In my previous article, Confessions of a Recovering Knower(The Systems Thinker Vol. 16, No. 7), I described my journey from being a knower to being a learner and a framework that delineates the difference between the two. At one end of the learning continuum are knowers. They adopt a mental stance that they know all that they need to know in order to address the current situation. Their self-esteem is closely tied to their ability to know, be right, and not be blamed. At the other end of the continuum are learners, who have taken a mental stance that allows for them to be influenced, “not know,” and admit that they don’t currently have the ability to achieve their desired results.

Organizations can use this framework to create a personal development path an employee might pursue using the five disciplines, as described by Peter Senge in The Fifth Discipline(click here for “Shifting from Knowing to Learning”). With this framework, employees will be able to understand what progress feels like moving from reacting toward creating, from protection toward reflection, from “my part” toward “the whole,” and so on.

At Gerber Memorial Health Services (GMHS), we have invested heavily in organizational learning, providing training and support to our leaders, along with implementing some structural changes that ensure that we use these ideas in cross-departmental teams. But until we incorporated the “knower to learner framework,” we only had vague expectation for leaders to improve their skills by practicing the five disciplines. Now, we are clear on what successful development along the continuums looks like, and we are holding leaders accountable for that development.

But there is still another problem. Even if our leaders successfully developed themselves in the use of the five disciplines, they still sometimes achieved mediocre results. Through the use of a framework called “the Learner’s Path,” we have found a way for people to ensure that they tie their learning to actual results.

The Five Learner’s Path Questions

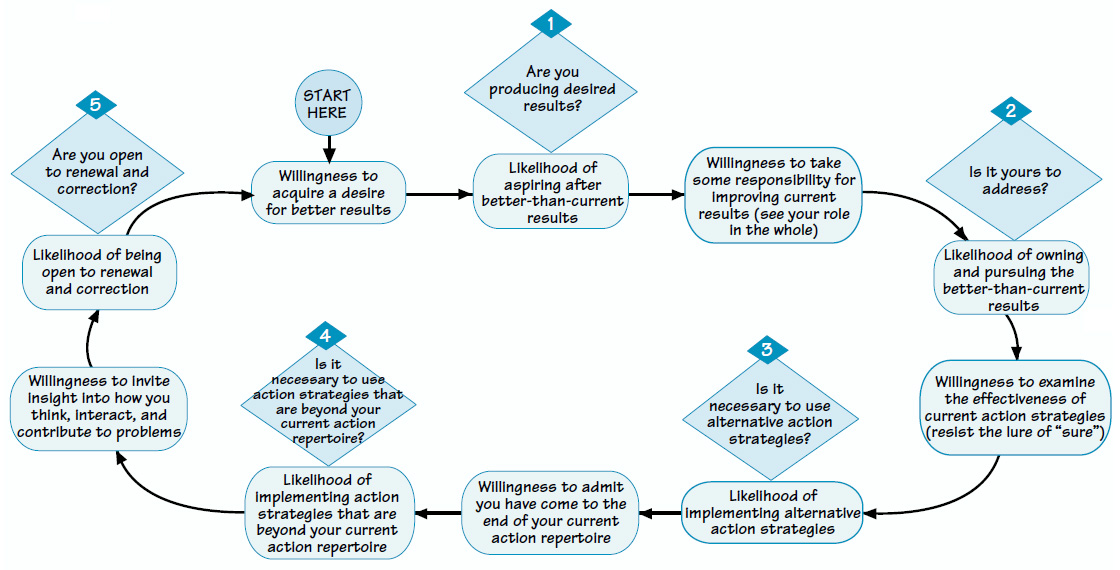

The Learner’s Path utilizes a five-question framework that leads the learner toward increased responsibility, ownership, and self-reflection. The five questions are: (1) Are you producing desired results? (2) Is this issue yours to address? (3) Is it necessary to use alternative action strategies? (4) Is it necessary to use action strategies that are beyond your current action repertoire? and (5) Are you open to renewal and correction?

