Why are attempts to transform organizations usually painful and so often unsuccessful? Why is it that, even when leaders recognize the value of the tools and principles of organizational learning, plans to implement them frequently fall short? Not surprisingly, we have found that the level of personal development of the CEO and his or her senior advisers can have a critical impact on the success of organizational change efforts and, in turn, on a company’s ability to thrive in an ever-more complex business environment.

Some researchers have argued against focusing on the CEO in predicting a company’s destiny. But we have found that a leader’s support for and legitimization of change efforts are crucial in sustaining companywide transformational processes until results persuade an increasing proportion of the workforce to commit more fully to the new order. This is especially true when the efforts involve new practices that aren’t widely understood or used, like the tools and concepts of organizational learning. And, conversely, a single CEO incapable of exercising, recognizing, or supporting transformational power can be enough of a bottleneck to undo prior organizational abilities and accomplishments. Thus, regardless of what else is happening within the organization, a CEO can have a major influence on the likelihood of organizational transformation.

Studying Organizational Development Efforts

For 10 years, we participated in and studied 10 organizational development efforts, spending an average of about four years with each business. The organizations included both forprofit and not-for-profit enterprises that ranged from 10 to 1,019 employees, with an average of 485 staff members. The businesses represented numerous industries, including financial services, automobile, consulting, healthcare, oil, and higher education. Based on several criteria, we found that seven of the 10 organizations prospered: They experienced significant improvements and became industry leaders on a number of key indices. On the other hand, despite our best efforts, three of the 10 organizations did not progress and lost personnel, industry standing, and money.

In examining these cases retrospectively, we noticed that the companies whose CEOs had certain perspectives and values were more likely to achieve favorable outcomes in the organizational transformation process than those that didn’t. We found that the more successful leaders recognized that there are multiple ways of framing reality, and understood that personal and organizational change require mutual, voluntary initiatives, not just top-down, hierarchical guidance. For instance, in one organization, the leader, with her management team and consultant, created a new strategic planning process that enlisted the active and playful involvement of all staff members in designing the organization’s future. In another, the CEO created a series of voluntary learning opportunities for two vice presidents with whom the rest of the senior management team reported having difficulties.

As shown by these examples, this group of CEOs intuitively embodied many of the key elements of the five disciplines. They encouraged shared visioning, team learning, discovery and transformation of mental models, and development of personal mastery. If someone within the organization did not appear to “buy in” to the learning process, the CEOs did not unilaterally fire the person or generate pressure for external conformity “to the program.” Instead, they engaged with the individual to explore the systemic effects of his or her actions on the rest of the organization and presented opportunities for personal and professional growth.

In the organizations that didn’t change, the CEOs actually impeded change efforts, either through benign neglect of existing learning structures or through actions that undermined the transformation process. For instance, one leader eliminated by simple disuse many of the peer learning systems built into the organization when he arrived, gradually turning the operation into a crisis-prone, reactive entity.

Individual and Organizational “Action-Logics”

To aid us in analyzing and comparing the characteristics of the different leaders and organizations, we referred to developmental theory. Developmental theory traces its roots to the philosophies of Plato and then Hegel. It became part of

In the organizations that didn’t change, the CEOs actually impeded change efforts, either through benign neglect of existing learning structures or through actions that undermined the transformation process.

empirical science with Piaget’s studies of children in the early 20th century. Developmental theory is based on a progression of capabilities that an individual or organization may possess. Each stage serves as the foundation for the one that follows; that is, a person or group must master the characteristics of an earlier level before moving to the next one.

During the past quarter century, researchers have increasingly studied and developed measurement systems for evaluating adult development. At the same time, some colleagues and I have articulated a parallel theory of organizational development. The table “Managerial Action-Logics” offers brief impressions of the characteristics of managers at different stages of development; “Organizational ActionLogics” does the same for organizations. We use the term “action-logic” to highlight how, at each developmental stage, the assumptions that people or organizations hold affect their ways of making meaning of themselves and the world, of thinking, of acting, and of interpreting feedback.

