Hi, my name is Brian and I am a recovering knower. But for the grace of God, and the disciplines of organizational learning, I would have died a knower. I started knowing at an early age and was praised and rewarded for knowing more than my peers. Gradually, and unknown to me at the time, I began to define myself in terms of being a knower. There were moments when I realized I couldn’t maintain my lead ahead of others in my knowing, so I would quit that activity and redefine it as not important. If I could not be the best knower, I wasn’t going to play the game.

My knowing continued all the way through graduate school and eventually into my first few jobs. Even as my knowing continued to grow, I felt I had it under control. I was young and had the stamina to know late into the night and still work the next day. I received recognition from my peers for these exploits. Sometimes, I would secretly go out and study a subject, even in the middle of the work day, just so I could control a conversation better, appear as if I knew all along, or protect myself from admitting that I really didn’t know what to do next.

Being a knower started out as a harmless way to get noticed and applauded, but it continued as a habit that complicated my life. The pressure increased to keep providing the right answers. I sometimes took panicked action in an attempt to maintain the appearance of effectiveness. I sensed that something wasn’t right, but I never recognized that being a knower was hurting me. Besides, everyone else was doing it, too.

Being a knower finally caught up with me, though, when I lost a job. Even though I presented my case to the people in authority with an abundance of facts, evidence, and documentation, my defense fell short, and I was let go. I had finally hit bottom (more about that later).

Knowers and Learners

When I use the term “knower,” I’m not referring to a person who is somehow defective and will forever carry around that label or implying that what he or she knows is not important. A knower is simply someone who adopts a “knower stance.” A stance is a mental posture, point of view, or particular thinking habit. It is possible to move back and forth between a knower stance and a learner stance.

The difference between a knower and a learner is that a learner is willing to be influenced.

The difference between a knower and a learner, very simply, is that a learner is willing to admit, “I don’t know” and be influenced. Knowers believe that they know all they need to know to address the situations they are responsible for. But, at an even deeper level, knowing is so central to who they are that they sometimes act as if they do know something, even when they don’t. In his excellent article “Learning, Knowledge and Power” (www.axialent.com), Fred Kofman defines a knower as “someone who obtains his self-esteem from appearing to be right.”

As a consequence of adopting this knower stance, knowers can easily become defensive. If they are responsible for addressing an unsatisfactory situation but don’t actually have the ability to get the desired results, in order to hide their not-knowing, they will blame someone or something else, hide the evidence, ignore the situation, or deny that the situation was unsatisfactory in the first place.

