Let’s say that we have reinvested ourselves in meetings as an integral part of our work and taken responsibility for being present and active participants. Unfortunately, we may still fail in our goal to make meetings more meaningful and productive if we neglect to consider that we all measure value from such sessions in different ways. To honor and leverage our diversity, we must make sure that we consider all learning styles and preferences as we work to improve workplace gatherings.

A FAULTY FIX

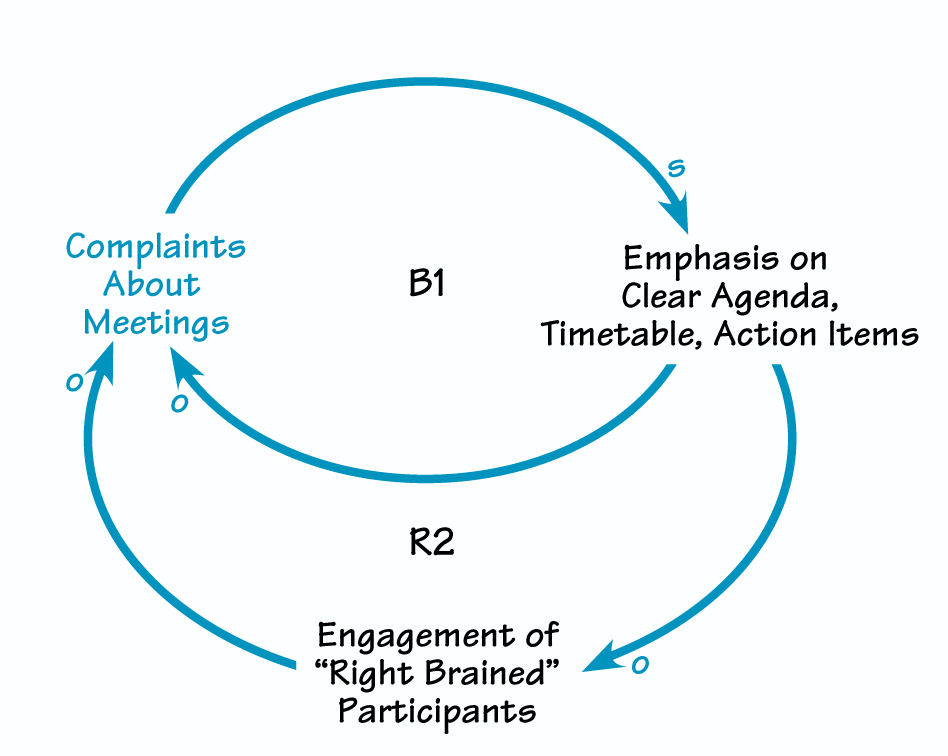

In our efforts to improve the quality of meetings, we often work to clarify agendas, start and end on time, and agree to follow-up actions (B1). But making meetings more programmed may alienate a large group of participants and actually increase dissatisfaction (R2).

Satisfying Some, Not All

Many people in organizations in the West would describe a successful meeting as one in which the agenda was clearly presented and followed, the meeting started and ended on time, and the group agreed to clear follow up actions. Unfortunately, while a clearly planned, efficiently led meeting is often preferable to a meandering brain dump, organization and efficiency alone may not eliminate complaints about meetings. In fact, making meetings more programmed may alienate a large group of participants (see “A Faulty Fix”) — and make meeting even less useful than before.

