In December 2002, the entire world was arguing about what to do about Iraq. There were two sides to the argument. On one side, most of the world’s leaders and most of the countries on the United Nations Security Council argued that we needed to keep talking, with each other and with the Iraqis, to try to find a peaceful solution to this tough, complex problem. On the other side, the U. S. government and its allies argued that talking could not work and that force was the only way to solve this problem. The second side prevailed, and the war started.

If you’re not part of the problem, then you can’t be part of the solution.

– Bill Torbert

While this was happening, I was at my home in South Africa working on a book about how we can solve such tough, complex problems through open-minded, open-hearted talking and listening. Then my youngest stepdaughter, who is 27 years old, came home for the holidays and immediately lapsed into her old teenage behavior. She would go out without telling us, stay out partying until late, and sleep away the day. One evening she had spent hours on the phone having a weepy conversation with an old boyfriend. I was furious! I told her that this kind of behavior was absolutely unacceptable and that she needed to change what she was doing if she wanted to use my phone and stay in my house.

That approach didn’t work. The next morning she left and went to stay with her sister. I had managed to do in my own home what the Americans were doing in Iraq. I had tried to solve a tough problem by using authority: by force.

Why is it that we so often end up trying to solve our tough problems by force? Why is it that our talking so often fails? The answer is both simple and at the same time subtle and challenging. Our most common way of talking is telling, and our most common way of listening is not listening. When we talk and listen in this way, we guarantee that we will end up trying to solve our tough problems by force.

Two Distinctions for Solving Problems

I would like to offer two sets of practical distinctions that you can use to solve your tough problems more effectively. The first distinction is that there is more than one way to solve problems. There is an ordinary approach that works for simple problems, and there is an extraordinary approach that works for complex problems. The second distinction is that there is more than one way to talk and listen. If we are to solve our tough problems peacefully, we need to learn an extraordinary way of talking and listening.

I will explain these two distinctions by sharing two dramatic, life and-death stories. I’m not that sensitive to these distinctions, and so the volume has to be turned way up if I’m going to be able to hear them. These two stories involve situations in which the volume was turned way up, but the two sets of distinctions apply to all human settings—home, school, work, meetings, and national and international affairs.

I learned the first set of distinctions in 1991. I was living in London working for Royal Dutch/Shell’s scenario planning department, heading the social-political-economic research group. Our job was to tell stories about what might happen in the world outside the company, as a tool for Shell executives to use in making decisions today that would allow the company to do well no matter what happened tomorrow. One day, my boss, Joseph Jaworski, received a phone call from a professor in South Africa named Pieter le Roux, who wanted to use the Shell scenario methodology to help make plans for the transition in South Africa away from apartheid. Pieter was wondering if Shell could send somebody to provide methodological advice to the team he was putting together and to facilitate the workshops.

When I was chosen for this project, I knew almost nothing about South Africa, except that the country had a complex problem of apartheid, which most people thought could not be solved peacefully. I knew that the white minority government had been trying for years to deal with the situation by force and had failed, and that the opposition, led by the African National Congress, had tried to over throw the government by force and had failed. I was also aware that Nel- son Mandela had been released from prison a year before and that some negotiations were starting. But I didn’t know much about the scenario team Pieter had put together, except that it was very diverse and included blacks and whites, people from the left and right, professors, political activists, businessmen, establishment figures, trade unionists, and community leaders. I also knew that these people were heroes who had all, in different ways, been trying for a long time to make South Africa a better place.

Since I was very busy with my work at Shell, I didn’t do what I normally would have done: read up on South Africa and form my expert opinion about what was going on and what they ought to do about it. Not having had the time to form such an opinion, I arrived with a greater openness to what this amazing team was going to be able to do. I had also never done this kind of work outside of a company, so we simply used Shell’s scenario methodology. The team immediately launched into discussions about the ANC, the NP, the PAC, the SACP, the CP, and the UDF. I had no idea what they were talking about. One of the team members later said to me, “Adam, when we first met you, we couldn’t believe that anybody could be so ignorant. We were certain you were trying to manipulate us. When we realized that you actually didn’t know anything, that’s when we decided to trust you.” I had, by accident or synchronicity, managed to arrive with the perfect orientation: curious, respectful, and open.