How do people and organizations move from one developmental action-logic to the next? The most important point is that there is no way to “make” individuals transform by external force or persuasion alone. Although most children transform from the self-centered Opportunist action-logic to the other-focused Diplomat one as they become teenagers and wish to be liked by peers and rewarded by teachers, a small percentage of managers are measured at the Opportunist level in later adulthood. So, persons and organizations must, in some basic sense, volunteer for transformation.

MANAGERIAL ACTION-LOGICS

Opportunist

Seeks short-term, concrete advantage for self; rejects feedback; externalizes blame; manipulates others.

Diplomat

Seeks acceptance by colleagues; observes protocol; avoids conflict to save own and other’s face.

Expert

Seeks causes and perfect, efficient solutions; accepts feedback only from master of the particular craft.

Achiever

Seeks effective results by teamwork; welcomes goal-related, single-loop feedback.

Strategist

Seeks to construct shared vision, transformational conflict resolution, and timely performance through creative, witty, double-loop, reframing feedback.

Magician/Witch/Clown

Seeks triple-loop, transformational “systems experiencing” that creates positive-sum, mythical events and games by blending opposites (e.g., civil disobedience, feminist politics, social investing).

At the same time, wanting to change isn’t enough to guarantee personal or organizational transformation. The assumptions of one’s current action-logic tend to undercut efforts to operate according to the next, more encompassing action-logic. Consequently, leaders and organizational systems that exercise mutually enhancing power are critical for helping others make the leap to the next action-logic. For instance, in the earlier story about the two vice presidents who were challenged to change their behavior, one undertook a series of learning experiments that increased her coworkers’ level of trust in her. The other resigned after two half-hearted gestures at altering his behavior. Two years later, the second VP called the CEO to thank him for encouraging him to embark on a journey of personal growth. He reported that, after he was fired three months into his next job, he had entered therapy and discovered the degree to which he had previously shunned all well-meant attempts to help him move to the next developmental level.

