Storytelling has been around since the dawn of civilization (in fact, as we’ll see, it may have been the first glimmer of light at that dawn). So why is it now such a hot topic in communications circles? What makes one story resonate with us, even after many years, while another almost instantly becomes yesterday’s news? How do stories reveal truths we normally hide from ourselves? Finally, how can those of us committed to bringing about positive change — either corporate or political — use the power of story for the common good?

This article deals with these questions and many more. We’ll be using insights ranging from the latest research in cognitive psychology to recent scholastic discussion about the pre-Socratic Greek philosophers. And we will present a story model, known as PHAAT (for Passion, Hero, Antagonist, Awareness, and Transformation), that we developed after years of working in the world’s most story-centric corporations — the entertainment industry. But before we do, we’d like to tell you a story:

A senior vice president from a Fortune 50 energy conglomerate recently contacted us. Let’s call him John B. John was the type of client we love to work with. He had just left a high-level position in his company’s petroleum division and moved to a new division focused on alternative fuels.

John wanted to make a difference and he had a problem. He needed to give a presentation at a government conference on alternative energy policy. His audience would consist of competitors, government regulatory agencies, and environmental watchdog groups. His talk was titled “Developing the Hydrogen Economy Infrastructure.”

Some in his audience were technical experts; others knew almost nothing about this particular subject. An engineer and chemist himself, John was concerned that his presentation might prove too dry and technical. He told us he had two goals. One was his corporate mandate: to turn competitors into collaborators in what would prove to be a multibillion-dollar investment in R&D. The other was personal: to impress his boss. We suggested he use the power of story.

Storytelling’s Genetic Roots

Why story? First, because telling stories is what we do best, and second, because as cognitive psychology is proving, narrative is the most powerful way humans have to communicate and remember information. It is something we all do all the time. In fact, according to some scientists, storytelling may be hardwired into us, perhaps through a gene called FoxP2.

Discovered in 2001 by Anthony Monaco and his research team at Oxford University, FoxP2 is now thought to be only the first in a constellation of genes that make language and narrative possible. FoxP2 specifically enables the subtle physical and neurological skills needed to speak words rapidly and precisely; it is probably linked to the use of complex syntax as well.

Linguists have argued for years about when and where language began. With the specific genetic marker of FoxP2, scientists at the Max Planck Institute began to look for a date in the DNA record. Through statistical analyses, they determined that the characteristics of the FoxP2 gene that support sophisticated articulation of speech likely occurred within the last 200,000 years.

That date is significant, because around 50,000 years ago, there was an explosion of knowledge worldwide. Humans moved off the plains of Africa and into Eurasia, beginning the migrations that would eventually populate the entire globe. Hunting became more complex and productive; tools became much more specialized; the first signs of trade were seen; ritual burial started; collaborative cave paintings appeared; and what we think of as “culture” was born. Archaeologists can trace the paradigm shift from valley to valley.

Animal-1

Animal-2

Some scientists assert that this sudden, accelerated advancement in technology, art, and commerce is attributable to humankind’s newly found ability to retain and convey complex knowledge in the form of stories. As evidence, they point to the fossil record, which shows that human physiology remained the same during this period of vast cultural change. Some have advanced the hypothesis that the cultural changes were the direct result of the spread of the enhanced FoxP2 gene.

Dr. Savante Paabo, who led the Max Planck team, speculates that the changes to FoxP2 spread so rapidly because they gave humans a survival advantage; he said, “Perhaps by singing more beautifully, or by spinning more engaging stories, they were more sexually attractive.” However it happened, the mutations to FoxP2 spread so quickly that now everyone has them. From a cellular level on up, we are all born storytellers.

From the Mouths of Babes

To understanding the ubiquitous power stories have in organizing our experience, all we need to do is look at children. In the winter of 1968, Jerome Bruner, one of the founding fathers of cognitive psychology, was at the Harvard School of Education’s experimental nursery school observing the behavior of 9 to 18 month-old children who did not yet have the ability to speak. As Bruner watched and interacted with these babies and toddlers, he realized they were doing much more than enjoying random play. They were organizing their lives into stories with plots, characters, and themes. Even before they learned language, they had developed sophisticated stories with distinct points of view, obstacles to overcome, and new awareness and transformations. In fact, Bruner concluded that children are motivated to learn language because they already develop powerful stories that they need to communicate to the people who inhabit their world.

