Managers in many companies slay are struggling with one basic question: How do you actually create a learning organization? While the five disciplines described by Peter Senge in The Fifth Discipline (Doubleday, 1990) provide a conceptual framework for organizational learning, the connection between the goal of creating a learning organization and the actions needed to achieve that goal have remained tenuous.

Part of the difficulty stems from the fact that organizational learning, like company culture, is controlled only indirectly by those in charge of the organization. The management levers that drive organizational learning are numerous, spread throughout the organization, and often work only after substantial time delays. And since every organization is unique, the levers that will enhance learning vary from company to company. As a result, it is difficult to identify a single action plan for building organizational learning capability. Instead, what is needed is a set of guide-posts that can help managers identify their own learning objectives, evaluate their current capabilities, and create a customized plan to move toward those goals.

The Organizational Learning Inventory

The Organizational Learning Inventory is an assessment tool that helps managers identify specific actions that can promote organizational learning in their company (see “Organizations as Learning Systems,” October 1993). This tool addresses the questions: What can we do to improve our organization’s ability to learn? How can we create an integrated strategy for learning? And how can we assess how well that strategy is working?

The cornerstone of the Organizational Learning Inventory is a framework of ten Facilitating Factors and seven Learning Orientations (see “The Organizational Learning Inventory” on page 3). Facilitating Factors are those activities or attitudes that promote or inhibit learning (e.g., environmental scanning or an experimental mindset), while Learning Orientations describe stylistic differences in the ways companies approach learning (e.g., focusing on breakthrough learning versus incremental improvements). Together, these Facilitating Factors and Learning Orientations describe an organization’s overall learning system. By using the Inventory, managers can better assess their company’s learning capabilities and develop a plan to manage their learning processes more explicitly.

The management levers that drive organizational learning are numerous, spread throughout the organization, and often work only after substantial time delays.

The Inventory is not meant to be simply filled out and tabulated in a report. It is most effective when used in a work session that engages a group in identifying their company’s specific learning objectives and analyzing the organization’s barriers to learning. The real value of an Organizational Learning Inventory Work Session thus lies in the quality of conversation it promotes, which can lead to shared mental models and a shared learning strategy. The more specific and “actionable” that strategy is, the more likely it is to succeed.

Steps in a Work Session on Organizational Learning

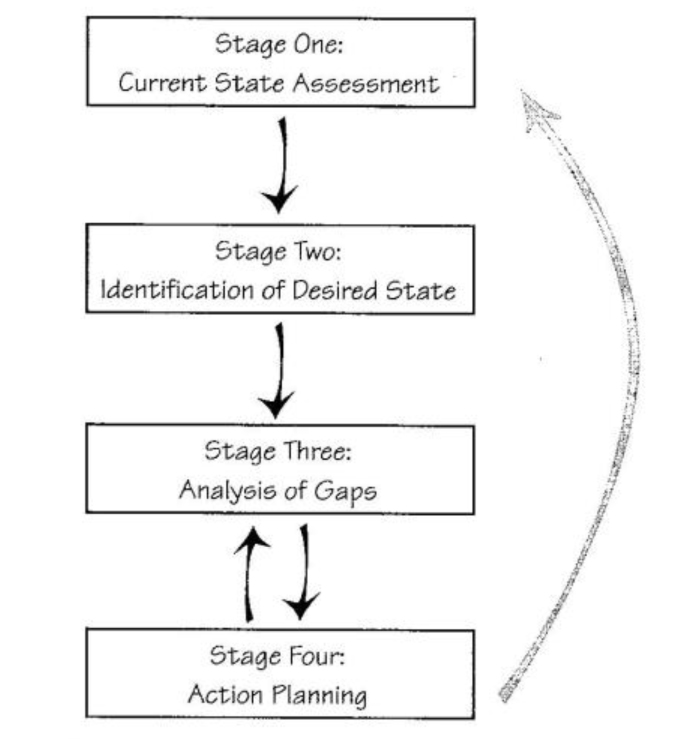

The Work Session consists of four stages, from assessing the organization’s current learning capabilities to creating an action plan to meet the company’s learning objectives (see “The Process”).