The individual or group answers the five questions in succession. If they answer each question successfully, they increase the likelihood that learning will occur (by “learning,” I mean “increasing one’s ability to achieve desired results through effective action” and not simply the accumulation of more information in one’s head). When you answer the first three questions successfully, you can say that you have become a learner, and not before. Affirmatively answering questions four and five will, thereafter, deepen your learning.

The Anvil of Learning

We might think of these five questions as the “anvil” against which we shape and form our knowledge. Imagine a blacksmith trying to shape a piece of metal into something valuable and useful without the use of an anvil. He holds the metal to be shaped in one hand while holding the sledgehammer in the other. With no base on which to rest the metal piece, he grips it as tightly as he can while clanging the hammer against it with the other hand. The blows fall at odd angles and have little impact on the piece of metal. But when the blacksmith rests his piece of metal on an anvil, it gives him the stability and leverage he needs to form and change the metal into something useful and valuable.

This same principle is true of any learning effort: When you attempt to learn without the support and testing of the anvil of learning, you are unlikely to transform your learning into something useful and valuable namely, an ability to achieve the results you couldn’t achieve before. Just as the anvil significantly leverages the blacksmith’s effectiveness, so the Learner’s Path leverages the learner’s effectiveness.

Blacksmith-The-Anvil-of-Learning

Walking Along the Learner’s Path

Let me illustrate how to use this framework with a story. I facilitated a meeting of a group of leaders, who were discussing the possibility of implementing a large-scale customer service improvement strategy. Customer service scores had been flat for two years, and some people advocated for doing something new to improve the scores.

I started out by explaining that I would be walking them through the Learner’s Path/Five Questions framework, which would help them determine what level of learning would be necessary for the initiative. Then, I led them through a progression of the five questions, as follows.

1st Question: “Are you producing desired results?”

After reviewing the trends of flat scores (although at a very high level) over the past two years, they concluded that these scores were not good enough. They wanted to be known for something better than “customer satisfaction” they wanted to give their customers “profound experiences.” Had they said that they were satisfied with the current results, there would be no point for them to continue the conversation. The rest of the five questions would be a waste of time unless they felt some aspiration to improve current results.

2nd Question: “Is it yours to address?”

In other words, they had to decide if they, as leaders, ought to take some responsibility for addressing this issue. They said, “If we don’t take responsibility, who will? What is the alternative?” Again, had they said that they did not want to assume responsibility, the conversation would have stopped, and the group would have had to be content with some wishful thinking that someone else would do something about improving the customer scores.

THE LEARNER'S LOOP

The purpose of The Learner’s Loop is to articulate what capacities a person must develop in order to increase their chances for successfully answering each of the five questions. Progressing along the Learner’s Path is not a linear process; it is a closed loop, an engine of growth, around which a learner circuits, seeking continuous development.

3rd Question: “Is it necessary to use alternative action strategies?” This question forced the group to struggle with some dilemmas. If they said, “No, we can keep using the current strategy,” then I would have had to ask why they hadn’t actually produced profound customer experiences all along. Alternatively, if they believed they should use some type of alternative action strategy, they would have to admit that their current strategy hadn’t worked, which could be threatening or embarrassing to them. In this case, the leadership group decided that they needed to try an alternative action strategy. Again, had they said “no,” there would have been no point in continuing the conversation because they would not be convinced that they actually had anything to learn.

4th Question: “Is it necessary to use action strategies that are beyond your current action repertoire?” At this point, the group answered “yes.” They felt that, if they were to achieve profound customer experiences, they would have to implement an action strategy that they did not yet know how to implement. In other words, they would have to expand their current action repertoire (by “action repertoire,” I mean action strategies they could reliably use to achieve desired results). Had they said “no” to this fourth question, the group would have assembled another action strategy from their current repertoire and, in the process, would be less likely to succeed.

