Imagine that you work for a company that has created a powerful and compelling shared vision. Furthermore, you and your colleagues have established a set of values that supports the empowerment of all employees. Your management team has also worked on surfacing deep-rooted mental models around control and hierarchy, and have launched a restructuring effort aimed at flattening management levels and pushing authority as far down the organization as possible. All in all, you’ve achieved some impressive results. But will these efforts lead to an empowered, high-performing organization?

Why Empowerment Fails

While many managers have embraced the idea of “flat” organizations composed of empowered individuals, the existence of such organizations is far from a reality. If empowerment is truly valued, why have so many companies failed to make it happen?

The answer to this question may lie in the lack of organizational structures and norms that support empowered decision-making. Fundamentally, empowerment is about the distribution of power. In organizations, this is most tangibly represented by decision-making authority — who has the power to make what kinds of decisions. But empowerment does not magically turn everyone into great decision-makers, nor does it suddenly equalize differences in skills and experience. Unless the organization’s decision-making processes are designed to ensure the quality of the decisions, empowerment efforts are destined to fail. Even worse, that failure can lead to bitterness and disillusionment.

So, how can we distribute decision-making authority in a way that truly empowers people, yet still protects the organization from undue risks that can come from uninformed decisions? This is the central challenge of walking the empowerment tightrope: balancing management authority and employee influence.

Organizational Straitjacket

When initiatives such as empowerment or employee involvement are announced, there is a tendency to promote a new way of operating by condemning the old. In the case of empowerment programs, this often translates into a belief that decisions made individually are bad (the old model) and that decision by consensus is good (the new model). But as Robert Crosby, author of Walking the Empowerment Tightrope, explains, management exclusively by consensus can be a disaster. “When overused, consensus is time consuming and is often controlled by the most rigid or resistant members.” In effect, we end up trading one form of tyranny for another.

The assumption that empowerment equals consensus decision-making can create organizational straitjackets that lead to poor-quality decisions — and, ironically, can also leave employees feeling disempowered. One manufacturing operation discovered this counterintuitive behavior when it tried to create a flatter management structure through empowerment. The intention was to increase autonomy while improving both the speed and quality of decisions. But after several months, people felt less empowered to make decisions. Worse, many decisions took longer to make, which meant that more were made “under the gun” — and were therefore based on time pressure rather than on sound thinking and adequate data.

If we look at this phenomenon from a systems perspective, we can draw out the counterintuitive dynamics that are at play (see “Consensus Decision-Making Straitjacket”). In the “new” environment of empowerment and teamwork, the “old” view of making decisions single-handedly is viewed as bad. Therefore, Manager A is reluctant to make decisions on his own, even though his position may require it. Instead, he consults with various people and asks for their input. This reinforces the consulted individuals’ belief that it is a consensus decision, so they begin to research different options and feel that they “own” the decision.

