As we speak to people around the world about servant-leadership, a practical philosophy that encourages collaboration, trust, foresight, listening, and the ethical use of power and empowerment, most believe that increasing leadership capacity in themselves and their teams is critical to organizational success. What they aren’t sure of is whether the “softer” side of servant-leadership — such as working from a foundation of mutual trust and respect — works when the going gets tough (see “What Is Servant-Leadership”).

Southwest Airlines—which has practiced servant-leadership for 33 years — is one company that has managed to thrive in the face of adversity. In 2001, the company was the only major airline to make a profit. It regularly ranks in the top 10 of the “100 Best Companies to Work for in America.” In a company that is 85 percent unionized, Southwest has been able to develop high loyalty among its people because it instilled the “soft stuff into its organizational processes from its inception.

Preparing for Bad Times

Chairman Herb Kelleher’s motto for both Southwest employees and the airline as a whole is “Manage in good times to prepare for bad times.” To succeed in today’s marketplace, the company cross-trains employees and increases their skill base so that individuals at all levels can take personal responsibility for keeping the company marketable, maintaining high-trust relationships, and identifying effective options for dealing with transitions. In addition, Kelleher and other leaders inspire loyalty by communicating openly and truthfully with their staff, respecting the lifework balance, and fostering continuous learning. Southwest employees know that their voices matter and that they can implement new programs, make decisions, and help customers in times of need. A guiding principle is: If you use your best judgment to do what is right, your leaders will stand behind you.

Southwest Airlines — which has practiced servant-leadership for 33 years — is one company that has managed to thrive in the face of adversity.

Over the years, Southwest management has gone to extreme lengths to avoid layoffs. During the Gulf War, when fuel prices rose so much that the company lost money every time an airplane took off, Kelleher promised to do everything in his power not to address the challenge by laying people off. He, top leaders, and many employees took voluntary pay cuts to keep the company profitable. More recently, following September 11, Southwest was the only airline that did not lay off any workers or reduce its flight schedule.

One reason why the airline doesn’t lay people off has to do with its hiring practice: It looks for attitude before experience, technical expertise, talent, or intelligence. “We can train people to load a plane, take reservations, or serve passengers,” says Kelli Miller, Southwest Airlines marketing manager for Utah. “What we can’t train is good attitude or ‘heart-based’ decision-making.” The company also consistently provides coaching and growth opportunities for people and weeds out non-performers within the first six-month probationary period.

WHAT IS SERVANT-LEADERSHIP

Robert K. Greenleaf, director of management research for AT&T in the mid-1900s and the first to write about servant-leadership in the workplace, said that servant leadership “begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve, to serve first. Then conscious choice brings one to aspire to lead. This is sharply different from the person who is leader first, perhaps because of the need to assuage an unusual power drive or acquire material possessions.”

Servant-leadership contrasts markedly with common Western ideas of the leader as a stand-alone hero. Especially when we face organizational crises, we tend to long for a savior to fix the messes that we have all helped create. Even in impressive corporate turnarounds, we tend to look for the hero who single-handedly “saved the day.” But this myth causes us to lose sight of all those in the background who provided valuable support to the single hero.

Seeing the leader as servant, however, puts the emphasis on very different qualities. Servant-leadership is not about a personal quest for power, prestige, or material rewards. Rather than controlling others, servant-leaders work to build a solid foundation of shared goals by awakening and engaging employee knowledge, building strong interdependence within and beyond the organization’s boundaries, meeting and exceeding the needs of numerous stakeholders, making wise collective decisions, and leveraging the power of paradox.