In the first stage, participants address the question, “Where does our organization fall along the dimensions identified in the Inventory?” As each criterion is introduced, the participants evaluate the organization’s capability or preferences in that area. For example, as they discuss the Facilitating Factors, group members may rank how much evidence there is that the company is investing in activities such as determining performance gaps, involving leadership in learning initiatives, and promoting continuous education. The current state assessment is best accomplished in a focus group or working session, rather than through surveys or interviews, because this gives the team an opportunity to develop a shared understanding of the company’s learning strengths and weaknesses. The dialogue that emerges from the assessment helps create momentum to make the transition from generic guideposts to organization-specific action steps.

After the current state assessment is complete, attention turns to exploring the desired state (stage two). At this point, the participants discuss the learning capabilities they think will be necessary to support the organization’s strategic business objectives. The group can use the Learning Orientation section of the Inventory to explore the company’s particular “style” of learning, and to consider how the company’s unique strengths can be used as a source of competitive advantage.

Once the group has laid out the company’s current capabilities and learning objectives, it then assesses the gaps between the two (stage three) and develops an action plan to close those gaps (stage four). One possible approach is to simply go through each dimension, look at the size of the performance gap, and determine an action strategy to reduce or eliminate the gap. But since it is likely that performance gaps will exist along several of the Inventory dimensions, such a process might become overwhelming. Instead, it may be more useful for the group to focus its efforts on the three or four most critical areas, and develop action plans to address those gaps. Over time, as the team makes headway on these initial issues, the focus may be drawn to other gaps.

Learning about Learning: The inventory in Action

Just as Royal Dutch/Shell discovered through its “planning as learning” process that the act of creating a plan can be more important than the actual plan, the Inventory is of value to decision-makers because of the assessment process, not because of the tool itself. This was the experience of a group at the Harvard Law School Library, who used the Inventory to create their own learning strategy.

The Process

An OLS Work Session consists of a four-stage process: (1) assessing the company’s current capabilities, (2) identifying the learning objectives, (3) analyzing the gaps, and (4) creating a plan to move toward those goals.

Harvard Law School Library (HLSL), with its staff of 90 employees, faces several strategic challenges in the next few years. Beginning with the June 1996 commencement, HLSL will close its physical plant for 14 months while the entire facility is renovated. In the process, the staff must move an inventory of 1.7 million volumes of legal information and somehow continue to provide services and limited access to a demanding faculty and student body.

In addition, HLSL is facing the same challenges as other research and professional libraries, as technology transforms how they maintain their assets and provide access to them. In fact, the very definition of an “asset” is changing. It is beginning to include electronic records, databases, and other multimedia information, as well as books and other traditional media. As a result, the concept of “access” is also changing — from physical location and retrieval to electronic access via networks. Along with this comes the need to train the library’s patrons how to make the best use of these electronic tools.

Terry Martin, professor of law and librarian of the Law Library, was visionary enough to recognize the parallels between the short-term challenge of the renovation and the long-term strategic shift required by the technological changes. The question he saw the library facing was, “How can we use our physical renovation as a laboratory for learning how to provide our services in this new ‘virtual’ marketplace of legal research?” To address this issue, he and his staff used the Inventory to develop “A Framework for Learning”—their own customized learning strategy that will help them prepare for the future.

The HLSL Experience

The first step in the HLSL Work Session was to invite all members of the Library’s staff to a brief introductory session to discuss the concepts of organizational learning and the process of using the inventory. To assist in this process, books and articles on organizational learning were also made available through the administrative offices.

Next, they recruited a solid cross-section of interested staff members to participate in the Work Session. In particular, the assessment-to-action nature of this process made it especially important to include those individuals who were most interested in, and able to assist in, implementation. This broad representation had the added benefit of helping to educate newer staff on how other departments conduct their operations.