What I came to understand in South Africa was that two parallel processes were occurring. There were the formal, official negotiations around a new constitution, which the newspapers reported about daily. But underneath these were hundreds of informal, unofficial meetings, such as the one I participated in, that brought together all the stakeholders—all the people who were part of the problems—to talk together about the problems and what ought to be done about them. It was through these myriad informal conversations that the formal process succeeded.

I also noticed that, even though we were using the exact same methodology as at Shell, the South African group brought a different energy to the work. In one way it was more serious, and in another more playful. What I eventually understood is that although the methodology was exactly the same, the group’s purpose was fundamentally different. At Shell we had been telling scenarios about what might happen as a tool to help the company adapt as best as it could to whatever might occur in the future. In the South African team, we were telling scenarios not so much to adapt but to create a better future. And this is what accounted for the different energy in the team.

Three Types of Complex Problems

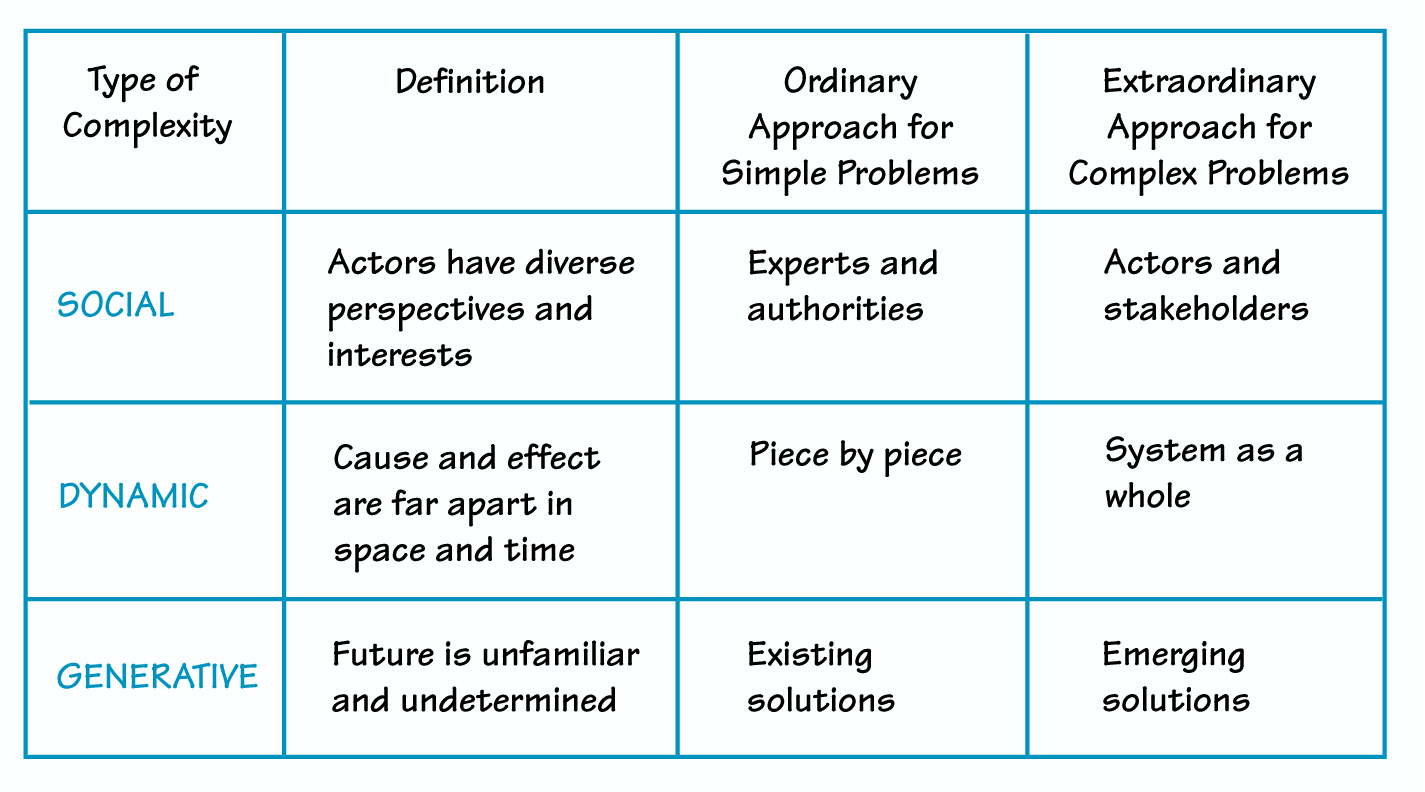

So here’s what I learned in South Africa: a problem can be tough and complex in three different ways.