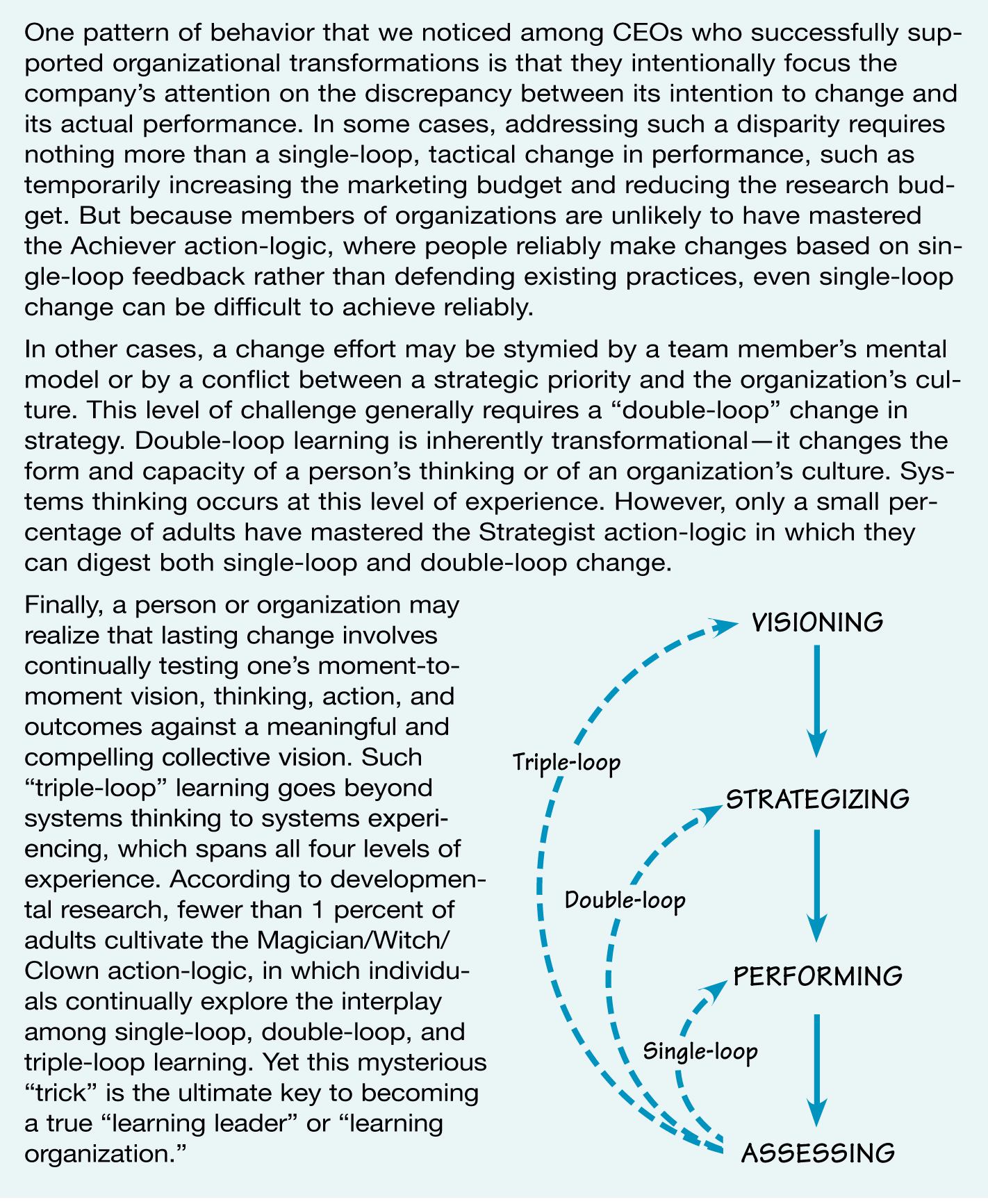

Nearly 60 percent of the adults studied in organizations operate according to the Opportunist, Diplomat, or Expert action-logics, yet it is only at the Achiever level (where about 30 percent of managers fall) that people reliably use single-loop feedback to improve their performance (see “Barriers to Organizational Change” on p. 4). When we consider that only about 10 percent of managers currently measure as exercising the Strategist action-logic, which is the first level at which a leader explicitly initiates double-loop, transformational learning, we understand why “learning leaders” and “learning organizations” are so rare.

Individuals who develop to the Strategist stage or beyond can appreciate the paradoxes of exercising what we call “vulnerable power.” They understand that only by exercising power in such a way as to make ourselves vulnerable to transformation can we hope to encourage voluntary transformation in others rather than mere conformity, compliance, or resistance. For example, one CEO openly presented his weaknesses and shortcomings as a leader to his senior team during a time of organizational crisis. Based on this openness, the team was able to assign responsibilities so as to eliminate potential blind spots, challenge each other to develop new skills, and provide regular feedback on each other’s performance. In this way, Strategists are true learning leaders. In contrast, leaders at earlier stages of development would reject out of hand the actions of the Strategist CEO described above. A Diplomat CEO, for instance, would feel threatened by the prospective loss of face in publicly describing his or her weaknesses. In fact, the one Diplomat CEO in our sample companies was so unwilling to work constructively with any negative feedback that eventually his entire strategic planning team resigned, the consultants resigned, and the organization continued to lose money and reputation. Expert and Achiever CEOs are increasingly more likely to be able to cope with negative feedback than the conflict-avoiding Diplomat. However, unlike Strategist CEOs, who are generally able to gauge what actions to take based on the specific situation, Experts and Achievers are less open to generating creative solutions.