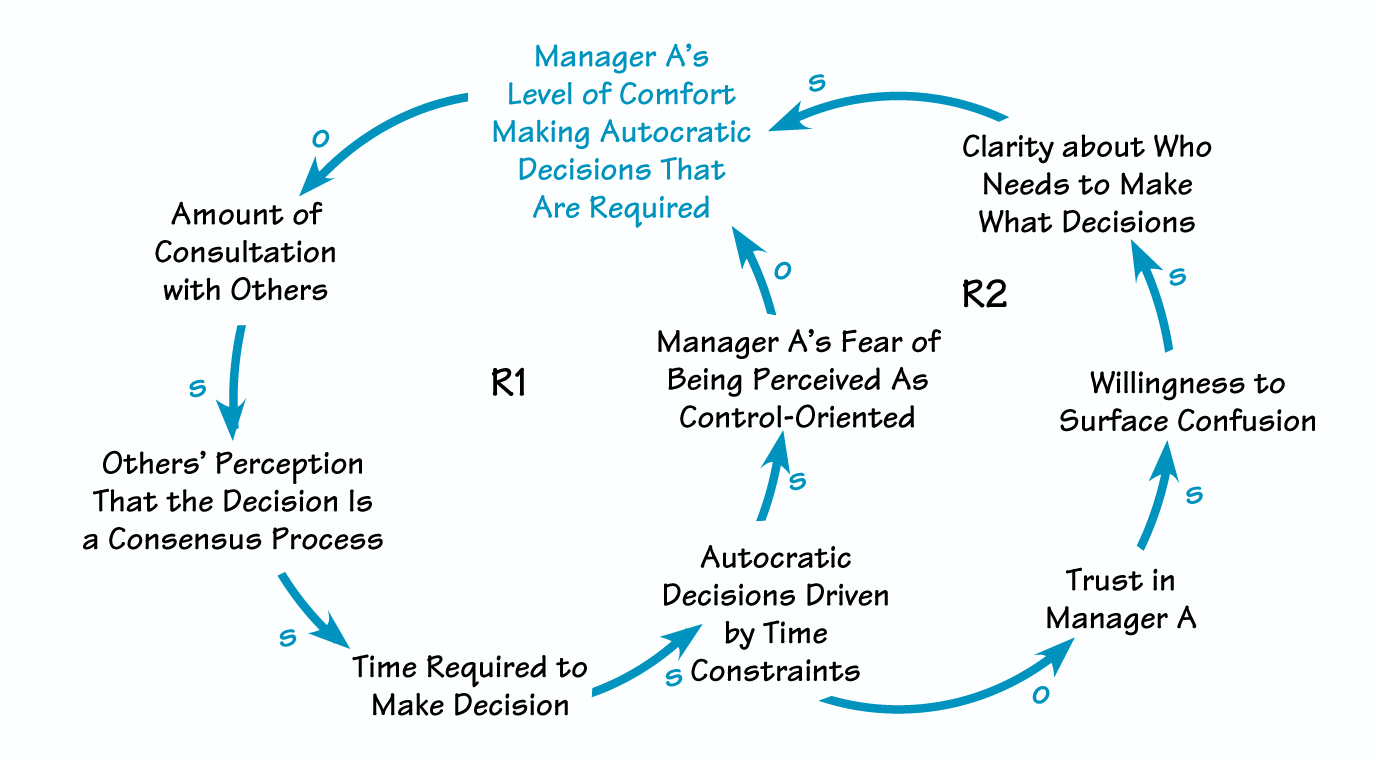

CONSENSUS DECISION-MAKING STRAITJACKET

Lack of clear structure around empowered decision-making can result in a consensus decision-making “straitjacket”—a spiral of ever-increasing resentment on the part of employees and escalating levels of stress and paralysis on the part of the manager.

Although Manager A knows he needs to decide quickly, he feels uncomfortable taking that step alone because others are now actively engaged in the process. The time arrives, however, when action must be taken. Under pressure, Manager A makes the decision even though he has not closed the loop with everyone. Afterwards, he thanks everyone for their involvement and explains the reasons for his action. Although his decision was ultimately a good one, Manager A is left with a nagging fear of being perceived as control-oriented, which further reduces his comfort level with making such decisions and leads to more ambiguous decision-making in the future (R1).

And what about the people with whom he conferred? They are now cynical about Manager A’s commitment to empowerment and the value he places on their involvement. Thus, their willingness to surface their confusion about the decision-making process decreases, and the clarity about who needs to make what decisions never gets established. This, in turn, further reduces Manager A’s comfort level (R2). Both of these loops can lead to a spiral of ever-increasing resentment and mistrust on the part of employees and escalating levels of stress and paralysis on the part of the manager.