Socially Complex. A problem is socially complex when the people involved, the actors in the system, have highly diverse perspectives and interests. Problems that are socially simple can be solved by experts and authorities, because it’s easy to agree on what the problem is and for an expert or a boss to propose and implement a solution that people will support. But a socially complex problem cannot be solved without the direct participation of all the stakeholders involved.

Dynamically Complex. A problem is dynamically complex when its cause and effect are far apart in space and time. This is the kind of complexity that is addressed by systems thinking. A dynamically simple problem can be solved piece by piece, but when dynamic complexity is involved, we have to look at the behavior of the system as a whole.

Generatively Complex. When a problem is generatively complex, the future of the system is unfamiliar and undetermined. A generatively simple problem can be solved using rules of thumb from what worked in the past. But when the problem is generatively complex, it can only be solved through a group of people working it through together, listening for and trying out emerging solutions.

TWO WAYS TO SOLVE PROBLEMS

A problem can be tough and complex in three different ways; it can be socially, dynamically, and/or generatively complex. Ordinary problem-solving approaches work well for simple challenges. But when we want to solve complex problems, we need to use an extraordinary approach, in which stakeholders look together at the system as a whole and work through an emerging solution.

To give you an idea of how this problem-solving model works, let’s look at the simple matter of a police officer directing traffic at a difficult intersection. The problem is socially simple because everybody has the same objective: to get through the intersection safely and efficiently. The problem is also dynamically simple because all the causes and effects are right there, visible and immediate.

And it’s generatively simple because the way the officer directs traffic, based on what he or she learned at traffic-directing school, works fine. So the problem can be solved using the ordinary approach.

The ordinary approach works perfectly well most of the time. It’s when we want to solve complex problems that we need to use an extraordinary approach, in which the people who are part of the problem— the stakeholders—look together at the system as a whole and work through an emerging solution. This is what I realized the Mont Fleur team had done in South Africa. They had gathered leading representatives from all of the stakeholder groups and used sce- nario planning as a tool for thinking about the behavior of the whole system and finding emerging solutions. My point here is that the ordinary approach cannot generate a peaceful solution to a complex problem. If we use the ordinary approach on a complex problem, we will end up trying to solve the problem by force.

I understood the significance of this realization in my work in South Africa, where people were experimenting with an extraordinary approach to solving complex prob- lems that was applicable not just to the South African context, but else where as well. What I didn’t understand, because I was not experienced enough, is how the South African team was able to work with this extraordinary approach. In the years that followed, I got a lot of experience with this methodology through doing this kind of work with multistakeholder teams in South Africa, Northern Ireland, Israel, Argentina, Colombia, the United States, and Canada. I also began to develop, with colleagues, a family of tools for working with important complex problems in companies and governments.

It wasn’t until 1998, however, in the course of doing some work in Guatemala, that I really grasped the essence of how a group could use the extraordinary approach. I don’t know how well you know the story of Guatemala. It has the dubious distinction of having had the longest running and most brutal civil war in all of Latin America. Over a 36-year period, from 1960 to 1996, more than 200,000 people were killed and disappeared out of a population of only 8 million. More than a million people became internal refugees, and the country as a whole experienced a brutality such as humanity has rarely seen. By the time the peace treaty was signed in 1996, the social fabric of the country had been shredded.

Many brave and wonderful efforts, which continue today, have been made to try to put things back together again. One of these efforts, inspired by the project in South Africa, was called Visión Guatemala. The Visión Guatemala group brought together a group of leaders—even more diverse and senior than the South African team—from the mili- tary, the former guerrillas, business, church, academics, and youth leaders, to try to understand what had hap- pened in the country, what was happening, and what ought to happen. Those of you who follow the news know that things are by no means all right in Guatemala, but in the five years they’ve been working together, this team has made a big impact in the country, on the platforms of all the major political parties, on restructuring the education and tax systems, on constitutional amendments, on anti-poverty programs, on dialogue processes at the municipal level and among politicians, and so forth.

Four Ways of Talking and Listening

In 2000 a group of researchers from the Society for Organizational Learning interviewed members of the Visión Guatemala team to try to pinpoint exactly what happened in their group to allow them to do such extraordinary work in such a highly complex system. The answer the researchers arrived at has to do with the way this group, over the course of their involvement together, progressed in the way they were talking and listening.