5th Question: “Are you open to renewal and correction?” Without hesitation, the group said “yes” to this question. Because I doubted whether they really understood the implications of this answer, I clarified that this meant they would have to look closely and deeply at themselves regarding how they think, interact, and/or contribute to the current situation. They still said “yes.” They understood that they would be required to examine how their leadership had contributed to the flat scores.

As a result of walking along the Learner’s Path together, the leaders knew that, in order to achieve profound customer experiences, they would have to dramatically change the way they led the organization. They knew that it would not be enough just to do more of the same thing or to do the same thing better than before. They would have to learn to do new things and that this approach would require an openness to renewal and correction. The group used the five questions as an anvil against which they changed and formed their idea of the kind of results they wanted and the kind of learning that would be required of them in order to achieve those results.

Smoothing Out the Path

These five questions are deep and challenging when they are taken seriously. They are particularly difficult, and often threatening, to someone operating from a knower stance. How can knowers be helped to overcome their fear and sense of threat about answering these questions? The Learner’s Loop can help (see “The Learner’s Loop”).

The purpose of The Learner’s Loop is to articulate what capacities a person must develop in order to increase their chances for successfully answering each of the five questions. These capacities are described as a matter of “willingness” is the person willing to take the necessary action to increase the likelihood of answering one of the questions successfully?

Progressing along the Learner’s Path is not a linear process; it is a closed loop, an engine of growth, around which a learner circuits, seeking continuous development. You will notice that there is a suggested order for the first rotation, and then the loop feeds on itself thereafter.

At GMHS, we have designed a curriculum geared toward helping individuals increase their willingness to take the necessary actions and, thereby, increase the likelihood that they will successfully answer the Learner’s Path questions. I will describe below why these “willingnesses” are important and suggest some organizational learning tools, techniques, and frameworks that can be used to increase them.

1. Willing to Acquire a Desire We are more likely to aspire for better-than-current results (successfully answer question #1) when we are willing to acquire a desire to improve current results. If we are totally content with our level of current results, we will feel no prompting to seek new learning at all. Sometimes, people truly are achieving all that they could imagine in a certain area, and, in that case, they should move on to other issues. At other times, people delude themselves into thinking that current results are acceptable, when everything and everyone around them is screaming for better performance. The disciplines of personal mastery and shared vision are key in stoking the fires of desire for improved results.

Organizations investing in their capacity for organizational learning should design their curriculum so that learners:

- Increase their self-awareness (e.g., Myers/Briggs, DiSC, etc.).

- Uncover their personal values and vision (e.g., personal mission statements).

- Work from a creative, not a reactive, orientation (e.g., The Path of Least Resistance by Robert Fritz).

- Empower their actions with creative tension (e.g., The Path of Least Resistance by Robert Fritz).

- Co-create collective aspiration (e.g., shared visioning).

2. Willing to See Your Role in the Whole

We are more likely to own and pursue better-than-current results (affirmatively answer question #2) if we are willing to take some responsibility for seeing our role in the whole scheme of things. Systems thinking is most often thought of as a discipline for analyzing and solving difficult problems and it is useful for these things. It is also helpful for changing our perspective about who should be responsible for addressing problems in the first place.

Those organizations investing in their capacity for organizational learning should design their curriculum so that learners:

- Understand how structure influences behavior (e.g., the Iceberg diagram).

- See life as dynamic, complex, and interdependent (e.g., the concepts and tools of systems thinking).

- No longer see problems as “out there” (e.g., causal loop diagrams).

3. Willing to Resist the Lure of “Sure”

We are more likely to implement alternative action strategies (affirmatively answer question #3) if we are willing to examine the effectiveness of our current action strategies and resist the lure of being sure that we have the right strategy. Knowers are particularly resistant to this examination, for fear that it will be revealed that they didn’t actually know the best action strategy after all. If we are open to considering multiple perspectives, being unsure, or admitting our knowledge is less-than-complete, then we will be more willing to experiment with alternative action strategies and learn how to effectively improve current results.