A New Decision-Making Model

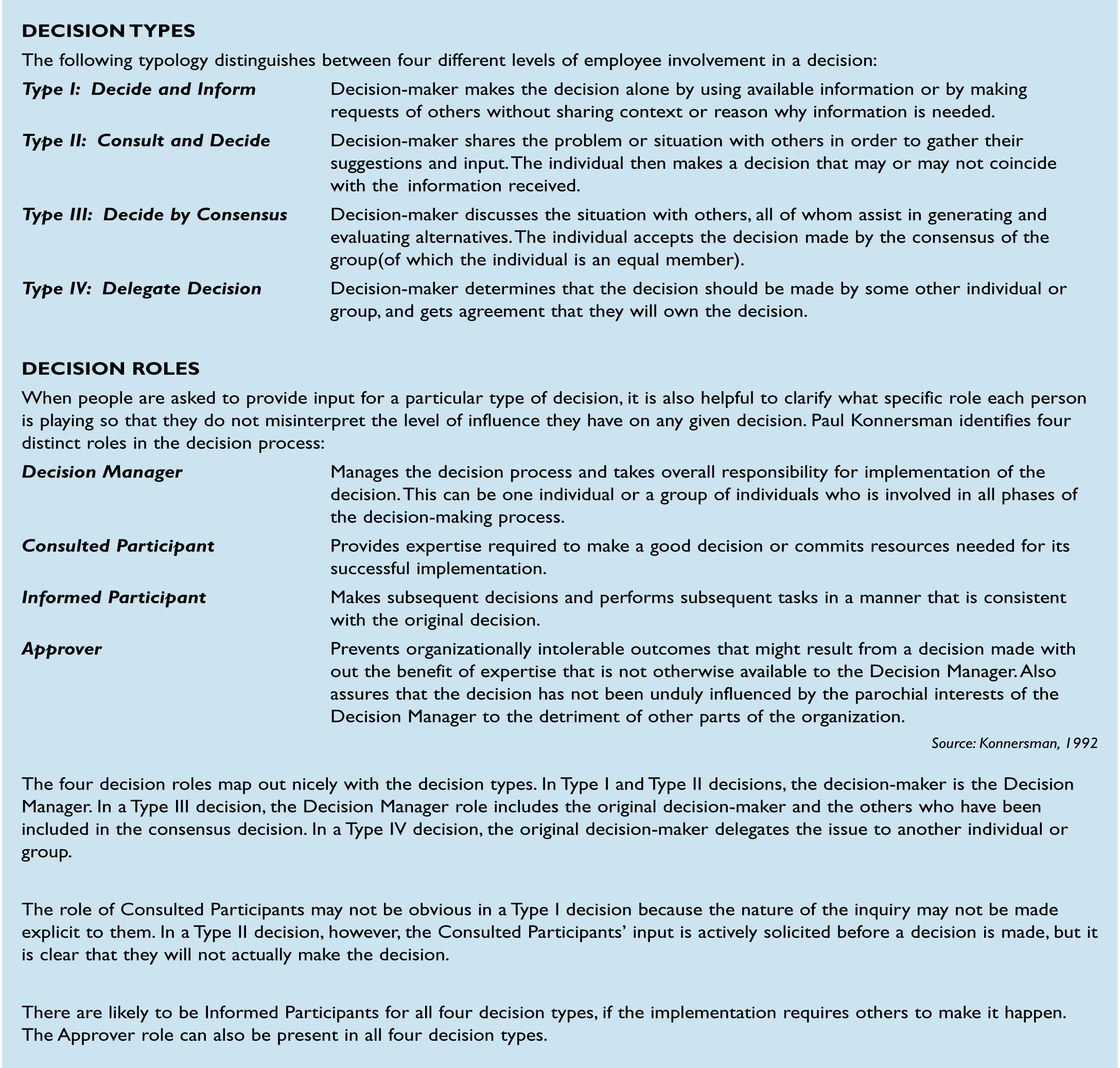

In order to be effective, any decision-making model should provide clarity along at least two dimensions: 1) the type of decision, and 2) the role of each participant. Clarifying the type of decision provides detail on the level of involvement of each person. Deciding on the specific decision role for each person describes the nature and extent of his or her involvement (see “Decision Types and Decision Roles” on page 3).