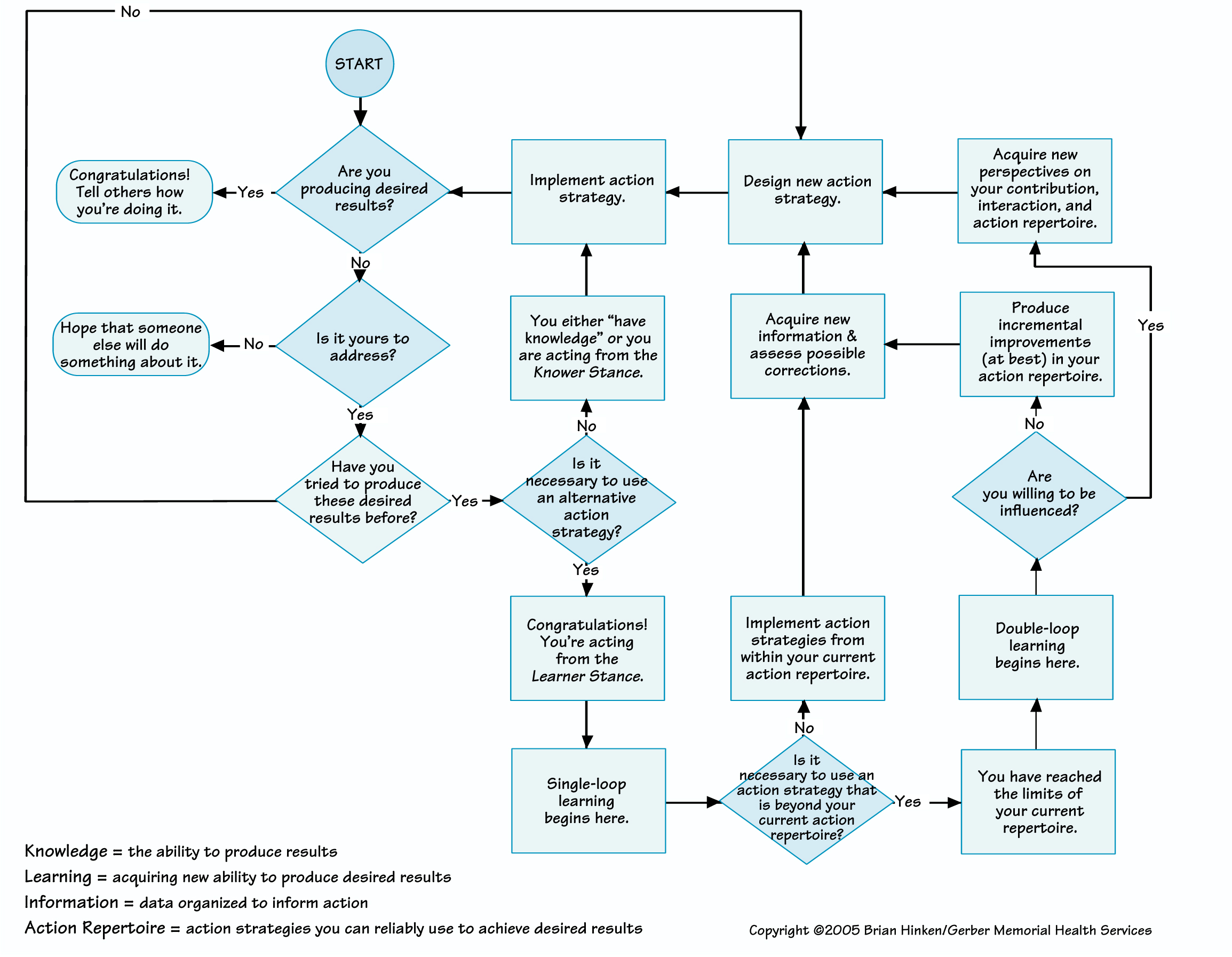

Learners are people who operate from a “learner stance.” They choose a mental posture that includes, at a minimum, three decisions: (1) They admit they are not currently achieving desired results — they want something more or better; (2) They take responsibility for addressing the current unsatisfactory situation; and (3) They admit that what they are presently doing is not producing the desired results. Learners often go deeper and make two more decisions: (4) They admit that, to achieve the desired results, they must go beyond the repertoire of actions they can reliably use; and (5) They are willing to be influenced. These five decisions motivate learners to seek new knowledge (see “Learning Path Decision Tree” on p. 3).

“Having Knowledge” vs. “Being a Knower”

Now, you might be thinking, “What’s wrong with being a knower? Knowers possess valuable knowledge. In fact, employers hire people to a great degree for ‘what they know.’ Therefore, it seems that being a knower actually enhances, rather than hinders, success.” Good point. Knowledge, or the ability to produce desired results through effective actions, is essential for being successful in the world. However, “having knowledge” is not the same thing as “being a knower.”

LEARNING PATH DECISION TREE

When faced with any improvement situation, you can follow the Learning Path Decision Tree to clarify what type of learning will be required in order to achieve your desired results. As you progress through, you are called upon to increase your levels of responsibility, ownership, and self-reflection. This diagram highlights the choices you must make, as well as the accompanying consequences you must accept, as you move further along toward the results that you truly desire.

Both learners and knowers can “have knowledge,” they just use it differently. Knowers effectively apply their knowledge to current situations that are static, definable, and knowable. For example, when a nurse discovers a patient in need of resuscitation, she assesses the situation within seconds and applies her knowledge to that static, definable, knowable situation. She knows what to do in that situation and acts skillfully and confidently. In that circumstance, knowing what to do is a good thing. Most people know exactly what to do in certain defined situations, which is fortunate — especially if you are the patient in that bed.

