Ifrequently work with clients who want to improve their company’s performance—they essentially seek to set into motion the “Flywheel” of ever-increasing success that Jim Collins describes in his book, Good to Great (Harper Business, 2001). I explain to managers about the dynamics of change, and that the only way to achieve sustainable company wealth is through long-term intervention. We spend a lot of time searching for ways to balance long-term interventions with the pressure for quick results. We evaluate how long we need to wait for better outcomes after implementing an improvement program; we visualize both the short- and long-term consequences of our actions; we study examples of policy resistance.

But still, more often than not, managers choose to implement quick fixes over more fundamental solutions that promise to pay off over the long run. What are the reasons, then, for the addiction to fast solutions? Here are some of my findings from companies:

1. Top-level management does not understand the dynamics of change and has unrealistic expectations about the process. When we go into companies, people frequently tell us, “We have gone through five improvement programs during the past three years. Don’t talk to us anymore about change.”

2. After our seminars, managers understand the dynamics of change but they don’t think that they can wait so long for company performance to improve. So they choose between what they see as lesser and greater dangers. In their eyes, it is less risky to try a quick fix or to do nothing; it is more risky to invest in a process that will take a long time to show results. They typically respond, “We do not have enough resources (money, time, people) to realize such interventions. We’ll do nothing for as long as possible, and then we’ll see what happens.” If after some time, the company is still in trouble, they search again for a quick fix.

Setting the Flywheel in Motion

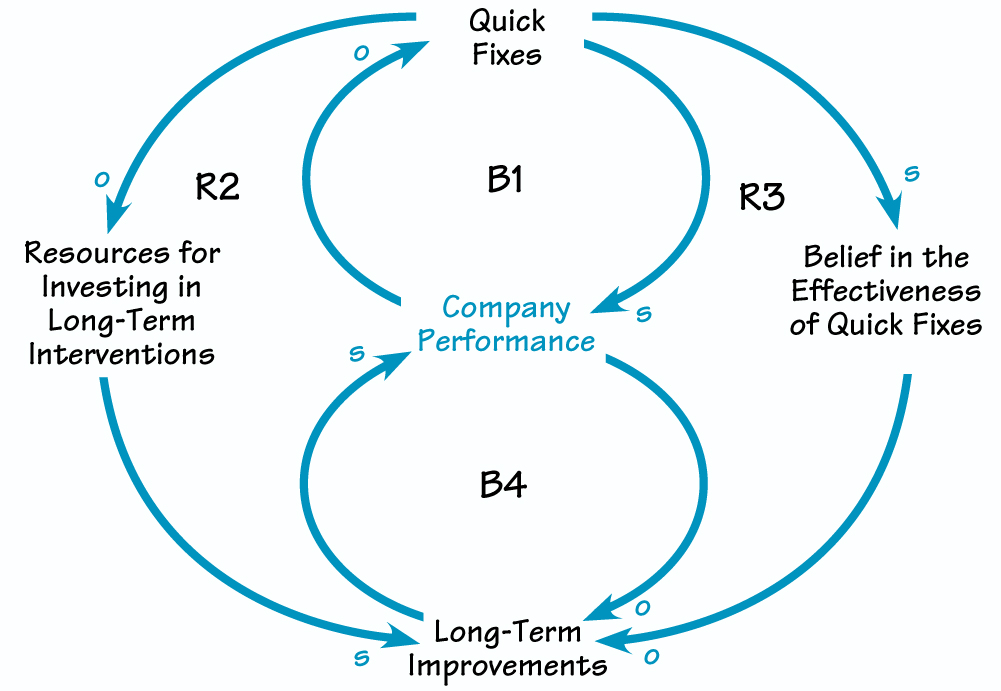

In our workshops, we teach managers that they can have either sustainable success or quick results, but not both. We show how the addiction to quick fixes actually undermines company performance over time (see “Addicted to Quick Fixes”). When managers respond to falling corporate performance by implementing quick fixes, results often improve over the short run (B1, the “Quick Fix” loop). But these actions take away resources from activities that might make the organization more sustainable (R2). At the same time, the apparent success of the quick fixes reinforces people’s belief in the effectiveness of that course of action (R3). All of these actions reduce the number of long-term improvements the company undertakes, eroding performance over the long term (B4, the “Flywheel” loop).

Alternatively, when management has a true understanding of what it takes to achieve corporate sustainability, they are patient and persistent in their search for and realization of long-term investments. As Jim Collins describes it, once the “Flywheel” is set in action, it becomes easier and easier to push!

To begin to substitute the “Flywheel” loop for the “Quick Fix” loop, managers must understand the “Limits to Growth” archetype and the need to invest today in the company’s future. This structure shows that the time to invest in growth and development is when company performance is relatively strong and the organization has ample resources to draw on. But organizations seldom follow this advice. Managers typically follow the imperative from above to lower expenses and maximize profit.

According to my experience, educating managers and other key people in the company is the only way to achieve lasting change—and ultimately, lasting success. I’ve also found that, the bigger the company, the more difficult this educational and change process is. The commitment to follow the “Flywheel” rather than the “Quick Fix” strategy can be easily destroyed by market, financial, and legal pressures. But making this shift is vital for a company that intends to be “great” well into the future.

Addicted to Quick Fixes