The practices of the discipline of mental models are especially helpful at this point along the Learner’s Path, and a curriculum designed to teach skills in this area should enable learners to:

- Consider multiple perspectives (e.g.,the story of the blind men and the elephant).

- Examine their thinking and assumptions (e.g., the Ladder of Inference and Left-hand Column).

- Pursue mutual understanding using “reflection mode” rather than “protection mode” conversations (e.g., AND Stance, 3rd Story, “Be in control” vs. “Mutual learning” model).

- Realize that “me” and “my view” are not the same thing (e.g., “I Am Not My Hat”).

4. Willing to Raise the Bar of Your Action Repertoire

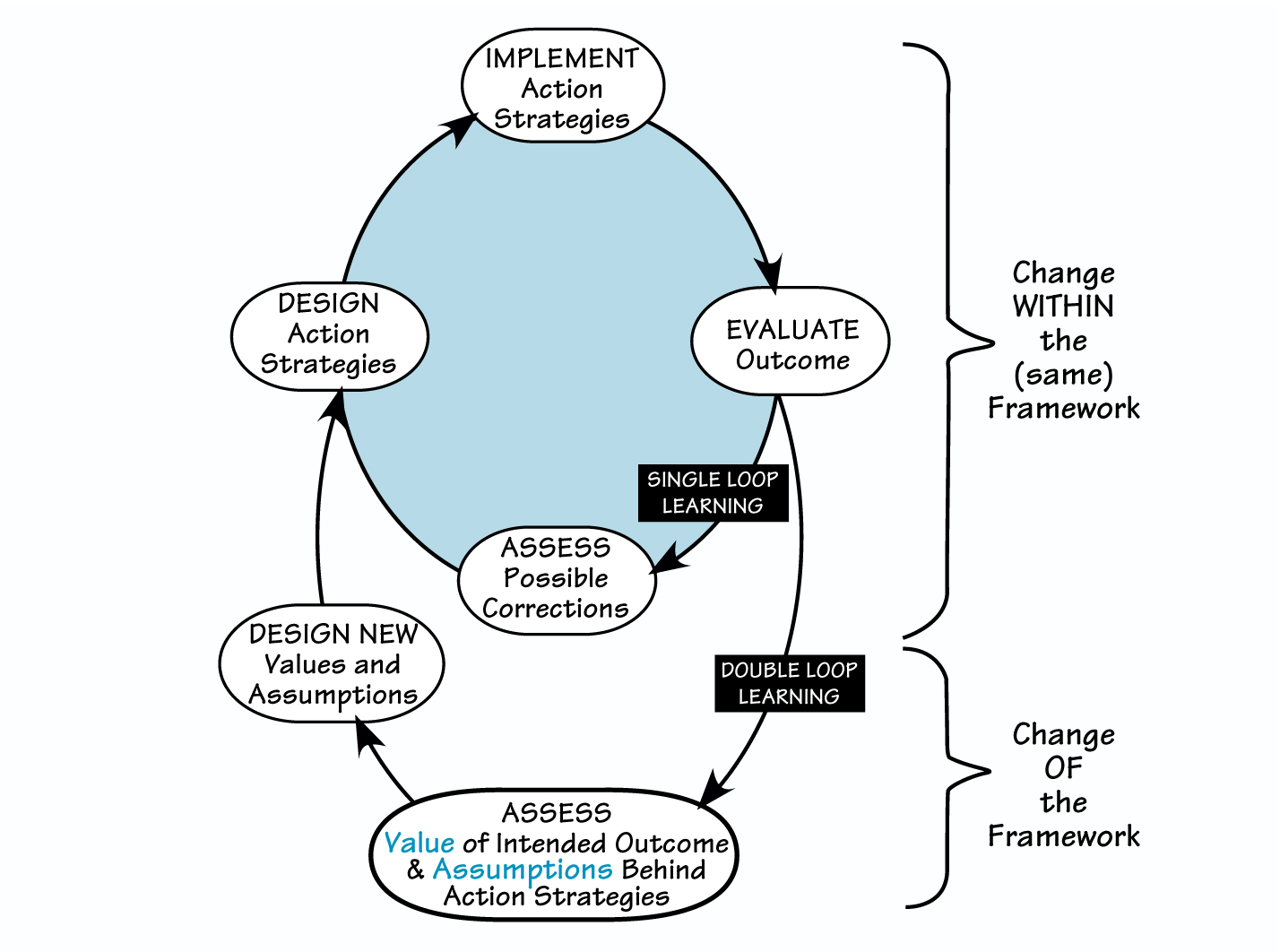

We are more likely to consider new action strategies beyond that which we currently know how to implement (affirmatively answer question #4) if we admit we have come to the end of our current action repertoire and want to expand it. Up to this point, as learners, we have used “what we know” to achieve “what we can.” This incremental type of learning is called single-loop learning, and it will only bring us so far — never producing breakthrough results. To expand our action repertoire, we need to examine and challenge the mental framework under which we are doing our learning. This kind of deep learning is called double-loop learning (see “Double-Loop Learning Cycle”).

The group-oriented discipline of team learning is particularly helpful here. We need the help of others to confirm that we have, indeed, reached the end of our capabilities and to have frame-breaking conversations. A curriculum teaching this capacity should enable learners to:

- Implement double-loop learning (see “Double-Loop Learning Cycle”).

- Create the conditions for effective group learning (e.g., Four-Player Model, ground rules from The Skilled Facilitator by Roger Schwarz).

- Generate new insights (e.g. productive conversations, dialogue).