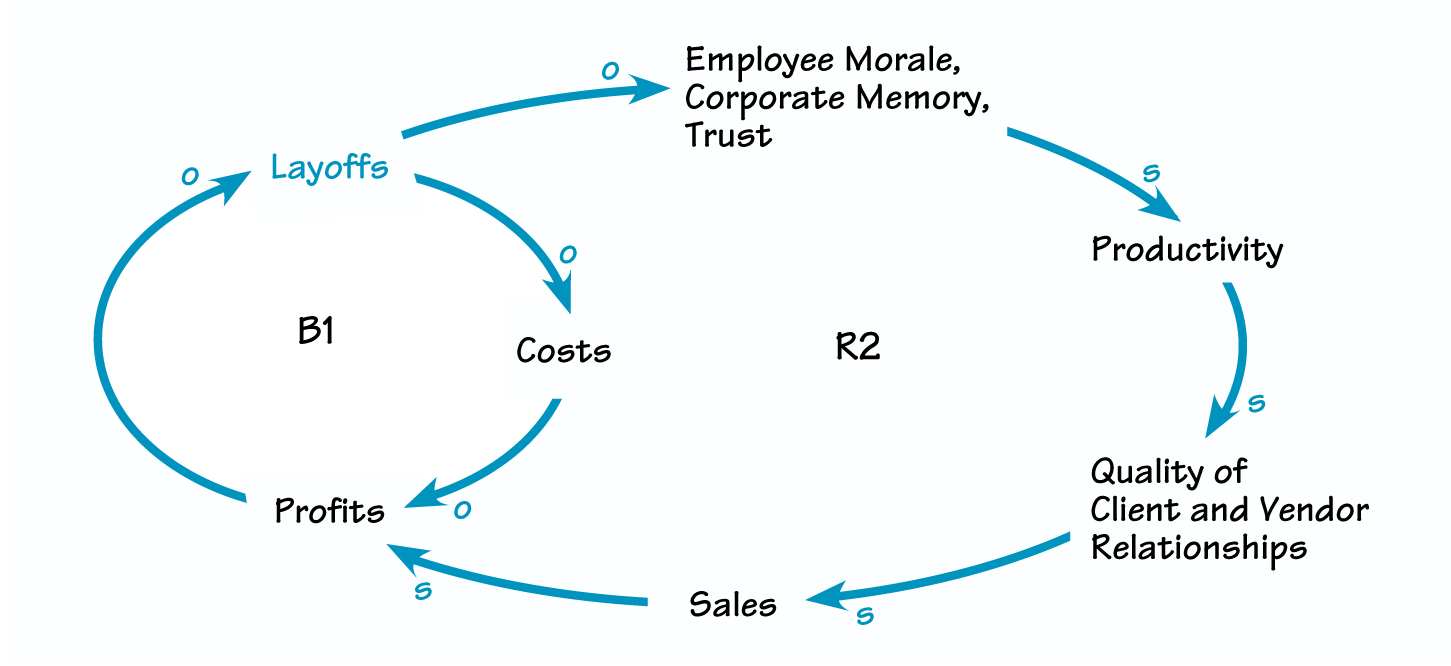

Company managers profoundly understand the negative impact that layoffs can have on employee morale, trust, productivity, corporate memory, and, eventually, bottom-line results. Because they understand that long-term profitability comes from capitalizing on employees’ wisdom and capability, Southwest sees massive layoffs as merely “quick fixes” that often fail in the long run (see “Layoffs That Fail”).

The “Warrior Spirit”

Because of the company’s commitment to its workforce, Southwest employees perform at heroic levels on a daily basis and volunteer to make huge personal sacrifices on behalf of the company in hard times. Says Miller, “This last year has been Southwest’s biggest trial. But preparation for 9-11 didn’t start the day the terrorists struck. It began 30 years ago when the Southwest ‘Warrior Spirit’ was born — the will among leaders and employees alike to fight, to do whatever it takes to make the airline successful.”

Examples of heroic service abound. For instance, in the airline’s early days, when Southwest’s bank repossessed one of its four planes, forcing it to cancel a fourth of its flights, employees got creative. “We figured that if we could turn our planes in 10 to 15 minutes rather than 45, we could still keep the same number of flights even with one less plane,” explains Miller. “This significantly more efficient turn-time set a record in the airline industry. Since then, employees acting as partners to solve difficult business challenges and achieve unheard of levels of productivity has become our tradition and trademark.”

LAYOFFS THAT FAIL

Following September 11, the company’s top three leaders volunteered to work without pay through the end of the year. Immediately, employees sought to help Southwest recoup lost revenue and pledged $1.3 million in payroll deductions. As an article in The Wall Street Journal describes, “Southwest has managed to remain profitable while all others have suffered huge losses. Why? Because of low cost and a productive work force. At no time have those advantages been more striking than right now. And the really interesting thing is that Southwest employees appear to have understood that.”

Donna Conover, executive vice president of customer service, points out that the company has high expectations for each employee. “Just doing your job well does not make you a good employee. The attitude and spirit toward others complete the needs the company has of that employee. As leaders, if we allow lack of teamwork or low productivity, we are being unfair to the rest of the team.” Time and again, Southwest employees have more than held up their end of this new employee-employer contract.

A Shining Example

Through the deep mutual trust and sense of ownership that characterize their cultures, Southwest and other companies that embrace servant-leadership have achieved remarkable results that put them at the head of their industries. These achievements don’t happen by accident or through guesswork — they are the result of leaders who commit to serving their employees and, in turn, providing their customers with the best products and service in the marketplace. This is a formula for success in even the most challenging economic climate.

To return to our opening question, “Does the soft stuff really work when challenges are tough and complex and the future of a company is on the line?” What we have repeatedly learned from clients who have practiced servant-leadership over several decades is that the strength of organizations comes from their people. You can’t micromanage people one day and expect them to think and act like owners the next. It takes a long time to grow business savvy at every level of a company. If you don’t begin early to invest in developing people, building mutual trust and respect, and engaging meaningful collaboration at all levels, you will not be able to leverage your employees’ potential when a major crisis hits. Servant-leadership offers a way for leaders to bring out the best in others by offering the best of themselves.

Ann McGee-Cooper, Ed. D., is coauthor of The Essentials of Servant-Leadership: Principles in Practice (Pegasus Communications, 2001) and founder of a team of futurists focusing on servant-leadership, creative solutions, and the politics of change. She has served on the Culture Committee of Southwest Airlines for the past dozen years.

Gary Looper is a Partner at Ann McGee-Cooper & Associates; Team Leader of the 10-organization Servant-Leadership Learning Community; and coauthor of The Essentials of Servant-Leadership.