However, when the current situation changes or if the standard actions are no longer producing desired results, both of which happen frequently in today’s world, knowers become ineffective. In other words, it’s O. K. to be a knower, but not to stay a knower. To paraphrase Eric Hoffer, “In times of change, learners will inherit the earth, while knowers will be perfectly equipped to live in a world that no longer exists.”

In contrast to knowers, learners effectively use their knowledge and expertise not by applying autonomous, unilateral solutions but by inquiring further into the situation. They attempt to implement what they know in order to find out whether or not they actually know it. Learners see their knowledge as only a part of the whole realm of insight surrounding a given situation and not as the single, silver bullet answer.

Secrets of a Knower

As I said earlier, I am a recovering knower. Part of my recovery process is to admit where I have fallen short. These are things that knowers are not particularly proud of, but I share them in the hope that you might recognize some of these tendencies in yourself and seek the help that is prescribed later in this article.

When I am operating from the full-blown knower stance, I adhere to five particular thinking habits; we might refer to these as the “five secrets of a knower”:

- I Live My Life on a Problem-Solving Treadmill. My life is dominated by solving problems. It is how I feel effective and make progress. I derive energy from opportunities to immediately apply what I know against a definable, existing situation. I solve problems to attempt to eliminate the symptoms I am experiencing, rather than to seek any long-term, fundamental solutions. I resist creating lasting solutions to problems because doing so would require me to design something that does not yet exist, thereby admitting that I don’t have the whole picture, and to eliminate the very source of my effectiveness in the world — problems!

- I Force Groups to Comply with My Way. I know that groups work best when all members operate from the same page. Therefore, when I work in groups, I must convince others that I have the “right page” and that all they have to do is follow me. If they suggest alternatives, I try to shut them down or point out problems with their ideas, because we might be headed into untried territory. If I am part of a group where I have authority, I manipulate the members through rewards, punishments, policies, memos, and so on to instill a culture of compliance.

- I Must Protect Myself During Conversations. My objective in every conversation is to win. If I can be seen as right, rational, and not responsible, I have successfully protected my image as a competent person. Any conversation that points out how I may be inaccurate, may be missing something, or may have contributed to a problem must be stopped. I use conversational strategies that counter such threats. I defend my beliefs and conclusions at all costs, because a chink in my self-created armor could cause extraordinary stress for me. It would threaten the core beliefs upon which I base all my knowing.

- I Focus Exclusively on My Own Little Piece of the World. Because my aim is to control things as much as possible and to make things around me predictable, I focus almost exclusively on my team, department, group, family—in short, my realm. If I can make sure that my areas of responsibility perform well, then I can blame areas outside my domain when problems occur.I must also keep the internal workings of my area a secret in order to ensure that I can do things my way. If others suggest how I could do my work better, I react negatively. I resist interacting with outside entities unless I can get something from them that will make my area function more effectively. Even if a suggested change would benefit the organization as a whole, I am resistant to sub-optimizing anything from my realm.

- I Direct and Debate During Group Interactions. I expect group members to interact by playing out predictable, consistent roles, which I reinforce by directing the interaction and controlling the agenda as much as possible. If I can put people in little boxes, then I can better control the process and predict the outcome of our conversations. I constantly bring up what worked for me in the past as a way of maintaining the focus of attention on areas where I have expertise. If I have position power in a group, I use it to manipulate the conversation, so that the outcomes are in line with what I want. And I will often work out the details of a plan in advance and then present the plan for approval. When someone challenges my plan, I make them prove why their approach is better than mine.

Moving Toward the Learner Stance

As I mentioned earlier, about eight years ago, I lost a job, in part because I was a knower and not a learner. I supervised a woman who under-performed, played solitaire, and slept on the job. I tried six different methods to improve her performance, all without success. Both the personnel committee and the full board would not even consider my perspective on this issue. Instead, the board launched a “fact-finding” inquiry, culminating in a final determination meeting. I was pleased to finally be able to tell my side of the story at that meeting, but when I arrived, I discovered that it had already been adjourned. Three board members stayed behind and relieved me of my position.