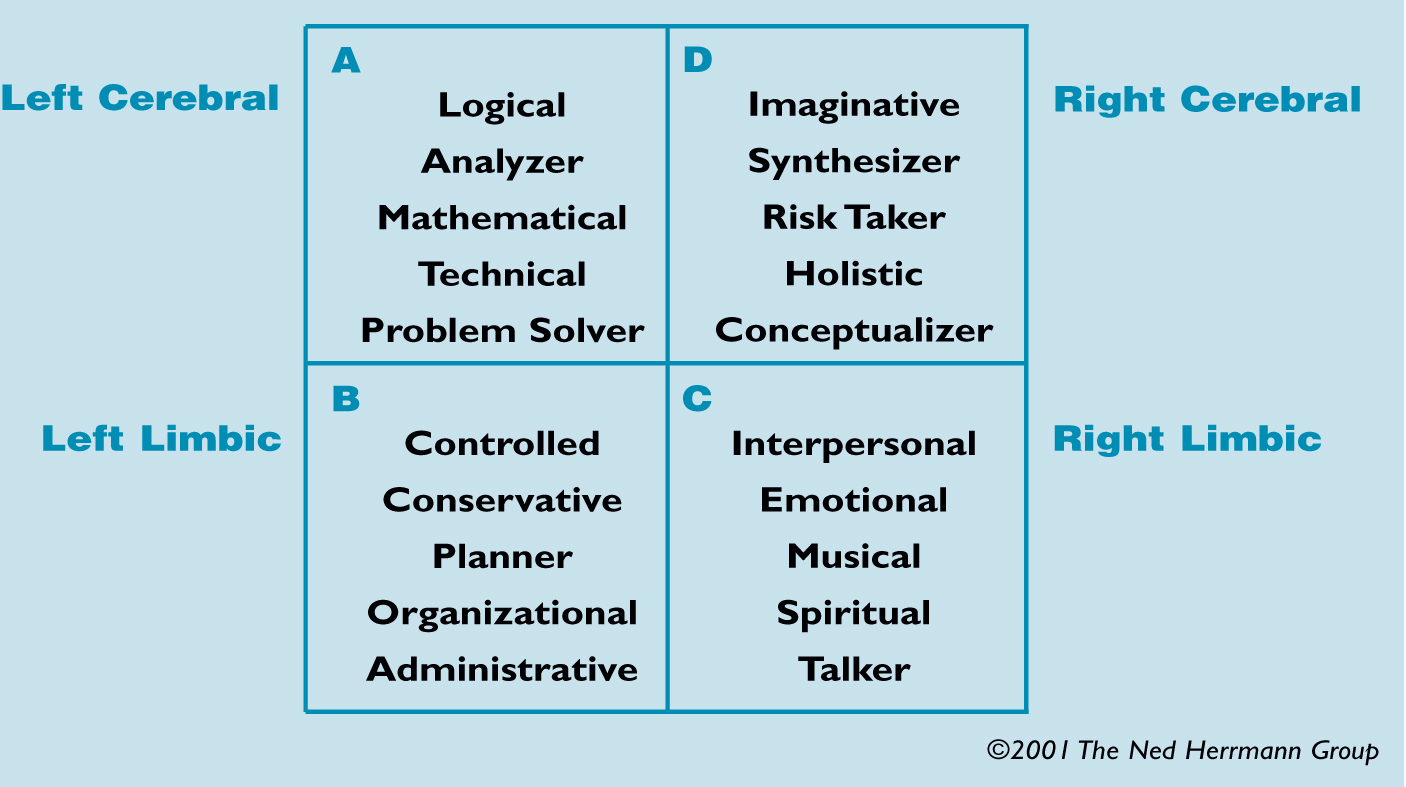

Our awareness of differences in expectations and perceptions of meetings grew as we began to utilize the Herrmann Brain Dominance Instrument (HBDI). Ned Herrmann, an electrical engineer by training, led the leadership development process for General Electric for many years. When the early research on left and right-brain differences emerged, Ned created an assessment tool that measured not just left and right-brain function but also neo-cortex (upper brain) and limbic (mid-brain) preferences. The resulting instrument is one of the most carefully validated measurements of individual preferences in how we process and make sense of what’s going on around us. As such, it gives us a sense of how people with different HBDI profiles participate in and gain value from meetings—or, alternatively, feel alienated by a process that conflicts with their needs and interests (see “Herrmann Brain Dominance Model” on p. 9).

Meetings that reflect each of the four quadrants of the brain would have very different characteristics.

“A” quadrant (left-brained) meetings would:

- Be goal-focused.

- Be brief and to the point.

- Include objectives and an agenda prepared in advance with times, topics, and who is responsible for each item.

- Respect the timetable.

- Focus on the bottom line: Time is money.

- Succinctly articulate outcomes.

