This is the tale of a powerful, synergistic confluence of process and technology at a three-day strategic conversation last December that moved two large companies closer together. When planning for the event began in the late spring of 2005, no one could predict how it would turn out and whether the gaps between the two partners could be closed. The handful of people who designed and ultimately led the 70-participant meeting sensed both peril and opportunity – peril because the relationship had not been maturing as expected, and opportunity because the conversation offered a great venue for reaching senior leaders and moving the process forward.

The planning team, comprised of five internal stakeholders from both companies, realized that in order to transcend the barriers that existed between the two organizations, participants had to come together in conversation. Working with Laurie Durnell from the Grove Consultants International, Lenny Lind from Covision, and me from Conbrio, team members chose a bold design that combined graphic facilitation, computer-assisted fast-feedback technology, World Café principles, and Storymapping™ in ways that created a whole much larger than the parts. This combination of tools, the planning team reasoned, would prompt breakthrough conversation and ultimately a commitment to invest time and resources in resolving key issues.

That’s exactly what happened. “It turned out the synergy of the design elements coming together created a unique situation beyond what we or anybody else expected,” said Lenny. “The amount of work accomplished was enormous.” By the end of the conference, participants mapped out specific action plans in five categories. What follows is what Laurie, Lenny, and I saw and heard, the discoveries we made, and the questions we’re still living with.

At a Snail’s Pace

First, some background. For the two companies (they want to remain anonymous), the walk toward convergence began five years ago, when both sought to solve the problem of providing superior service to the world’s largest companies in the U.S., Europe, and Asia. The companies are in an industry where it’s difficult to grow organically. At the same time, neither wanted an outright merger with the other. Their solution was to strike a partnership. Two years ago, they decided to strengthen that partnership and to both market and serve clients as if they were one organization.

Since making the agreement, implementation moved slowly so slowly that frustration boiled up in both companies. Negotiations on branding and a short list of other items necessary for a successful joint venture slowed to a snail’s pace. There was talk, some of which leaked to outsiders in Europe, that one company would spurn the other for a better match. It became clear that the December meeting would be vital for moving the partnership forward.

I began my work with the two companies in the spring of 2005, in time to participate in the May semi-annual meeting. The meetings were started three years earlier to bring together large account managers and leaders from both companies across the globe to build relationships so they could better team to seek new and serve existing customers. More than a hundred people participated in each of these events.

The May conference was a dud. A meet-and-greet affair, it was long on long-winded speeches and short on participation by attendees. A barely understandable economist held forth on the state of the world. An interminable panel discussion tried and failed to shed light on customer needs. A tour of locations around the city offered little insight into markets. One guest sitting next to me whispered, “This is a lot to go through for a free drink.” A U.S. participant was so disgusted that he bailed 36 hours after arriving and flew home.

A Fresh Start

The client planning team vowed then and there that the December meeting would be more focused and engaging. In July, when the five members gathered in San Francisco with the consulting team, they began to make good on that vow. They decided on a real give-and-take meeting, where podium time for talking heads would be at a minimum, computers would capture and share participants’ thinking, and graphics would play an important part in showing the whole picture. The team would hand-pick participants, keeping them to senior leadership and those who could actually make things happen – fewer than 100 were to be invited.

The meeting design drew on our consulting team’s collective experiences. Laurie and the Grove have a decades-long history of working with groups using visuals and visual language, including graphic facilitation. She says, “Visuals, graphics help draw people out, communicate ideas, and organize information.” Since 1992, Lenny has used computers in large group meetings to speed feedback among participants. The technology he has developed, called Council, allows people to enter ideas or view-points into computers and then instantly displays them to everyone in the room. And having used the World Café process several times, I knew the seven café principles – clarify the context, create a hospitable environment, explore questions that matter, encourage everyone’s contribution, connect diverse perspectives, listen together for insights and deeper questions and harvest and share collective discoveries would work well in this context.

All three of us agreed that any one methodology, one process, one tool graphics alone, for example wouldn’t be quite enough because, in Lenny’s words, “It would leave this other thing, like need for information or outlet for planning, that wouldn’t be addressed.” Together, however, Lenny’s technology and Laurie’s graphics combined with our collective sensitivity to group dynamics and our ability to blend, orchestrate, and facilitate elements would allow us to cover all the key areas of presentation of issues, discussion, and action planning.