I had done everything I could think of to improve my situation — including having open and honest conversations, collecting and studying data, experimenting with different tools and techniques, attending workshops, reading books, seeking advice and counsel. But there was one thing I lacked: the willingness to be influenced. I spent a lot of time and effort busily learning all this information, really, just so that I might influence others. I tried to protect myself and focus on my little piece of that world. I didn’t reflect on the bigger picture. I tried to shape groups to conform to my notions, and I moved persistently toward compliance. In short, I displayed classic knower behaviors.

My next job was as organizational development facilitator for Gerber Memorial Health Services. One of my responsibilities was to teach leaders the five disciplines of organizational learning. As a good knower, I set out to learn all that I could about the disciplines, determined to know just a little more than those whom I was teaching. But a funny thing happened —I actually learned this material. And by “learned,” I don’t mean that I merely accumulated more information (which is what knowers think of as learning); I mean I increased my ability to produce desired results. I tried the disciplines out, and, to my amazement, they actually made a difference in my life and work. Below, I will describe how I used them to overcome the five secrets of a knower mentioned earlier (see “Shifting from Knowing to Learning” on p. 4).

Personal Mastery

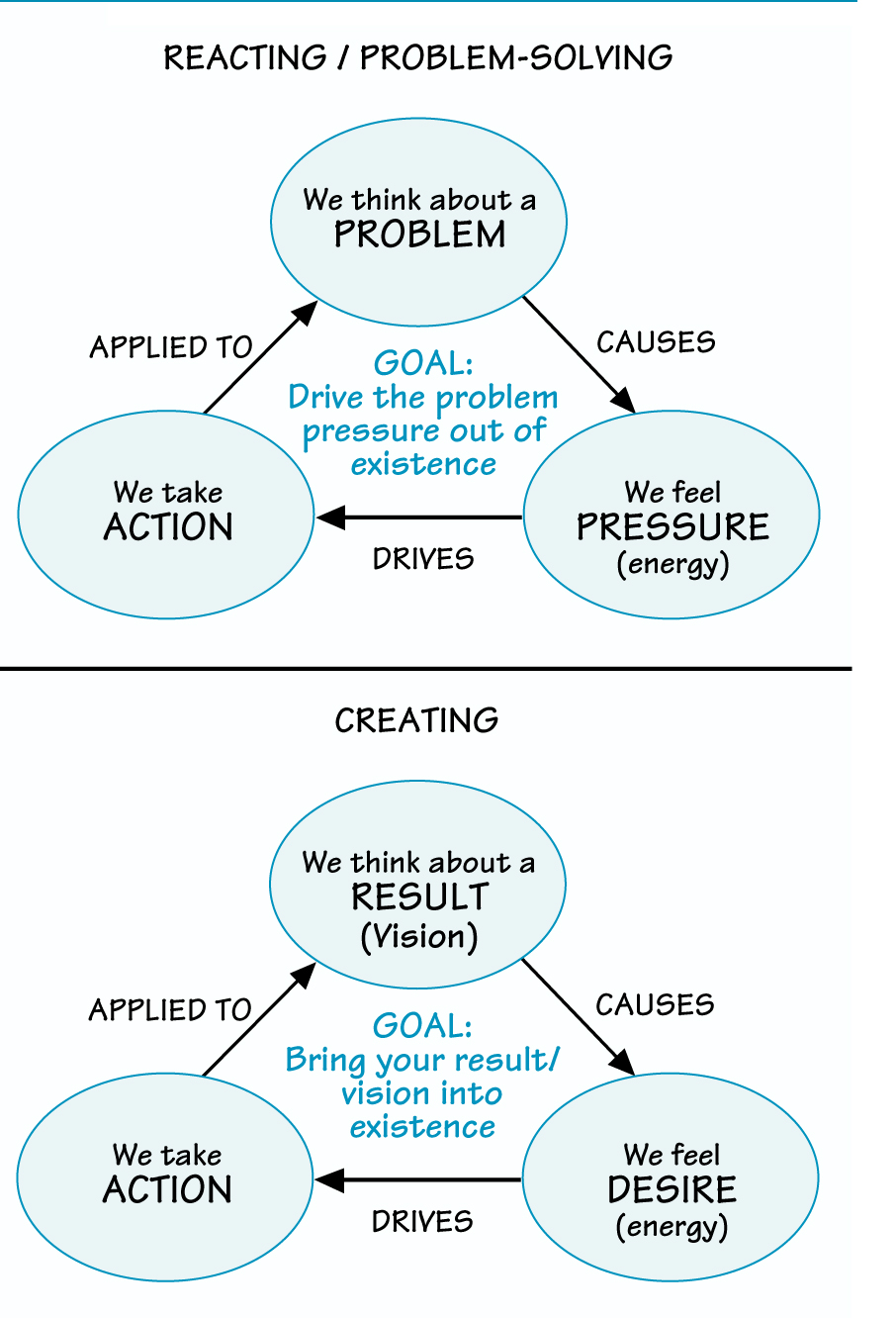

The discipline of personal mastery helped me move from reacting to creating my way through life. As I studied the concept of the creative versus the reactive orientation, as articulated by Robert Fritz in The Path of Least Resistance: Learning to Become the Creative Force in Your Own Life (Ballantine, 1989), I realized