What does it mean for an organization to progress developmentally, and how is this kind of improvement related to organizational learning? As in human development, each transformation in organizational development represents a fundamental change and increase in the organization’s capacity. In transforming through the first three action-logics (Conception, Investments, and Incorporation), an organization grows from a dream into a functioning, producing social system. If it transforms through the second three action-logics (Experiments, Systematic Productivity, and Collaborative Inquiry), the organization gains the capacity to change its strategies and structures intentionally. Just as few persons today evolve beyond the Achiever actionlogic, few organizations today evolve beyond the analogous Systematic Productivity action-logic. But when they do (as in the case of Alcoholics Anonymous and the Jesuit Order), they become capable of helping their members develop to the point of recognizing and correcting incongruities among their visions, strategies, actual behavior, and outcomes; that is, they become true “learning organizations.” In short, each organizational transformation from one action-logic to the next represents major organizational learning.

ORGANIZATIONAL ACTION-LOGICS

Conception

Dreams, visions, informal conversations about creating product or service to meet inadequately addressed need.

Investments

Early spiritual, social, financial investments sought from potential stakeholders and champions.

Incorporation

Recognizable setting; tasks identified, roles delineated, and products/services produced.

Experiments

Alternative administrative, production, financing, and marketing strategies and structures tested.

Systematic Productivity

Hierarchical structures and procedures formalized, with quantitative measurement of outcomes, within competitive ethos.

Collaborative Inquiry

Co-generation of cooperative, inquiring, creative ethos and network; shared vision; openness about differences and incongruities; performance feedback on multiple indices.

These tables include only action-logics that have been empirically found in managers and organizations. According to developmental theory, there is both an earlier stage of human development, the Impulsive stage (analogous to Conception), and a later stage, Ironist, at which no managers to date measure, as well as two later organizational stages, Foundational Community and Liberating Disciplines

Obstacles to Change

In the 10 organizations that we studied, all of the CEOs and many members of the senior management teams completed a diagnostic test. Five of the CEOs measured at the Strategist stage or later, and five measured at pre-Strategist stages. In all five cases in which the CEO was found to be at the Strategist stage, the organization transformed in a positive way—the business grew in size, profitability, quality, strategy, and reputation. Moreover, trained scorers agreed that these CEOs supported a total of 15 organizational transformations. Conversely, in the five cases of organizations with pre-Strategist CEOs, there were no organizational transformations, and, in three cases, the organization experienced crises and highly visible performance blockages.

BARRIERS TO ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGE

What happened in the two anomalous cases, where the organization changed for the better but the CEO was evaluated at a pre-Strategist action-logic? When we researched that question, we found something quite interesting: In both instances, the CEO had treated an outside consultant and one or more team members, all of whom measured as Strategists, as close confidantes. For instance, in one of the not-for-profits, the CEO worked unusually closely with a consultant for several years, inviting his influence in all aspects of the operation of the senior management team. This CEO also promoted one Strategist manager to senior management and highlighted the work of another in a way that increased the influence of that work over the whole organization.

By contrast, in the three examples in which the organizations did not transform in a positive direction, the pre-Strategist CEOs had increasingly distanced themselves from the consultant and from senior management team members who measured at the Strategist stage or later. In one case, the CEO alternated between, on the one hand, highly valuing his internal consultant/senior manager and the change process and, on the other hand, trying to displace her from the senior management team altogether while freezing the change process. Not surprisingly, the organization did not transform during this period.

Leverage Points for Organizational Development

So, what do the results of this study mean for other organizations that may be embarking on, or are in the midst of, a transformation process? First of all, they indicate that any business that is serious about organizational transformation should carefully consider the significance of the CEO’s role. Our results challenge common assumptions such as, “Change can start anywhere in the organization” or “Bottom-up change is what we want.” At least initially, the CEO’s informed support is necessary in order to create a culture in which anyone in the organization can initiate change.

Second, if the CEO is unwilling to assume a leadership role in the transformation or is unable to accept feedback from others, our results support raising this issue with him or her as early as possible to highlight the potential impact of this behavior on the change process. Different CEOs are likely to respond as differently as the two vice presidents in the earlier story (and here it is relevant to add that other members of that senior team had incorrectly predicted which VP would choose a learning response and which would resist the change effort).

Third, the results of this study indicate the usefulness of diagnosing the current developmental actionlogic of the organization as a whole in order to understand the challenges it faces and to outline strategies for moving to the next level. Certainly, we as consultants did so in each case and tested our tentative diagnoses and strategic prognoses with members of the organizations. We found that our diagnoses gained us legitimacy and helped focus the transformation process.