Identifying the type of decision up front can be an illuminating exercise:

- Is this a decision that you need to make alone, perhaps due to the sensitive nature of the issue? (Type I)

- Can you make the decision with the benefit of some data-gathering conversations with certain individuals? (Type II)

- Is this a decision that requires a consensus among critical stakeholders in order to ensure smooth implementation? (Type III)

- Or, is the decision better left to those who are much closer to the issue at hand? (Type IV)

Determining what type of decision one is facing also begins to surface issues around a second aspect of the decision-making model: who should be making the decision. In effect, by clarifying the decision type, you are also identifying one of the critical decision roles—namely, that of the decision manager.

Decision Manager and Decision Roles

The decision manager, as described by Paul Konnersman in his article “Decision Role Clarification,” is the person responsible for managing the overall decision process and implementation. But identifying the decision manager still leaves room for ambiguity about what type of participation others will have in the decision. Konnersman therefore defines two other roles: the consulted participant and the informed participant. A consulted participant, according to Konnersman, is contacted during the deliberating stage for the purpose of data-gathering, whereas the informed participant is brought in primarily to help with the implementation of a decision that has already been made.

The fourth role in Konnersman’s typology, the approver, can be the trickiest role to fully understand and manage. Although this role is intended to help prevent the organization from making intolerable mistakes, if it is not used properly it can create a feeling of powerlessness and cynicism about empowerment.

DECISION TYPES AND DECISION ROLES

The “Lurking” Approver Role

The approver role is tricky because it can look a lot like the old authoritarian power monger — someone who “empowers” others to make decisions as long as it meets his or her “approval.” And yet, this role is needed when the decision manager is genuinely not in a position — either by breadth of experience or scope of responsibility — to make a decision that is organizationally robust. Although the goal of an empowered organization is to make all decisions as locally as possible, that desire needs to be balanced with the reality of the actual ability to make those decisions.

