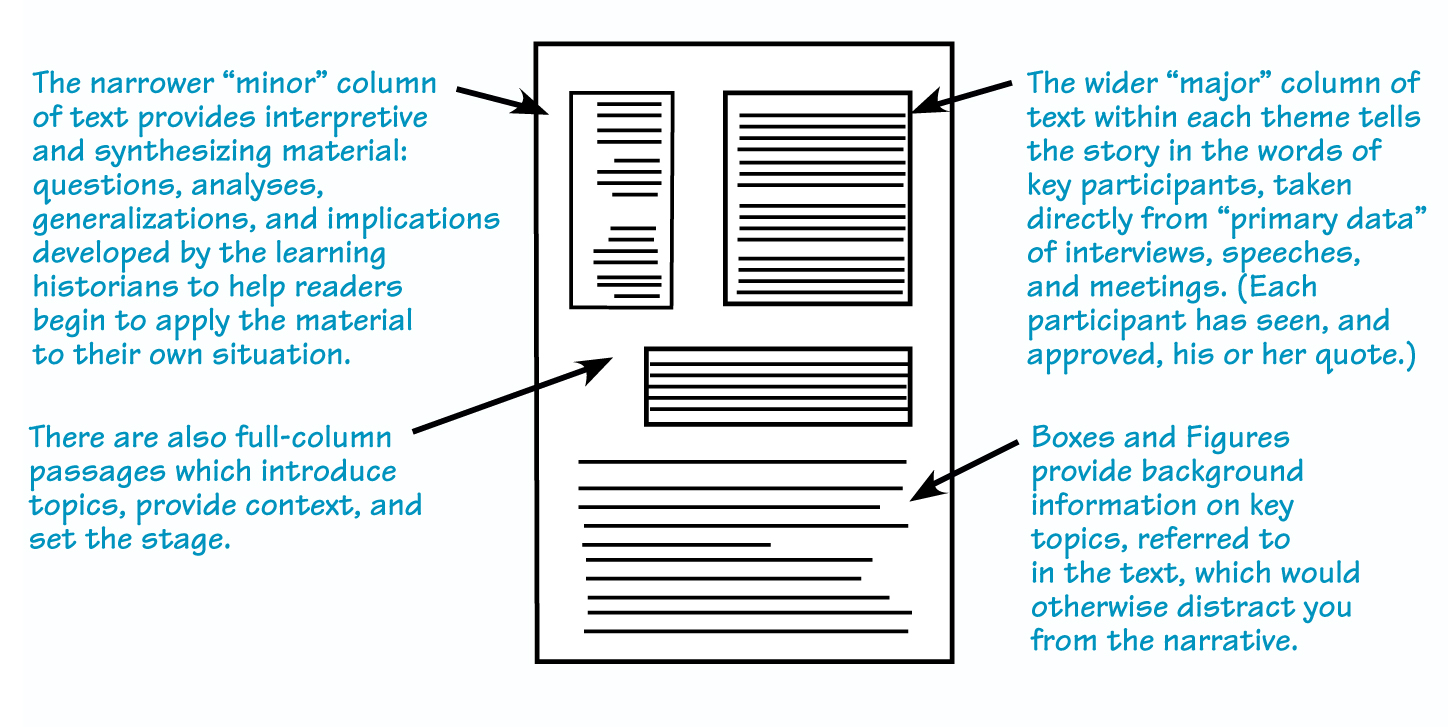

The format used in Car Launch organizes information into interpretive material, contextual explanations, direct quotations from participants, and background material on key topics.

What exactly is a learning history? It’s a document that records an organization’s learning journey from the skills developed to the results achieved and lessons gained. Car Launch was created through a series of interviews with AutoCo employees and the consultants who worked with them throughout the course of their learning initiative. The document has a specific, “anatomy” that structures the information into categories (see “Anatomy of a Learning History”). Each page spread features a mix of lengthy quotations from key players, and interpretations and questions for thought from the authors (the learning historians). Full-column passages provide context and set the stage for understanding the quotations, and boxes offer background information on important topics or tools referred to in the story. Readers may digest the information in any sequence they choose.

Roughly the second half of the book contains special chapters to enrich readers’ understanding of the AutoCo story and to guide facilitators in the practical use of learning histories as a tool. Specifically, Peter Senge provides an analysis of the story from an organizational learning perspective; Rosabeth Moss Kantor addresses AutoCo’s experience from the perspective of organizational change; and George Roth has contributed a piece examining the AutoCo story through the “lens” of action science. The volume finishes with a reader’s guide to using Car Launch in organizations and classrooms.