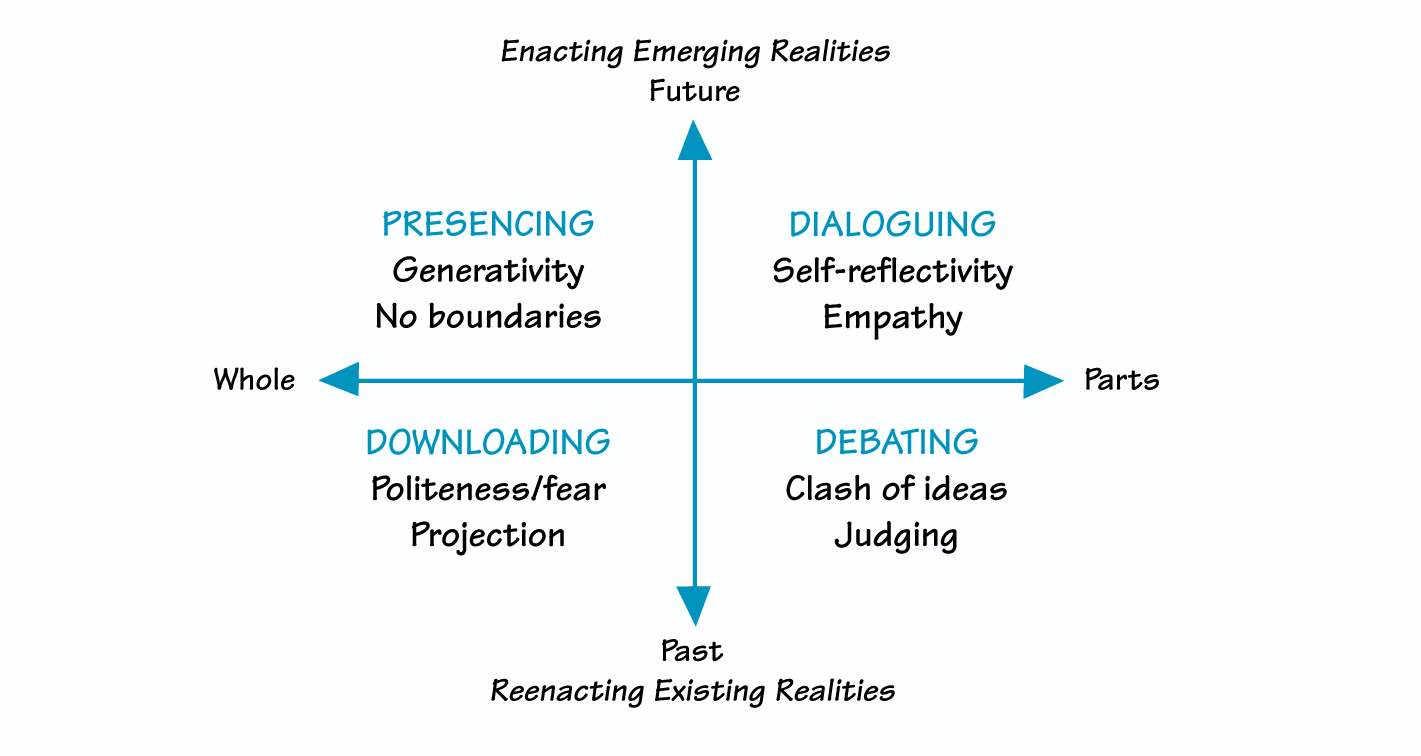

Downloading. In the chart “Four Ways of Talking and Listening” (see p. 5), based on the work of Otto Scharmer of MIT, there are four quadrants. According to the researchers’ observations, the Visión Guatemala group started their conversations in downloading. This is supported by an interview with Elena Díez Pinto, the leader of the group. She said, “When I arrived at the hotel for lunch before the start of the initial meeting, the first thing I noticed was that the indigenous people were sitting together, the military guys were sitting together, the human rights group was sitting together. I thought, ‘They are never going to speak to each other.’ In Guatemala we have learned to be very polite to each other. We are so polite that we say ‘yes’ but think ‘no.’ I was worried that we would be so polite that the real issues would never emerge.”