Bruner observed that young children develop different kinds of stories — stories of completion, stories of concern, and stories of pleasure. The young child says (by means of gesture and facial expression) “All gone” when her bottle is empty, “Uh oh” when she feels she has made a mistake, and “Ohh!” when she is surprised or pleased.

These stories are short but complete, and they meet the definition we have developed: Stories are facts, wrapped in emotions, that compel an awareness with which we transform our world.

Take the story, “All gone.” The fact is that the bottle is empty. The baby wraps this fact in an emotion either satisfaction or desire for more that she expresses. Depending on which emotion is expressed, the parent becomes aware of the situation and takes an action either burps the baby and settles her down, or refills the bottle. Either way, the baby has transformed her world for the better. Brunner went on to assert that infants develop meaning through narrative and that the need to create stories precedes language itself.

Thus, story is not simply the content of what we think, it is the how of how we think. It is one of the key organizing principles of our mind.

Five Key Elements

So if story is something innate in each of us, something we all know how to do, why are some of us so much better at it than others? Why are some stories so powerful and compelling that they lead to change, while others fail to have an impact?

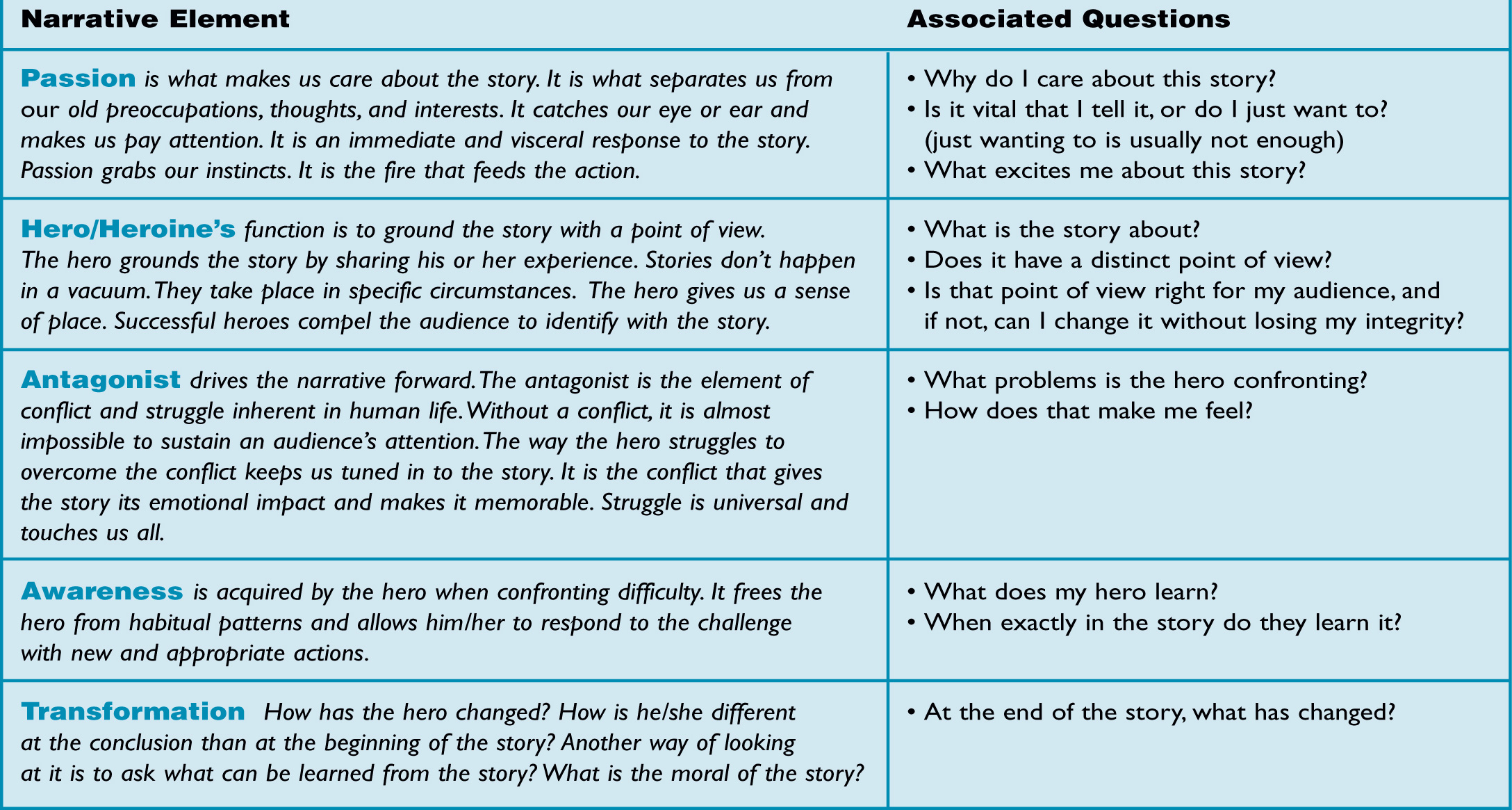

A NARRATIVE SYSTEM FOR LEADERSHIP

Having spent the bulk of our careers in the entertainment industry (as actor, writer, producer, coach), we have dealt with literally thousands of professionally crafted stories and have come to realize that successful stories contain five key elements. They are told with Passion and vitality. They have a clear point of view most often expressed as a Hero. The hero confronts an Antagonist or overcomes obstacles, and in this process gains new Awareness with which he or she Transforms the world. To make it easy to remember, we call this narrative process PHAAT (see “A Narrative System for Leadership,” p. 3).

Why five elements and not, say, six or seven? To answer, we need to take just a short hop back in time (then we promise to return to our story about John B. and hydrogen technology).

Since culture is transmitted from generation to generation through story and fable, it is not surprising that the key to understanding how story is structured as a communication system would lie at the beginning of our own culture. Pythagoras was the first great systems thinker in Western culture. Unfortunately, he left no writing behind. So our study begins with his student, the philosopher and poet Empedocles.