Once we had established the tools we thought would be effective, the next step was to ask, What exactly will the people at the meeting talk about? What issues needed to surface? Where was the line they could not cross? What could this December conversation accomplish? In our July meeting, Laurie helped the client planning team untangle these questions. She drew simple star people with thought bubbles coming from their heads, one for each stakeholder, seven in all, with outcomes in each of the bubbles. Leaders, for example, needed to better understand the business case for the two companies moving closer together, while company reps in Europe and Asia needed to learn what American clients expect.

Now that they could see the outcomes, the planning team was able to go forward to rough out the hour-by-hour first draft of a three day agenda. They decided to use a custom-drawn “infographic” to visually portray the results of a client survey they would present to spur the first day’s discussion. And they agreed that since all the outcomes couldn’t be fully realized in one meeting, they would focus the conversation on making the case for change. Subsequent meetings would delve more deeply into how they would implement the agreed-upon changes.

COMPUTERS AND CONVERSATION

Participants sat three to a table. This setup facilitated both the Café discussions and teams’ use of computers to input responses. The infographic, which was positioned along a wall, provided a context for the process.

Drafting a minute-by-minute agenda was the next big task. This process guided the subsequent rounds of discussions with the planning committee. Like a script used by a stage manager to call a Broadway musical, the final agenda – 20 pages long contained directions for times, speakers, room set-ups, props, and other notes. Lenny, Laurie, and I used the agenda to work out how we would blend the details of the technology, the graphics, the World Café, and other elements. It also included a mock competition designed to show off the companies’ differences from its competitors and a panel of account supervisors who would illuminate customer service issues. “The planning was 40 to 50 percent of the intervention,” Lenny recalled. “The strong upfront process allowed us to design the session step-by-step so that it achieved all of the planning team’s goals while deeply engaging participants in creating a new future for the organizations.”

After the usual opening segments, results of a customer survey would be the main event of the first day. We would use the infographic to focus the presentation and then shift to World Café conversations. Lenny’s computers would capture reactions, quickly feeding them back so that participants, and especially key leaders, could see the collective thinking that emerged in the room. This back-and-forth between presentation and feedback was the structure that allowed creative problem-solving to emerge over the course of the meeting. The next day, we would start more café dialogues then move to a panel discussion, the mock competition, and more café conversations focused on action. Action planning in breakout groups would end the second day. The same groups would continue their action planning the morning of the third day. The conversation would wrap up at noon.

The planning team took those first minute-by-minute drafts and, in a series of meetings and conference calls with us during the fall, made them their own. They wrote, rewrote, and wrote again the café questions. They changed and changed again the infographic. They flipped and reflipped agenda activities. They ordered more implementation planning. They let more presentation time creep in, then, reluctantly, pulled it out on our recommendation. They settled on the final draft just days before the event.

The Main Event

The conversation opened just past noon in a ballroom at the Four Seasons Hotel in San Francisco. Participants entered to find the room set up with small, three-foot-diameter round tables, three chairs per table. Lenny put a computer at each table on top of a large sheet of paper that participants could use to take notes. We placed three dots one red, one blue, one green on the paper. Participants had one of the three colored dots on their name tags. In changing from table to table during café rounds, they could sit only at places where the dots on the table matched the dots on their name tags. The dots were meant to mix participants from different parts of the globe and different ranks in the organization (see “Computers and Conversation”).

Lenny, Laurie, and I went round and round on table size. The ideal number of people per computer is three. Lenny had been used to seating six people per table with two computers, partly because of wiring issues. Café discussions are best when four people sit at a small table because all can easily participate in the conversation. My fear was that larger tables would stifle discussion. I sought out Juanita Brown, co-creator of the World Café, who settled the issue when she advised us that three people per table would work much better than six.

As part of the first hour of the conversation, Lenny introduced his Council technology with three icebreaker questions. This process familiarized participants with the technology. Everyone could see all the answers on their screens, displayed without attribution. The anonymity continued throughout and allowed for an open and honest exchange.