This first type of talking and listening is called downloading, because we merely repeat the story that’s already in our heads, like download- ing a file from the Internet without making any change to it. I say what I always say or what I think is appropriate, such as “How are you? I’m fine,” because I’m afraid that if I say what I’m really thinking, something terrible will happen, for instance, I’ll be embarrassed or even killed. Listening in downloading mode is not listening at all. I am only hearing the tape in my own head.

Debating. The second kind of talking and listening is called debating. A wonderful example of this process occurred in Visión Guatemala’s first workshop. One of the interviewees said, “The first round in the first session was extremely negative, because we were all looking back to the events of recent years, which had left a deep imprint on us. Thus a first moment full of pessimism was generated. Suddenly a young man stood up and questioned our pessimism in a very direct manner. This moment marked the beginning of a very important change, and we continually referred to it afterward. That a young man would suddenly call us ‘old pes- simists’ was an important contribution.” This was debating in the sense that the young man was saying what he really thought, which is what happens when people make the transition from downloading to debating. A clash of arguments occurs; ideas are put forward and judged objectively as in a courtroom.

I used to undervalue debating because it seemed so commonplace. But in the last few years, through observing how many countries and companies in which I’ve worked stay in downloading mode, where people are afraid to say what they think, I’ve come to appreciate the move from downloading to debating as a huge step forward. You can see more perspectives, that is, more of the system.

However, in debating as well as downloading, you’re still seeing what is already there. Neither of those modes creates anything new. For example, in a debate or a courtroom, people have prepared what they want to say before they even enter the room. In that sense, both download- ing and debating lead to a reenactment of patterns of the past or of existing realities. To bring forward something new, we need to talk and listen in an extraordinary way.

Dialoguing. The third mode is called dialoguing. My favorite example of this in the Visión Guatemala team occurred one day when the group was talking about an extremely difficult subject: the civil war in which hundreds of thousands of people had been killed. A general in the army was trying to explain honestly what the war had looked like from his experience and perspective, which was both a very difficult and an unpopular thing for him to do. He certainly did not have the sympathy of most of the people in the room. As he spoke, the woman listening beside him, Raquel Zelaya, the cabinet secretary of peace who was officially responsible for implementing the peace accords, leaned over to him and said, “Julio, I know that nobody enrolls in a military academy in order to learn how to massacre women and children.”

FOUR WAYS OF TALKING AND LISTENING

Downloading and debating work fine for solving simple problems, but they don’t work for solving complex ones. For complex problems, groups need to use dialoguing and presencing, and to be able to shift from one mode to another, as appropriate.

This was a remarkable statement. On the one hand, she was signaling that she had been listening to him with empathy, listening from his perspective and realizing that no matter what had happened, he certainly hadn’t started out his life with a brutal intention. At the same time, through self-reflection, she was indicating her understanding that the way she thought about things mattered and affected how this situation would unfold. In other words, if you cannot see how what you’re doing is contributing to creating the current reality, then by definition you have no leverage, no place to stand, no way to intervene to change the problem situation. When Raquel made that comment to the general, she was recognizing the way in which herat titudes were part of the polarization and needed to change to open up a new way forward.

So in dialoguing, I am both listening to you from within you and listening to myself knowing where I’m coming from. I am not just listening objectively to ideas; I am listening subjectively from inside you and me. And because I’m listening from inside a living, growing system, I can glimpse what’s possible but not yet there. This type of talking and listening is the root of the potential forchange and creativity.

Presencing. This fourth type of talking and listening is what Otto Scharmer, along with Joseph Jaworski, Betty Sue Flowers, and Peter Senge, has written a book about, which is due to be released this winter and is titled Presence. For that reason, I am using the word presencing, because what I am referring to is the particular kind of talking and listening, of being and doing, that they describe in their book. In the Visión Guatemala group, we experienced this kind of generative dialogue one evening at the first workshop. The group had gotten together after dinner, and I had asked the participants to tell stories about their experiences, either recent or long ago. The exercise was a continuation of the scenario work of trying to understand what had happened and what was happening in Guatemala. But rather than use systems thinking as an objective tool to identify driving forces and key uncertainties, we were using amore subjective approach.

It was a dramatic evening. Helen Mack Chang, a prominent business woman, spoke about the assassination of her sister, a researcher, in broad day-light in Guatemala City some years before. She shared her experience of that day, after her sister had been murdered, and how she had run from government office to government office, trying to find out what had happened, and how the first person she had spoken to, who had lied to her and told her that he knew nothing, was the man sitting beside her that evening in the circle. We were long past being polite. Now people were really saying what they thought.