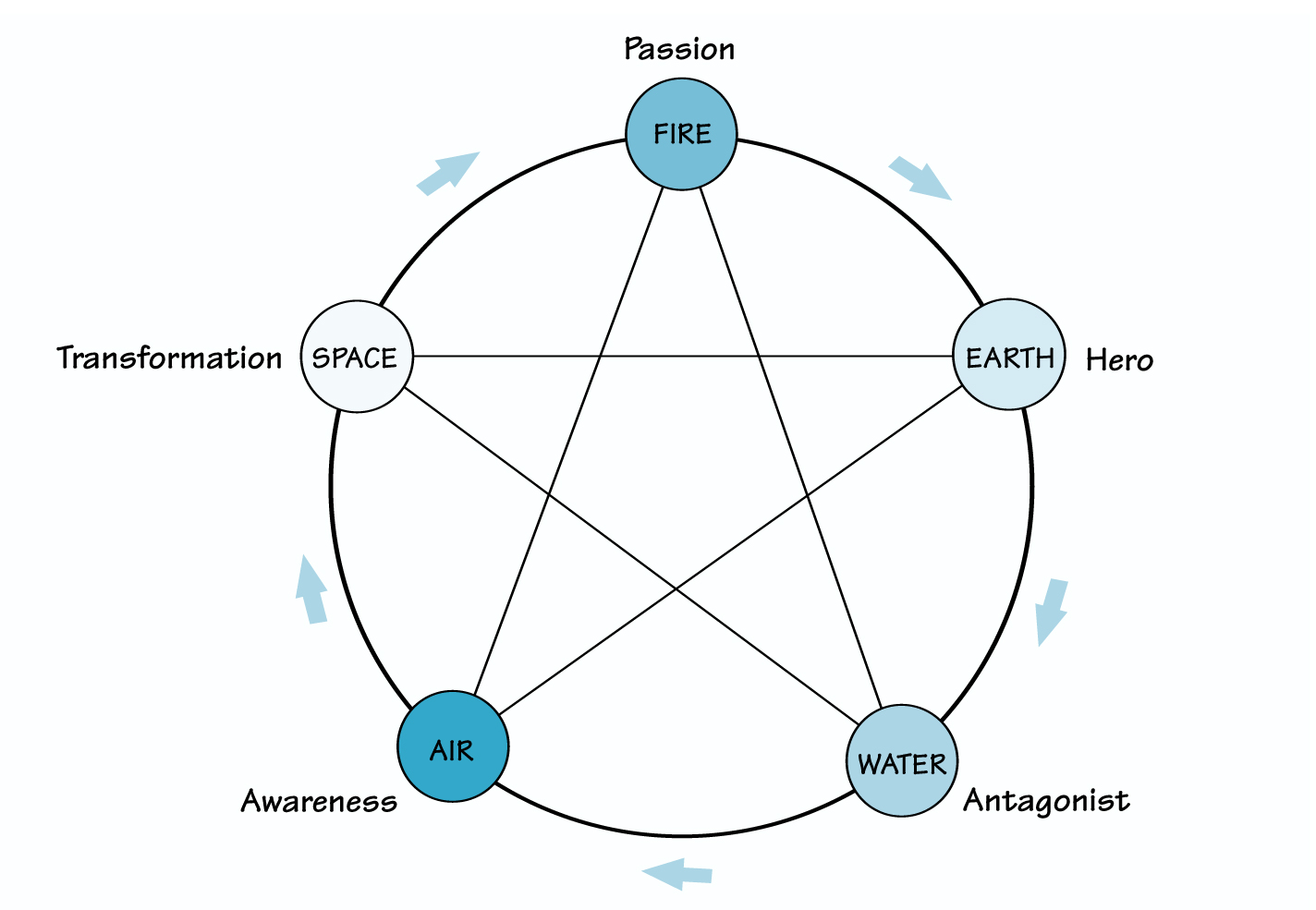

From Empedocles, we first get the concept of the world being made up of four elements: Fire, Earth, Water, and Air. A fifth element, implied by his theory but unstated, was added a generation later by Plato and his student Aristotle. Sometimes called “Ether,” this fifth element is perhaps more accurately referred to as “Space,” because it is the field in which the other elements occur.

Until recently, conventional wisdom viewed Empedocles as a natural philosopher in essence, a proto-scientist primarily trying to describe the material world. More recent scholarship (by Pierre Hadot, Peter Kingsley, and most preeminently by contemporary philosopher Oscar Ichazo) has shown that the four elements of Empedocles were not solely material but also described inner psychological states. Empedocles considered these elements divine, because he saw them as part of the eternal nature of consciousness itself.

ELEMENTS OF A SUCCESSFUL STORY

In that archetypal psychological sense, Empedocles’ elements relate to our understanding of story. They are keys that allow us to see narrative holistically, with each element contributing its own unique quality to the overall system of the story. The image of these elements is so deeply engrained in our culture that we intuitively understand what each contributes to the whole and how they interact. Ichazo goes so far as to call the elements “ideotropic,” in the sense that they are ideas that attract our mind to an inner truth in the same

Every powerful narrative vibrates with passion, the energy that makes you want, even need, to tell it.

way that a plant is attracted to the sun. We often refer to these elements as a way to help people see story as not just a product of language, but as the expression of something deeper and even more powerful (see “Elements of a Successful Story”).

PHAAT Stories

So how do the five archetypal elements of Empedocles and Plato relate to the narrative elements of PHAAT?

There is a direct correlation, which brings us back to our story.

When John B. came to us with his problem, we did what we always do: We listened to his story. We asked him, “Why did you leave the most stable and secure division of your corporation — petroleum — and move to an alternative fuel division that is still experimental?”