5. Willing to Invite Insight We are more likely to be open to renewal and correction (affirmatively answer question #5) if we are willing to invite insight into how we think, interact, and contribute to problems. Doing new things in new ways and getting better results is an exhilarating and challenging learning experience. But we may still find ourselves reacting to problems rather than creating fundamental solutions; trying to get compliance from others rather than commitment; protecting ourselves during conversations rather than reflecting on our conversational habits; focusing on “my part” rather than on “the whole”; and getting into debates rather than engaging in mutual learning. Advanced learners are continually seeking deep change in themselves as they move along the continuums of the five disciplines toward the learner stance.

Again, this is where team learning is particularly helpful, along with a renewed emphasis on personal mastery. A curriculum teaching this capacity should, additionally, enable learners to:

- Integrate all five disciplines into everyday practice (e.g., action learning projects).

Pursuing the “Trade” of Learning

Blacksmithing is a learned trade. No one could ever attend a three-day workshop and return as a master blacksmith. It takes years of apprenticeship and continual practice. It is not glamorous work, but consider the impact the blacksmith has had on the world. “When the first blacksmith began hammering on a hot piece of iron, little did he know how he was shaping the future. He forged the tools that made the machines that produce everything mankind has today. The blacksmith was the pioneer of the technology that carried mankind from the iron age to the space age. It can truly be said that the first rocket to the moon was virtually launched from the face of the anvil” (Bill Miller, theforgeworks.com).

Just as a blacksmith forms and shapes his metal objects using a hammer supported and leveraged by an anvil, let us shape and form our knowledge using the hammer of the Knower-to-Learner framework and the anvil of the Learner’s Path. By doing so, we develop our capacity for learning and tie our knowledge to actual results.

Like blacksmithing, the “trade of learning” cannot be learned quickly and is not always glamorous. Nevertheless, consider the impact that it can have on our world. Responding to a changing world without deep, intentional learning is a risky proposition. Will it truly be said that the future we created together was formed on the face of the anvil of learning?

DOUBLE-LOOP LEARNING CYCLE