Laurie explained the 14-foot-long infographic, how it was put together to tell the story of worldwide trends, what customer needs resulted from those trends as reported in the customer survey, the companies’ combined response to those needs, and the gaps between needs and responses. Then leaders began their presentation, using the infographic to which the group had just been oriented.

The first café round came after the first half of the presentation. It was a two-question round with participants entering their responses into their computers by table as they neared the 15-minute limit for conversation. Another round came after the second part of the presentation, this time with three questions. The final question was “What’s important for you as a group to explore further and understand?” At the end of each round, four participants, whom we dubbed the “Theme Team,” sorted through the answers, distilling them into themes, key questions, and comments.

The next morning started with the “Deep Dive Café.” Participants tackled three more questions, designed to support disclosure of the deeper issues, rotating to new seats after each question. The questions were straight-forward:, “What’s taking shape? What are the unsaid issues around these themes? What’s the most important insight from our discussions so far?” Table groups entered answers to the last question into their computers.

A Pivotal Moment

It was during the Deep Dive Café that one of the most senior leaders became anxious and nearly cancelled the rest of the event because the discussion strayed into areas of overall strategy. The client planning team pushed back, pointing out the concerns voiced in conversations at the tables and through the computer were overwhelmingly similar and reflected what people were really thinking. The leader allowed the meeting to continue. “The planning team’s work ahead of time combined with the theme team’s work during the conversations gave the team’s members complete confidence in addressing this leadership challenge,” said Laurie. “They understood how things flowed, and when things got rocky over the issues in the room, it allowed them to remain calm, convince the leader to continue, and then successfully complete the agenda.”

Now past the pivotal point, the attention turned to learning more about the gaps between customer needs and service capability. Four representatives who led global customer service teams told of their triumphs and frustrations. Participants both posed questions and made comments through the computer. Following lunch, participants broke into three groups to simulate a sales pitch. One of the three played the role of competitor and soundly beat the other two because, as one integrated global company, it had more and better services to offer the prospective client and in a way that better met the client’s needs. Through the computer, participants identified gaps in each team’s service offerings.

Each of the processes works well alone, but in combination, the strengths were maximized and the weaknesses minimized.