John responded by saying he wanted to make a difference. He told us about the places he had visited in his life, places of great natural beauty that he feared would not be there for his children because of global warming. John told us that he honestly felt that the project he was involved with — the development of a hydrogen alternative to fossil fuels might be a big part of the solution. And as a businessman, he was convinced there was real money to be made by being part of the solution rather than part of the problem.

Passion

John’s recounting had the first element of any successful story: He had passion. Every powerful narrative vibrates with passion, the energy that makes you want, even need, to tell it. It is the essential spark, the irreducible cohesive core from which the rest of the story grows. Passion relates to Empedocles’ element of Fire, in that it ignites the story in the heart of the audience. It is passion that calls the listener’s attention in the first place, particularly if the story is aimed at more than one person.

Every audience is composed of separate individuals with differing needs, desires, and distractions. Theater people call such an audience “cold.” They know it needs to be “warmed up” before it can absorb new material. That is what passion does: It kindles our interest and makes us want to hear more.

In any given situation, you either have passion or you don’t (although sometimes people simply need help finding it in their story and being comfortable expressing it). John B. had it. It was easy for us to guide him in molding his passion into a warm and welcoming message that served as a gateway into his presentation.

Hero

All the passion in the world won’t do your story any good unless you have someplace to put it. That is where the hero comes in. The hero relates to the element Earth and, as such, grounds a story in reality and gives it a clear point of view. By hero, we don’t mean Superman or a grandmother who rushes into a burning building to save a baby, although these are examples of heroes. We mean the story’s POV (point of view). The hero that embodies this point of view needs to be substantial enough to give the story “a leg to stand on,” but also of a scale that allows the audience to identify with him or her. The hero is both our surrogate and our guide through the narrative. His or her vision of the world creates the landscape our story inhabits.

One of the things that made John B. such a good hero was that he was willing to take a stand and express his point of view. Many in the corporate world find doing so very threatening. They have been trained for years in corporation speak, hiding behind the corporate “we.” In some cases, this distancing is appropriate. But when you are going for the gold, you have to embrace what you are saying and let the audience see it through your eyes.

Being a hero requires courage. If you passionately believe in what you are saying, you will find you have the courage to communicate it. Here are a few simple cues for making an impact:

- Remember the ground you are standing on (if you are speaking to a group).

- Remember to be specific (if you are communicating in writing).

- Remember to connect your thinking to the big picture (a hero conquerors the world, not just the front yard).

We always ask, “Can other people identify with this story? Is it the right story for this audience? Does it have a point of view they will be willing to share?” John’s story did. We have all seen things in our lives that we want to protect. We all want to leave our children a better world. Expressing this kind of point of view makes you a hero, too.

Antagonist

Problems are like Water — without them, a story dries up and blows away. In stories, problems are often personified by an antagonist. Antagonists, and the conflict they represent for the hero, are the beating heart at the center of the story. By antagonist, we mean the obstacle the hero must overcome. The antagonist doesn’t have to be a person — if the hero is struggling to climb Mount Everest, the antagonist might be the mountain itself — but every successful story must have at least one. If the hero faces no obstacles, there really is no story. It is the struggle to overcome impediments that creates the story’s emotional reality.

The hero is struggling to climb Mount Everest

Stories often personify conflict as a villain, someone we love to hate. Two time Academy Award winner William Goldman says you only need to answer three questions to start a good screenplay: “Who is your hero? What does he want? Who the hell is keeping him from getting it?” This is the technique Goldman uses to help find and define conflict. The Dalai Lama, who won the Nobel Peace Prize for his understanding of how to deal with international conflict, put it in more universal terms: “Each one of us has an innate desire to seek happiness and overcome suffering.” He also said, “Your enemies are your best teachers.”

Great stories mirror this reality. Such tales are fun because, instinctively, humans are interested in how others deal with their problems. A narrative is compelling and memorable when it wraps emotions around facts to engage a listener’s curiosity. Research, including high-tech, real-time brain scans, is now showing that emotions, triggered in the limbic area of the brain, are what lock a story in memory (Antonio Damasio, The Feeling of What Happens, Harcourt &Brace, 1999). Discovering the emotions underlying a message is an essential step to releasing a story’s power.