Why Use a Learning History?

Though Car Launch can certainly benefit individual readers, as Roth and Kleiner explain, it is primarily meant to be “a tool for collective learning and for ongoing study and practice….The objective . . . is to produce better conversations in an organization so that it can move forward effectively.”

Of course, a learning history is of primary value to the very organization featured in the document. But it also can be a powerful tool for any organization struggling with similar issues and wishing to learn from others’ experience. A well written learning history can serve as a spring board to dialogue and then effective action, regardless of whether readers actually participated in the actual story. With Car Launch, for example, users don’t necessarily have to be facile with automobile engines or wiring systems to glean important lessons from AutoCo’s experience. The structure of the book is designed to highlight universal challenges that readers from any industry or organization can relate to and benefit from such as the desire to improve communication, the need for stronger community, and a leader’s struggle to build trust within a troubled team.

Getting the Most out of a Learning History

As with any organizational learning tool, introducing a learning history in an organization must be undertaken with care and forethought. Facilitator scan expect to meet with some resistance, apathy, or confusion common responses to perceived new “gadgets” or “programs” being “rolled out” by managers. Roth and Kleiner have some recommendations that facilitators can follow for laying the groundwork:

- Assess the level of interest in and demand for the document. For example, ask, “How much perception is there that the learning history ‘story’ is aligned with the organization’s most important business objectives?”

- “Ask top managers to write cover letters indicating support for the learning process, use of the learning history by interested teams, and the desire for open consideration of the issues . . .raised in the document.”

- “Distribute the learning history as part of voluntary workshops or meetings. Invite people to read it and then, a week or two later, meet . . . to talk through the [document]” and its implications.

- Provide a cover memo to readers explaining the intent of the learning history, and include suggestions for how to read and interpret the document.Once the idea of using the learning history to generate discussion gains acceptance, facilitators can guide the gathering as follows:

- As a group begins to discuss the learning history, look for ways to help team members accumulate a shared understanding of the story. Ask questions such as, “What happened in the story? Why?” “What surprised you in reading this document?” “Where did you find yourself quickly making judgments?” “What information is not in the document that you expected to be there?” “How is what happened in the story similar or dissimilar to your own experiences?”

- Next help the group to begin “link[ing] the past with the present and future.” Ask questions such as, “What generalizations and implications can we draw from the story?”, “What important questions should we think about in order to move forward from here?” “What might be causing the behavior patterns that we wish to change in our own organization?”

An Act of Courage

It takes courage for any group of people to embark on a major learning journey — especially, as happened in Car Launch, when the larger organization is grumbling that the effort is unproven or a waste of time. It takes further courage to agree to have one’s story “warts and all” published and made available to anyone who wants an intimate glimpse into one’s organization and personal views. Although the participants in the AutoCo initiative remain anonymous to the general reading public, they are surely known to one another and to their current colleagues and superiors. Hence they occasionally may still have to defend their involvement in what some at AutoCo see as a controversial approach. For this reason, we owe the participants in Car Launch indeed, in any learning history a debt of gratitude. They are sharing both their triumphs and tragedies so that we may use the lessons they learned to better our own organizations.

NEW AND NOTEWORTHY

Dialogue and the Art of Thinking Together

by William Isaacs (Doubleday/Currency, 1999)

Judging by the interest in sessions on dialogue at the recent Systems Thinking in Action® Conference, this book should prove to be a popular addition to many organizational learning libraries. Isaacs shows how many systemic problems stem from our inability to engage in meaningful dialogue with each other. He offers rich examples and numerous tools to help us revitalize our institutions, our relationships, and ourselves.

Birth of the Chaordic Age

by Dee Hock (Berrett-Koehler, 1999)

In his long-awaited book, Hock, founder, president, and CEO emeritus of VISA International, weaves together the history of that unique enterprise with his own life story and worldview. Through his compelling tale of a lifetime of exploring new concepts of organization and his “MiniMaxims” thought provoking quotations sprinkled through the text — Hock shows how we must reconcile seemingly opposing concepts such as chaos and order in order to face the challenges of the future.

Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution

by Paul Hawken, Amory Lovins, and L. Hunter Lovins (Little, Brown, 1999)

Taking the concept of sustainability to a new level, three leading business visionaries explain how the world is on the verge of a new industrial revolution one that promises to transform our ideas about the nature of commerce. The book synthesizes principles that all businesses need to practice to remain competitive.