- Include appropriate data and financials.

- Allow time for relevant analysis and debate.

“B” quadrant (left-brained) meetings would:

- Respect protocol and include attendees based on rank and responsibility.

- Include a detailed agenda sent well ahead of time.

- Have clearly assigned roles (facilitator, timekeeper, scribe).

- Stick to the agenda. Start and end on time.

- Include a minimum of chitchat.

- Not allow side conversations.

- End with clear action items stating who, when, how, where.

- Include minutes sent to all participants after the event.

- Take place regularly with agreed upon formats. For example, weekly staff meeting, monthly division meeting, quarterly client review.

“C” quadrant (right-brained) meetings would:

- Include time for sharing and building trust.

- Allow for informal, spontaneous, off-line interaction.

- Include activities and/or food to build community.

- Have a check-in process at the beginning to help the group connect.

- Build ownership and strong team interaction by respecting all ideas.

- Include a debrief.

- Invite a cross-section of participants from throughout the organization.

- Take place in a comfortable environment.

- Include facilitation, facilitation, and more facilitation!

“D” quadrant (right-brained) meetings would:

- Be spontaneous about when, how, and whether to meet.

- Constantly stretch the organization’s vision.

- Focus on future possibilities rather than tactics.

- Challenge participants’ assumptions and encourage them to think “out of the box.”

- Take place in unusual places, at different times.

- Include a loose agenda and timetable.

- Encourage doodling and fun.

- Allow for brainstorming and free flow of ideas.

- Include “toys” to stimulate participants’ thinking and help them let go of stress.

- Provide big-picture context.

You may quickly notice that the “A” and “B” quadrants reflect traditional business measures of what constitutes a high-value meeting. Yet these are the antithesis of what the “C” and “D” quadrants promote. Sensitivity to people and relationship issues as well as intuition stem from the “C” quadrant. Visionary, entrepreneurial, creative leaps come from the “D” quadrant. If we ignore the preferences of people who operate from these two quadrants, we will manage and implement projects efficiently but never notice when our products and services have become obsolete or when our customers and employees feel ignored, taken for granted, unheard, or unappreciated.

HERRMANN BRAIN DOMINANCE MODEL

The Herrmann Brain Dominance Model contains four distinct thinking styles, incorporating the left and right hemispheres as well as the upper and lower parts of the brain. We each develop a particular way in which we see the world, process information, and make decisions that reflects the characteristics of one or more quadrants of the brain.

People in more than half the cultures of the world view typical American business “efficiencies” as an insult to their intelligence and a major barrier to building successful relationships. According to Fons Trompenaars and Charles Hampden-Turner, co-authors of Riding the Waves of Culture(McGraw-Hill, 1998), the highly structured meetings of most Western countries would impede success in Latin America and much of Africa and Asia. This echoes the foundational research of Dr. Edward T. Hall and Mildred Reed Hall, who state in Hidden Differences, Doing Business with the Japanese(Anchor, 1990), “Adherence to a rigid agenda and the achievement of meaningful consensus represent opposite goals and do not mix.”

Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner explain that cultures are either specific (relationships prescribed by a contract) or diffuse (whole person involved in business relationships). In diffuse cultures, such as those found in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, people constantly share a great deal of background information. High-trust relationships stem from personal familiarity, so everyone keeps up with the lives of those around them. By contrast, in specific cultures such as North America and Europe, people compart mentalize their personal relationships, work, and many aspects of day-to-day life. They often believe that, to be efficient, they must limit conversations to the immediate topic and not “waste time” on chit-chat.

Nevertheless, some Americans are diffuse, quadrant “C” and “D” people. They understand the big picture and go to meetings with an open mind, expecting to learn from others. For such people, too much structure blocks the flow of communication and trust. They believe in their ability to listen intuitively and achieve consensus by involving each member of the group. These participants do not measure a good meeting by how quickly it adjourns, but rather by how much is shared, resolved, and agreed upon, even though the meeting may have gone well past the time allotted to it. The solution is to dig deeper to find out the underlying cause of discontent. We believe meetings can be substantially improved when:

- all four quadrants are considered in meeting design

- specific and diffuse expectations are addressed,

- a brief evaluation is held at the close of each meeting, and

- the tension between differing perspectives is “held” rather than, “resolved.”