Over the course of one week, HLSL worked through the Inventory in five groups — four cross-departmental teams of four to five staff members, and one leadership team. Later that week, all of the participants came together to review their assessments and share key pieces of their visions for where the Library will be in the year 2005.

In the ensuing conversation, they focused specifically on “weak links” in HLSL’s capabilities, the impact of changing trends in library research, how their preferred learning style as a group might need to change to reflect these trends, and the key leverage points that would help them make significant changes in their learning profile. For example, they recognized the need to continue to break down traditional functional barriers by sharing critical information across boundaries. In addition, they articulated the need for strong leadership to set priorities, and they acknowledged how they could enhance their problem-solving if they took other perspectives into account.

From this discussion, the HLSL group identified four key “fields” or characteristics from the Inventory on which to focus their “Framework for Learning”:

- Involved Leadership (to transform vision into action)

- Formal Dissemination (to ensure the rapid and consistent dissemination of important information)

- Team Learning (to move from a traditional focus on individual skill-building to becoming skilled at working in teams)

- Systems Perspective (to break out of traditional functional perspectives).

Establishing Goals and Objectives

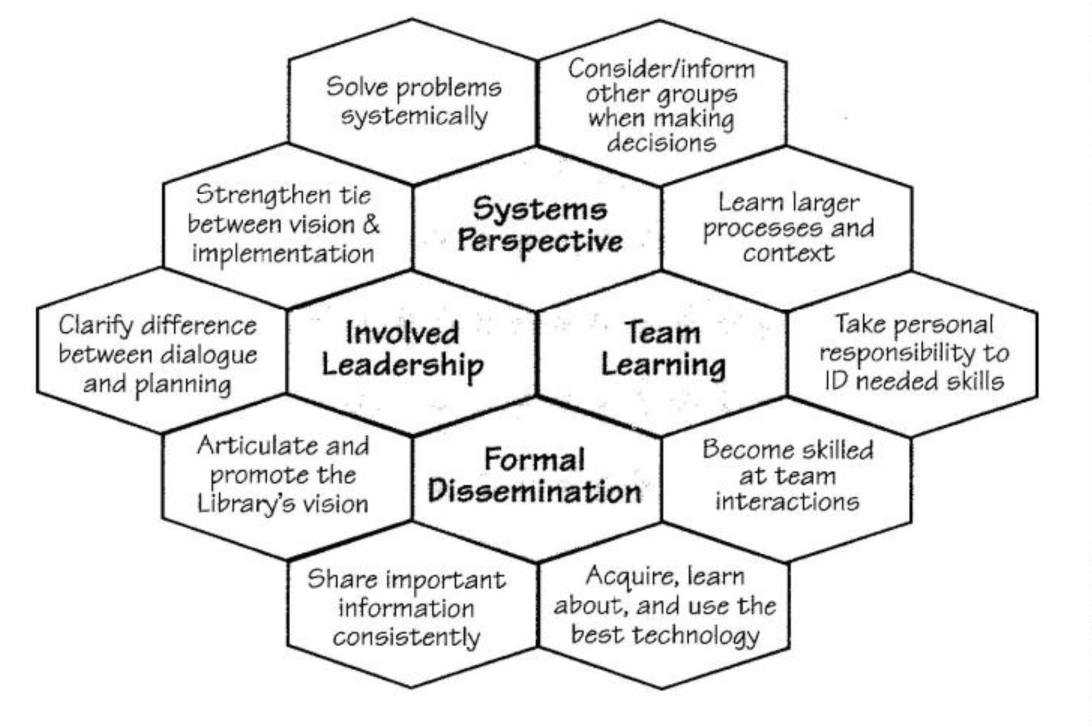

Rather than proceeding from the key goals to a linear set of objectives, the Library staff used graphical facilitation to creatively explore the relationships between these four goals, to see what larger issues might emerge. For example, pairing “Team Learning” and “Systems Perspective” drew out “learn larger processes and context” as one objective. Through this work, the group developed a cluster of larger objectives surrounding the four goals, which included “become skilled at team interactions,” “share important information consistently,” and “strengthen tie between vision and implementation” (see “Relationships between Key Goals”).