that there are two kinds of energy that prompt people to take action: pressure or desire. As a knower, my energy came from pressure, so I always operated from a reactive (problem-solving) orientation. I came to understand that there was an alternative to living my life on the problem-solving treadmill, and that was to bring new things into existence (see “Reacting vs. Creating”).

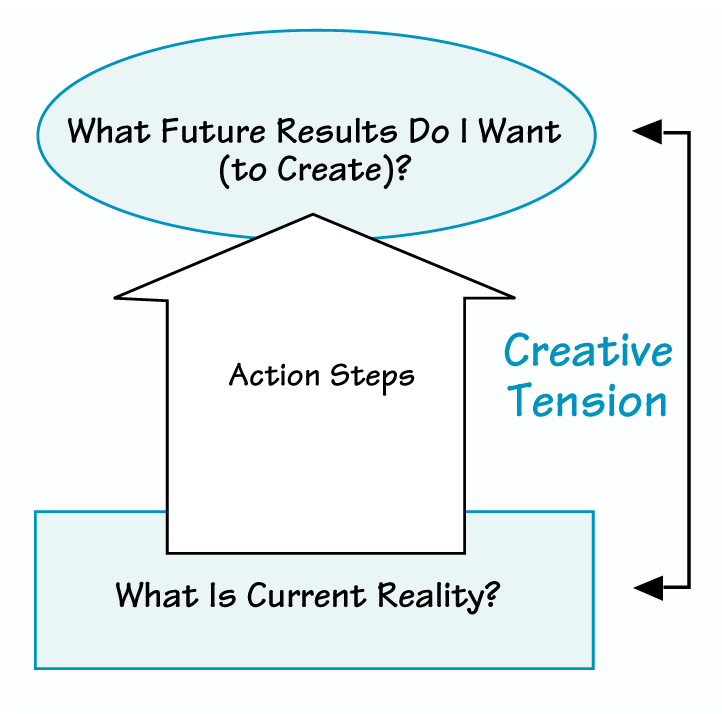

I became interested in this new framework but had no idea how to go about living from a creative orientation. Fritz’s creative tension model gives structure to the ethereal idea of bringing something new into existence. Creative tension juxtaposes an honest and accurate awareness of current reality with a precise mental picture of your vision or the desired results you want to create (see “Creative Tension Model” on p. 6).

Knowers have a hard time looking at current reality when the results are inadequate and they have some responsibility for them. The concept of creative tension helped me see less than-desired results as just one part of a larger scheme of success.

REACTING VS. CREATING

Shared Vision

Groups operate more effectively when they are aligned around an idea or goal. As I progressed in my knowledge of shared vision, I moved from using a short-term compliance strategy to a long-term commitment one.

The compliance strategy can work, but only for a short while. Four conditions are necessary for employees to feel a sense of dedication to a future direction or desired result: (1) Access to valid and relevant information; (2) Free, informed choices from a series of alternatives; (3) Participation in discussions and decisions; and (4) Alignment of the chosen direction with personal vision and values. If any one of these elements is missing, people will feel manipulated, their trust will be diminished, and their commitment to the decision will plummet.