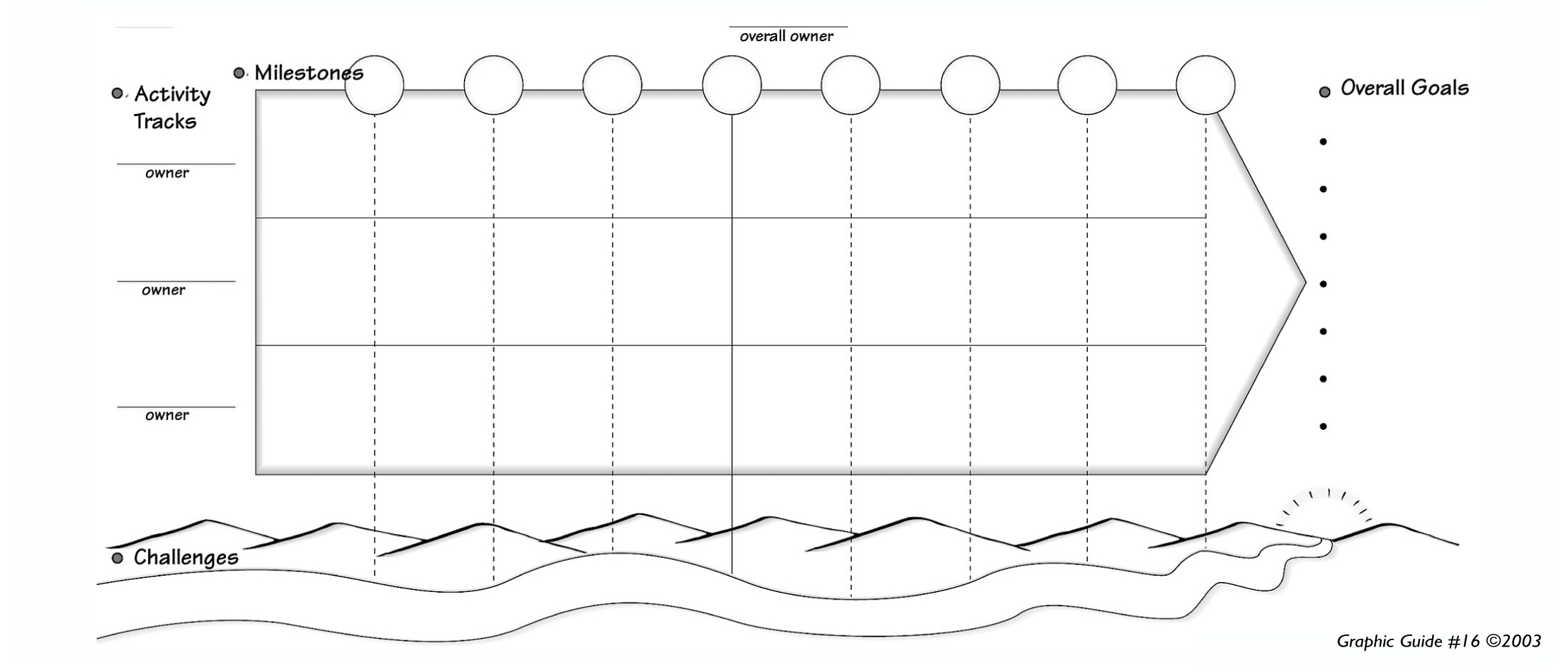

Participants went next into the Action Café. Again rotating between questions and entering answers into the computer, participants chose the three most critical gaps to work on for the rest of the conference. And they suggested specific areas that might be improved branding, for example, and global project tracking. Drawing from the responses, participants broke into nine different groups to plan how to close the gaps over the next six to 18 months. They worked on the specifics through the end of the day and throughout the next morning, focused by wall sized versions of a planning tool developed by the Grove called the “Graphic Roadmap” (see “Graphic Roadmap Template”). Each breakout group presented their plans to the rest of the participants before the final café rounds closing the conference.

GRAPHIC ROADMAP TEMPLATE

Designed by the Grove, the Graphic Roadmap is a large-format worksheet of actions and target dates for deliverables on a project or an organization change process. A signature element is the identification of “milestones.” These are the key dates for events and deliverables that everyone will work to achieve.

“Softening Hard Soil”

In analyzing the conference results in a conversation with Laurie, Lenny, and I, Juanita Brown saw that the combination of the visuals, the World Café process, and the Council technology “heightened the possibility of collective intelligence. One of the big things we find over and over in café work,” she said, “is this very intentional cross-pollination of mix, mix, mix. It’s softening hard soil, so the soil can be receptive to new ideas.”

The computers served as the “common tablecloth on the café table of conversation,” Brown said, that everyone in the room could refer to. It made the collective knowledge visible and led to an accepted conclusion in the whole room at a much earlier stage than is the case in many meetings. In a normal café dialogue where there aren’t any computers, she said, people sense their common conclusions, but they don’t have the level of detail to support them that the computer feedback supplies. The anonymity of the answers also helped with the positive meeting result, Brown said. “You don’t know where the ideas are coming from, so people can more easily accept innovative thinking as it is revealed in the spaces among participants. The space between the ‘me’ and the ‘we’ becomes more fluid and the ‘magic in the middle’ has the opportunity to emerge more easily.”

Conference attendees were just as enthusiastic. As they moved to close the conference, participants answered one last question through the computer: How did this conference compare to the last? “Phew! We had to work this time. The format, structure, people were spot on.” Said another, “It was great!”

So what did we learn? What questions remain unanswered? We learned the whole was far greater than the sum of its parts. Each of the processes works well alone, but in combination, the strengths were maximized and the weaknesses minimized. Also, we confirmed again risk-taking combined with collaborative planning are important. So is quickly creating a sense of “we” in a room divided into many camps.

Will the agreements made, the visions offered, hold up? We don’t know. The big question is how a process can further deepen commitment to action, and how, really, conversation in big groups can ultimately lead to significant action.

Bill Bancroft (bbancroft@conbrioamericas.com) is founder and principal of Dallas-based Conbrio. He designs and leads conversations for companies, organizations, and communities to help leaders with strategy, team building, communications, culture, and other organization issues.