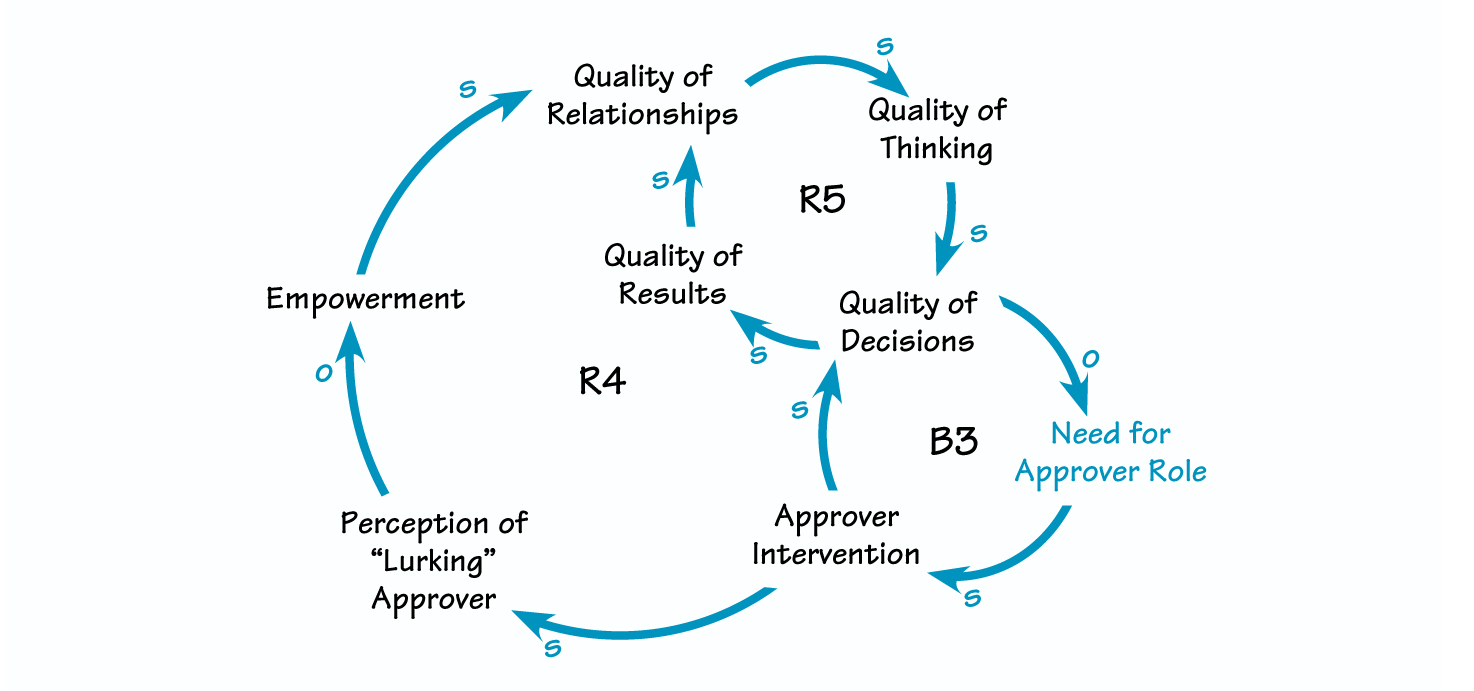

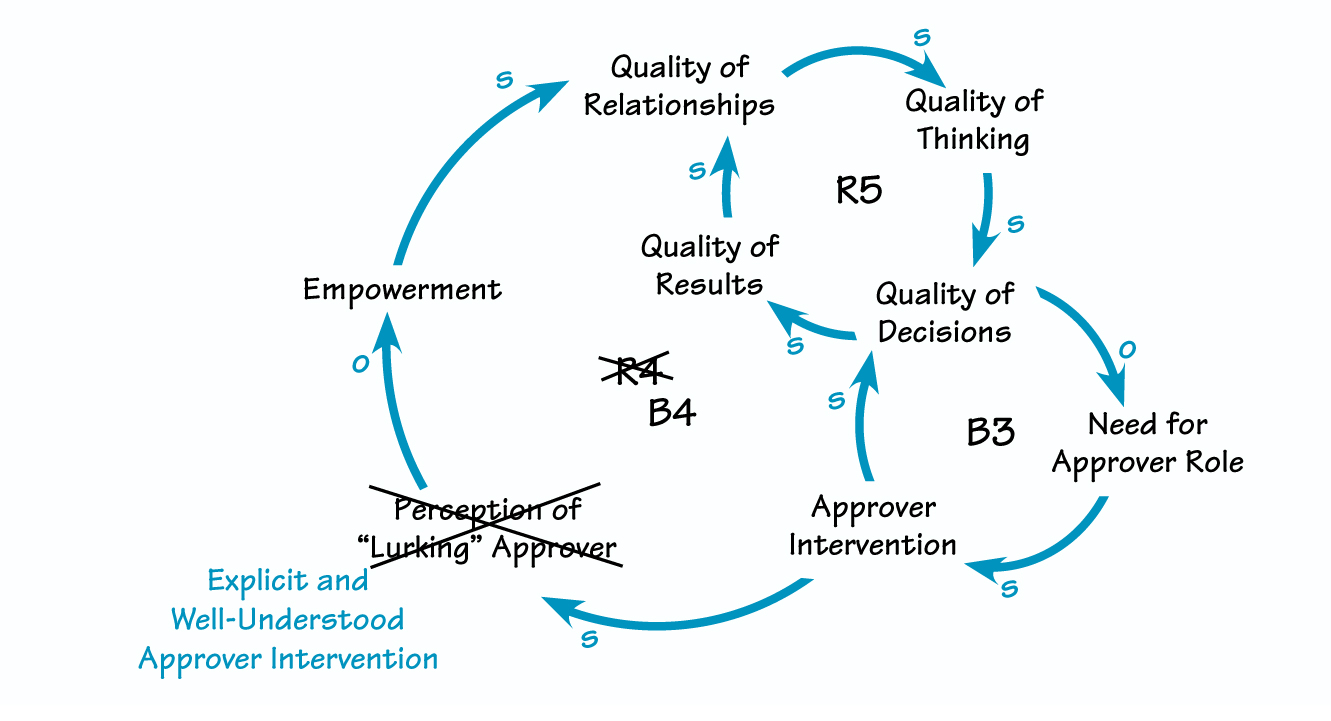

If viewed from this perspective, the approver role can be the means to judiciously manage the transition into empowered decision-making by acting as a safety net for the decision manager as well as for the organization. But if this role is abused, a virtuous circle of ever-increasing organizational effectiveness can be kicked into a downward spiral, decreasing empowerment and leading to lower quality decisions (see “ ‘Lurking Approver’ Dynamics”).