This cluster will become the ground from which, twice a year, a rotating team of volunteer “organizational learning stewards” will identify a new set of commitments for each of the three groups at HLSL: the institution, the working teams, and the individuals. For example, one commitment asked of the institution is to “reinstitute orientation training and materials to give new staff members an understanding of the fundamental processes and goals of HLSL, and to give experienced staff up-to-date information about who is responsible for what information and processes.” For working teams, the initial plan calls for participants in departmental meetings to ask, “Who else is involved in this issue? Who else needs to be informed about our plans?” And individuals are asked to “take responsibility to identify skills that I will need [next year] and get them included as part of my annual performance review this spring.”

In order to keep the process fresh and manageable, the team will throw out each set of commitments after six months and create a new list from the goal cluster, asking themselves, “What are the best things we could do now to accomplish these goals?” If a previous commitment makes it back onto the list, it will be because it remains a significant element of HLSL’s learning strategy. This ongoing process is a self-generated, self-renewable learning strategy based on an assessment that is specific to HLSL’s unique situation and needs.

Aligning Corporate Strategy with Learning Strategy

Developing an organization’s learning capacity requires a broad base of support and understanding. When the HLSL project started, some members of the staff were curious about organizational learning, and several people even had a vague notion of what organizational learning meant, but they had no real idea about how to begin. Within a week, however, the Library staff had developed a learning strategy that reflected its current strategic situation, and its employees had discovered for themselves the value of using a systemic perspective to plan and solve problems.

As the HLSL story illustrates, one of the greatest values of the Organizational Learning Inventory is the explicit link it creates between an organization’s learning strategy and its overall business strategy. Creating a set of learning initiatives that will support future activities and create a competitive advantage is a major innovation at most organizations. For example, the very fact that a management team may conclude, “We need to invest in scanning our environment” represents significant progress in an organization’s strategy for learning.

In most cases a team will likely discover that their company’s business strategy suggests a specific learning path. That is, for a given Learning Orientation, they might find that their business strategy calls for positioning the company at a particular place along the spectrum. Or their business strategy may call for particular emphasis on some Facilitating Factors over others. At HLSL, for example, the renovation and the changes in technology required a radical shift in orientation from individual toward team learning.

As the team discusses how the business strategy translates to each dimension on the Inventory, both the business strategy and the learning strategy become clearer and the link between them is made increasingly explicit. In fact, because the Inventory provides a concrete framework for what has historically been one of the “softer” components of an organization’s strategy, the discussion surrounding the future state of learning capability may lead to a refinement in the business strategy.

Together, strategy and organizational learning cover a lot of conceptual ground. Some teams may be fortunate enough to have access to someone who is knowledgeable about both strategy and organizational learning, but generally this is not the case. Most will have to forge ahead and bridge the gap on their own. With practice and a clear set of guideposts, however, a team can develop the skills necessary to align its learning objectives with its business strategy.

Marilyn Darling is an associate at GICA Incorporated and also a principal of Signet Consulting Group. Gregory Hennessy is an associate at GKA Incorporated. They are both certified facilitators of the Organizational Learning Inventory.

Editorial support for this article was provided by Colleen P. Lannon.

References: Arie deGeus. “Nanning as Learning,” Harvard Business Review. Mar-Apr 1988.

Relationships between Key Goals

The HLSL team grouped their four goals into a cluster and then explored the relationships among them In order to Identify the larger themes and Issues. This duster will become the basis from which, twice a year, a rotating team of “organizational learning stewards” will Identify a new set of commitments for achieving HLSL’s learning objectives.