Then a man named Ronalth Ochaeta told a story. Ronalth was at that time the executive director of the Catholic Church’s human rights office, which published the very important first report on the civil war called “Nunca Más” (, “Never Again”). He spoke of how he had gone one day to be the official observer at the exhumation of a mass grave in a Mayan village. There were many such graves. As he stood by the side of the grave and watched the forensics team removing the earth, he noticed many small bones at the bottom. He asked them, “What happened here? Did people have their bones broken during the massacre?” They answered, “No, people did not have their bones broken. This massacre included several pregnant women, and what you’re seeing are the bones of their fetuses.”

You can feel a little bit now the quality of the silence—the quality of the listening, the realization, the understanding—that we have in this room right now. Perhaps you can imagine what it was like to hear that story in a group of 40 people, all of whom had lived through this experience and in one way or another been implicated. It was a silence such as I had never heard. It just went on and on, for five, maybe ten minutes.

At the end of the day, we were talking about what had happened, and several people used the word communion to refer to that moment when the whole group had been part of one flesh. I remarked that I thought there was a spirit in the room, and a Mayan man said to me afterward, “Mr. Kahane, why were you surprised there was a spirit in the room? Didn’t you know that today is the Mayan Day of the Spirits?” When the SoL researchers interviewed the members of the Visión Guatemala team, six of the intervie- wees referred to those five minutes of silence as the moment when everything had turned in the team, the moment when the team understood why they were there and what they had to do.

One of them said, “As to the story that Ronalth recounted, the one that caused such a big impact, that is one story and there must be a thousand like it. What happened in this country was brutal. Thirty years . . . and we were aware of it, I was. I was a politician for a long time, and this was one of the areas that I worked in. I was even threatened by the military commissioners on account of my political work. We all suffered, but as opponents, as enemies, always from our own particular points of view. As far as I am concerned, the workshops helped me to understand this in its true human dimension—a tremendous brutality. I was aware of it but had not experienced it. It is one thing to know about something as statistical data and another to actually feel it. To think that all of us had to go through this process. I think that after understanding this, everyone was committed to preventing it from happening again.”

This is what we mean by presencing. It wasn’t that people felt empathy for Ronalth; anybody could have told that story. It was as if, through Ronalth, we had all been able to see an aspect of the reality of Guatemala that was of central importance. It was as if, in those five minutes, the boundaries between us disappeared, and the team was able to see what really mattered to them and what they had to do together. In this way, the process of moving from downloading and debate to dialoguing and presencing can be described as one of opening, of developing the capacity to hear what is trying to come through.

Listening to the Sacred Within Each of Us

I have explained two sets of practical distinctions. First, there are two ways to solve problems: an ordinary approach that works for simple problems, and an extraordinary approach that works for complex problems. But the ordinary approach does not work for complex problems, and if we use it, we will end up trying to solve the problem by force. Second, there are four ways of talking and listening.

Downloading and debating work fine for solving simple problems, but they don’t work for solving complex problems. For complex problems, we need to use dialoguing and presencing. If you want to be able to solve complex problems, you need both the awareness of these different ways of talking and listening and the capacity to move among them.

In 1998 Desmond Tutu retired as the Anglican Archbishop of Southern Africa. His successor, Njongonkulu Ndungane, wanted to hold a strategic planning workshop with the 32 bishops who would now be reporting to him. He asked me to facilitate the workshop. Although there were some tough issues to be worked out, it was a joyous meeting.

Right at the beginning, I noticed that these bishops were remarkable listeners; they seemed intuitively to understand and be able to navigate among these four ways of talking and listening. For example, when we were making ground rules for the work- shop, they seemed concerned about the danger of downloading and not listening (they might have called it pontificating). One of the bishops proposed the ground rule, “We must listen to each other’s ideas.” A second bishop said, “No, brother, that’s not quite it. We must listen to one another with empathy.” Then a third bishop said, “No, brothers, that’s not quite it. We must listen to the sacred within each of us.”

I think the bishops got it right. If we can learn to listen to each other truly, with empathy, and if we can learn to listen to the sacred whole as expressed through each of us, then we can peacefully solve even our most complex problems.