These four conditions spread control among the members of the group, rather than maintaining it in my hands alone. This is a difficult transition for knowers to make. I must move from having “control over” to having “control with” others. However, breaking the commitment strategy down into four elements is very comforting for a knower—I can get my head around it.

Mental Models

The essence of the discipline of mental models is moving from having conversations in “protection mode” to having them in “reflection mode.” In protection mode, I believe that I must protect the “fact” that I am right, that I have all the information I need, and that I have not contributed to the problem. In reflection mode, I ponder my thinking and actions and ask questions such as “Why did I react so strongly just now?” “What information am I missing?” and “Have I somehow contributed to this problem?”

CREATIVE TENSION MODEL

Using Robert Fritz’s creative tension framework, learners juxtapose an honest awareness of current reality with a precise mental picture of the results they want to create. By doing so, they are able to identify the actions required to move from current reality to the desired future state.

Operating in reflection mode is a huge leap for knowers to make. Knowers feel they must protect what they know — they can’t be wrong or have incomplete knowledge. However, through the discipline of mental models, I have come to admit that there are multiple views on a given subject and that these other views can be valid and rational, too. When I was introduced to concepts such as “left-hand column,” “ladder of inference,” and “learning conversations,” I discovered a way to understand how people think and interact. This is great information for a knower! It takes some of the mystery out of difficult conversations.

Systems Thinking

The essence of systems thinking is moving from focusing exclusively on “the parts” (especially my part) to focusing on “the whole.” As a knower, I focus on “my part” because it is knowable, controllable, and containable, and I pride myself on my ability to address problems. But what if the cause or effect of a problem does not fall within my realm of control? If I pride myself on problem solving, I had better be able to fix this problem. But because I have focused exclusively on my area, I really don’t know how to go about addressing it. Should I admit that I don’t actually know all about my area after all or that I really can’t solve this problem because it falls outside my realm? I can’t be both an expert in how to run my area and a problem-solver extraordinaire when a cause or effect of a problem falls outside of my domain.

The essence of team learning is developing an ability to move from debating who has “the truth” to generating collective insights together.

The solution to this dilemma, I found, was to broaden the scope of what I pay attention to beyond my little piece of the world. I need to focus on “the whole” rather than just “my piece.” Systems thinking tools and principles help in this regard.

Team Learning

The essence of team learning is developing an ability to move from debating who has “the truth” to generating collective insights together. When I debate, I am pursuing the right answer — the correct answer. I am talking about things I know. Within the realm of what is actually knowable, this can work well. We run into trouble, however, when what is “known” becomes outdated and obsolete as the world continues its rapid change around us. Therefore, I gradually recognized that it is necessary to generate new insights in order to make progress. I just had to find a way to do so that wouldn’t threaten me.

I was exposed to a conversational technique called “dialogue,” which is often used to generate collective insight. When I began to try it out in groups, I realized that, at a certain critical point, there is, literally, nothing to debate. We are seeking “emerging knowledge,” which are ideas that have not yet fully emerged. It is impossible to debate who has the “right” emerging knowledge. When new ideas are being revealed, there is no debate.

Team learning does have some attractive and practical qualities for knowers. Knowers are always interested in uncovering new things that can be “known” — they just have to overcome their hesitancy to accept them if they come from someone other than themselves. Dialogue can also be employed as part of a problem-solving process, but it should not be used for making any final decisions — dialogue must precede decision-making. In addition, team learning is a great way to introduce collective responsibility to a group (“how did we each contribute?”), which is particularly attractive to knowers, who are very sensitive to being blamed.

Learn, Unlearn, Relearn

Alvin Toffler wrote, “The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.” Can you imagine the day when people’s competence is based not on their ability to be knowers, but on their ability to learn, unlearn, and relearn? Will you be ready? Will you be “literate”? By understanding the pitfalls of being a knower and diligently practicing the five disciplines, you will place yourself squarely on the path to success in the 21st century.

Brian Hinken (bhinken@gmhs.org) serves as the Organizational Development Facilitator at Gerber Memorial Health Services, a progressive, rural hospital in Fremont, MI. He is responsible for leadership development, process facilitation, and making organizational learning tools and concepts practically useful for people at all levels of the organization.