In some situations, an approver needs to intervene in order to improve the quality of a decision (B3). But if the role of the approver is not clear from the outset, it can serve to reinforce the belief that the approver was “lurking” all along, waiting to see if the decision matched what he or she wanted. If it matched, he or she can then point out how the group had been empowered to make the decision. If it did not match, then the approver role can be invoked to make the “right” decision. As a result, the group feels that they were not truly empowered to make the decision. In the future, they will be less likely to put the same level of enthusiasm or trust into the decision process — potentially leading to lower quality thinking and lower quality decisions, which may require further intervention from the approver (R4).

The Approver Role: Setting Boundaries

In such situations, it is not the approver role itself that is the problem — it is the seemingly arbitrary use of the role that leads to a sense of powerlessness. Therefore, the leverage in this system is to identify the approver role in advance, and clearly establish the criteria under which a decision is subject to approval. It is particularly important to identify the specific parameters — the time frame, organizational risk, dollar amount, scope of impact, and other criteria — that will determine when an approver must be involved. Such boundaries provide a pre-negotiated context in which the role can be used most effectively.

“LURKING APPROVER” DYNAMICS

Sometimes an approver must intervene to improve the quality of a decision (B3). But if the approver role is not clarified at the outset, the intervention may breed resentment and lack of ownership over future decisions — potentially leading to lower quality decisions and further need for intervention (R4).

For example, a group may specify that all marketing decisions are owned by the marketing director, but that they require approval by the strategy council if such decisions are in direct conflict with the international market expansion strategy. Or a company can specify a parameter, such as $1 million for capital expenditure decisions or a headcount cap for hiring decisions, above which the decision manager must get approval.

If the person who is empowered to make a decision only finds out that the decision is subject to approval after the fact, empowerment will become a hollow idea that creates increasing bitterness. If, on the other hand, the details of an approver role are outlined beforehand (or at least the possibility of the emergence of such a role is discussed ahead of time) then the actual intervention of the approver can be seen as a self-correcting mechanism. People can see that building this mechanism into the system actually enables a fuller level of empowerment, while still ensuring the quality of the decisions (B4 and R5 in “Clarifying the Approver Role” on page 5).

Walking the Tightrope

Creating a truly empowered organization is a lot like walking on a tightrope. If we completely let go of managerial authority and let individuals always make decisions on their own, we are sure to be erring on the side of abdication. If we are too cautious and afraid of letting anything go, we will surely be accused of remaining controlling and authoritarian. The path of empowerment lies somewhere between those two extremes.

The approver role is critical for accomplishing that delicate balance on the empowerment tightrope. As an organization develops along the path of empowerment, however, one would expect that the number of decisions requiring an approver would decrease and the parameters might relax over time.

No one is going to be perfect in this process — it requires a certain amount of understanding and trust. But trust is a function of at least two things: integrity and competence. All too often, we misinterpret a lack of competence to be a lack of integrity, and we lose confidence in the system and/or in the people involved. If we are a little more forgiving of others when they falter, we may be graced with more understanding when we do the same. And if we have worked to establish a well-defined decision-making structure, we will at least have created a method for consciously selecting who makes what decisions and why. With this kind of guidance — along with a little understanding — we may eventually create the kind of empowered organization that we desire.

CLARIFYING THE APPROVER ROLE

If the approver role is built into the system as a self-correcting mechanism, it can enable a fuller level of empowerment in decision-making, while still ensuring the quality of the decisions.

Daniel H. Kim is the co-founder of Pegasus Communications and the MIT Center for Organizational Learning, where he directs the learning lab research project.

Editorial support for this article was provided by Colleen Lannon.