If we have only one system for structuring our time, we may please half the population but organize our business teams in such a way that we fail miserably when we attempt to build deep trust and genuine ownership, deal effectively with other cultures, and even communicate with others in our own organizations. The challenge is to recognize and respect differences in expectations for meetings and hold the “opposites” in tension, without abandoning either preference.

From Uniformity to Variety

Moving from a “one-meeting-fits-all” mindset to multiple settings, styles, and procedures can help answer the cries for “No more meetings!” We can gain great dividends with careful thought about the purpose for calling a meeting. Who needs to be present? For how long? Where would be the best place to meet? What procedure should we use?

We gleaned the following ideas from high-performance teams and companies around the globe:

1. The power of silence. To start the meeting at a deeper level, pose questions, then sit in silence for five minutes before responding. Throughout a meeting, anyone can suggest a silence to encourage self-reflection.

2. Virtual, on-line meetings. Have participants “check in” at the beginning by sharing their state-of-mind and “check out” at the end to help bring closure. Set the agenda in advance, yet leave room for new topics.

3. Conference calls. Ask that people identify themselves before speaking. The group creates the agenda in advance and determines when to move to a new topic and when to end the session. Evaluate the experience at the end to celebrate successes, share lessons learned, and continue to improve process/performance.

4. Walking meetings (usually two people). These informal strolls can be especially good for focusing on a challenging problem. They provide privacy and time to reflect and go deeper.

5. Representative meetings. Instead of having many people participate, invite a smaller group of cross-functional representatives to meet.

6. Missing voice. Pull in an empty chair and make a nametag to remind the group to consider the concerns, questions, and needs of a missing team member, client, or other stakeholder.

Moving from a “one-meeting-fits-all” mindset to multiple settings, styles, and procedures can help answer the cries for “No more meetings!”

7. Outside the office. For a change of perspective, meet at a retreat center, hotel, park, coffee shop, or client’s/ vendor’s plant.

8. Meetings on tape. Record a meeting for an attendee who is traveling or ill.

9. Capacity building. Use meetings to grow younger team members by engaging potential leaders in challenging roles to facilitate, present, critique, celebrate, and evaluate.

10. Huddles. Spontaneous meetings that anyone can convene.

11. Deep Dives. More lengthy meetings to question assumptions around a specific project. The title signifies a need to go deep into details, root causes, and work process improvement.

12. Fireside Chats. Gather teams to provide context, congratulate, encourage, challenge, and work to deeply engage commitment through dialogue.

No matter what the setting, agenda, or content, create and be accountable for a set of ground rules, such as:

- This is a safe zone

- No rank in the room

- Everyone participates, no one dominates

- Help us stay on track

- One speaker at a time

- Give freely of your experience

- Agree only if it makes sense to do so

- Listen as an ally

- Be an active listener

- Maintain each other’s self-esteem

- Keep an open mind

- Maintain confidentiality

- No outside work

- Have fun

One of the best skills we have learned to improve meetings for all involved is to challenge ourselves with at least five good questions in advance, such as:

- How can I add value?

- What is the purpose of this meeting?

- Who will attend?

- What else might I accomplish before, during, or after with any of the attendees?

- Can I double my value by representing a partner, client, or peer?

By finding ways to make meetings meaningful for all participants and capitalizing on the strengths of our diverse workforce, we may finally be able to transform our shared “meeting fatigue” and move to new levels of productivity and enjoyment. Think of meetings as time to build collective intelligence, grow community, and engage highest levels of collaboration. You will know you are on the right track when problems are identified much earlier, solutions are more creative, and work becomes more rewarding and even fun. So get out there and experiment!

Ann McGee-Cooper, Ed. D., has been called a visionary and catalyst for the transformation of American business.

Duane Trammell is a Founding Partner at AMCA, Inc. and coauthor of Time Management for Unmanageable People.

Gary Looper is a Partner at AMCA, Inc. and Project Leader of the Servant-Leadership Learning Community.