John B.’s project, developing a hydrogen energy infrastructure, faced tremendous obstacles. His company was literally proposing to restructure the primary transportation system for a large portion of the planet. The initiative posed tremendous technical, political, and economic difficulties, and a lot was riding on it.

John’s talk carefully delineated each potential problem. As he offered specific avenues by which these obstacles might be overcome, his audience became more and more emotionally committed to the project. They liked his idea and wanted it to succeed.

Awareness

So what allows the hero to prevail and overcome a daunting obstacle? In great stories, it is a moment of awareness. This flash of inspiration lets the hero see the problem for what it is and take the right action.

There is something magical about these “aha” moments. Like Air, they are almost impossible to get your fingers around. Awareness is not always easy or comfortable, but if you want your stories to make a difference, something needs to be learned.

John B. and his company had learned that no single corporation or government could accomplish the goal of developing hydrogen fuel alone, especially in the crucial time remaining before we reach the global warming tipping point. Collaboration is our only hope. And as John was careful to point out to his corporate competitors, the shift to a hydrogen economy is potentially enormously profitable. All it takes is seeing the opportunity and seizing the moment becoming aware of the problem and the promise. John and his corporation were more than willing to share the wealth with others.

Transformation

Transformation is our last story element; it corresponds to Space. If you’ve taken care of the other elements in a story, it just naturally happens. Our heroes take action to overcome their problems; as a result, they change, as does the world around them. Change is the playing field (the space) on which stories are told. Like a playing field, stories contain goal posts, and the audience feels satisfied when they see their hero overcoming obstacles and scoring big.

So how did our hero, John B., do? How did he transform his world by telling his story? As a result of his 20-minute presentation, he was approached by representatives of four other major players in the energy field who wanted to explore the possibility of strategic partnerships. John’s boss liked the speech so well that he sent John to Davos, Switzerland, to present it to that year’s convocation of world thought leaders a move that doesn’t hurt anyone’s career path. But most important, John’s project for building a hydrogen economy infrastructure, which we think really might be a big part of solving the problem of global warming, is moving full speed ahead.

Fine-Tuning Your Story

If your story is weaker in one area than in another, then work on the weak element. For example, you feel very powerful emotions about the scientific facts underlying global warming, and you think you know the solution, but you’re not able to provide the audience with a point of view than allows them to feel comfortable accepting those facts. As a result, they find your story, well, science fiction. What your story needs is a good hero. A hero your audience can relate to and accept as authentic and whose problems mirror their own. It shouldn’t be hard to find one. There are plenty of heroes out there, and once your story has a good one, it will be grounded in the experience of your audience and easily accepted and understood.

Or let’s say you are giving a presentation to an interdepartmental meeting within your corporation. You’ve carefully marshaled your facts so each department can see what relates to its particular interests. You’ve laid out the steps needed to overcome the obstacles ahead. There is no doubt the overall result will be a positive transformation.

But you finish speaking and notice a distinct lack of interest in your audience. You think you may have even seen your boss stifle a yawn. Your problem may be that you haven’t connected your passion to your presentation.

Remember, according to our definition of story, it is emotion that makes facts compel people to take action. You need to ask yourself why you care about the project you are suggesting. What feelings does it bring up? If you find your own emotional anchor to the project — why you want to suggest it — and can be open and honest about those feelings without histrionics, that passion will transmit to your audience. At the very least, it will provoke a heated discussion of the topic. With passion, your presentation will fire your audience up, and that beats cold stares anytime.

Of course, story-telling is an art, and no one element of the PHAAT paradigm can ever be considered in total isolation. For example, you might have problems connecting to the passion of a story because you really don’t feel comfortable with the transformation it produces. Analyzing problems in corporate communication requires subtlety and experience, but the PHAAT model and its grounding in the five elements of the ancient Greek philosophers is an excellent place to begin.

Like John B., your story will be remembered — and make a difference if it contains the five essential PHAAT elements.