Fourth, developmental theory holds that a person operating from a later action-logic can play a positive role in supporting the transformation of a person or organization at an earlier stage of development. Thus, a CEO at the Achiever stage can help an organization at the Experiments stage or earlier to transform. Likewise, as we found in the two organizations that transformed without the guidance of a Strategist CEO, a preStrategist CEO may successfully partner with others from within or outside the company to support organizational learning.

Fifth, members of the senior team can engage in a self-diagnosis process (with the help of the references listed at the end of this article), or they can solicit outside assistance to evaluate the current level of individual and organizational development. At first blush, it may seem unacceptably risky to attempt two change processes — of senior management team members and of the organization — at the same time. Why not work first with the senior management team and later with the wider organization? This may be possible and preferable in some cases, but often the organizational and environmental conditions that call for transformation will brook no delay. Also, staff members’ awareness that the CEO and senior managers are facing the same vulnerabilities, uncertainties, and experiments as

Staff members’ awareness that the CEO and senior managers are facing the same vulnerabilities, uncertainties, and experiments as they are can become a potent force for widespread buy-in.

they are can become a potent force for widespread buy-in.

Finally, the five disciplines, accompanied by mentoring, journal keeping, meditation-in-action, and reflective, multicriteria performance assessments, are all ways of moving from one developmental action-logic to the next. Organizational retreats to engage in “systems experiencing” across the four territories of assessing, performing, strategizing, and visioning can sometimes transform the actionlogic of an organization in a single weekend.

Engaging in Transformation

So far as we know, these are the only 10 cases in which the developmental action-logic of senior managers and its effect on organizational transformation have been studied. Our results suggest that leaders who use power in a mutually transforming manner can help an organization evolve through earlier stages up to the Collaborative Inquiry stage, where organizational learning is likely to flourish.

Developmental theory shows that, rather than defending against change, true learning leaders and learning organizations are continually engaged in the transformation process. In the face of perpetual transition, the great challenge is how to engage in both productive activities and thoughtful inquiry over the short and longterm. This process entails interweaving these two key elements in the organization’s vision (e.g., SAS airlines’ motto “moments of truth”), in its strategies (e.g., 3M’s formula for linking a division’s funding to the percentage of its ROI that comes from recent innovations), in its operations (e.g., meetings that encourage frank inquiry and dialogue as well as decisiveness), and in its assessments (e.g., 360-degree feedback).

This transformational learning challenge is at least as great as the struggle to gain unilateral political, economic, and technological control over nature and society that has preoccupied us for the past 500 years. As more and more of us become aware of the dignity of mutual, transformational partnerships, rather than unilateral, exploitative relationships, within organizations and polities, between men and women, and between society and nature, we will become increasingly inspired to devote our daily lives to these means and these ends.

David Rooke is a partner of Harthill Group Consultants in England. William R. Torbert currently serves as professor of management at the Carroll School of Management, Boston College (torbert@bc.edu). A detailed description of the methods and statistical results of the study described in this article can be found in D. Rooke and W. R. Torbert, “Organizational Transformation as a Function of CEOs’ Developmental Stage,” Organizational Development Journal, Vol. 16 No. 1, Spring 1998.

For Further Reading

Fisher, D., and W. R. Torbert. Personal and Organizational Transformation: The True Challenge of Continual Quality Improvement. McGraw-Hill, 1995.

Kegan, R. In Over Our Heads: The Mental Demands of Modern Life. Harvard University Press, 1994.

Miller, M., and S. Cook-Greuter. Transcendence and Mature Thought in Adulthood: The Further Reaches of Adult Development. Rowman & Littlefield, 1994.

Torbert, W. R. The Power of Balance: Transforming Self, Society, and Scientific Inquiry. Sage, 1991.

Wilber, K. Sex, Ecology, Spirituality: The Spirit of Evolution. Shambala, 1995.