In 1992, Americans will spend $817 billion on healthcare — twice as much per capita than the average of the 24 industrialized nations of the OECD. And an estimated $200 billion will be thrown away on overpriced or useless treatments. “For a wide range of clinical procedures, on average, roughly 20 percent of the money we now spend could be saved with no loss in the quality of care” (“Wasted Healthcare Dollars,” Consumer Reports, July 1992).

Once a system that provided quality medicine in an equitable fee-for-service exchange, the current healthcare system in the U.S. has slowly fallen victim to its own structure. Various players are struggling with one another on an expensive battleground — and patients aren’t the only ones getting stung. Corporate America’s involvement and portion of the bill is at the forefront of discussion.

As cries for a major overhaul of the healthcare system have increased, policymakers have responded with a flood of proposals — over 30 new bills so far this year. An integrated approach to healthcare reform, however, must start with an understanding of the system as a whole.

Multiple Players

The healthcare system is made up of a complex, interconnected network of players. Without a common mission, each group pursues policies that are often at odds with the long-term interests of everyone involved. To understand how the system works (or doesn’t work) we need to see how the various players’ actions play out in the broader system.

Healthcare Providers. Healthcare professionals’ primary concern is that patients receive the best care available. This sets up the system for cost escalation by encouraging doctors and hospitals to provide more tests and procedures in the belief that more is better. Providers’ fear of malpractice suits further exacerbates the problem. In addition, practices such as unbundling (charging separate fees for each part of a treatment) and self-referrals (where doctors send patients to labs or facilities in which they have a personal investment) also contribute to escalating costs.

Healthcare Providers: Escalation Dynamics

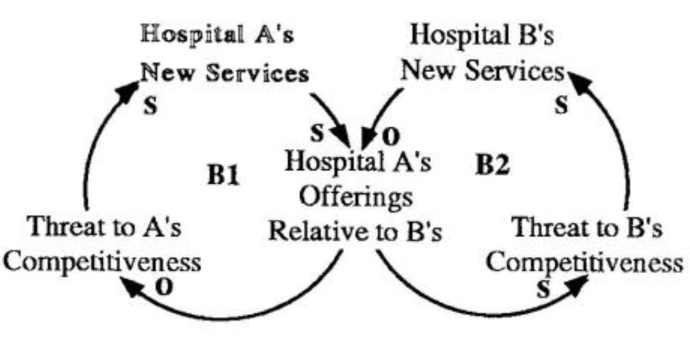

A surge in hospital construction over the last decade has also contributed to escalating costs, as hospitals scrambled to win healthcare dollars by adding state-of-the-art technology and facilities (see “The Medical Arms Race,” Systems Sleuth, November 1991 for description of escalation dynamics in healthcare). The result is an “Escalation” structure, where one hospital’s expansion efforts are seen by others as a threat to their attractiveness, prompting them in turn to add more services (see “Healthcare Providers: Escalation Dynamics”). The cost of expansion is then passed along to patients and insurers in the form of higher bills — thereby raising the total cost of healthcare.

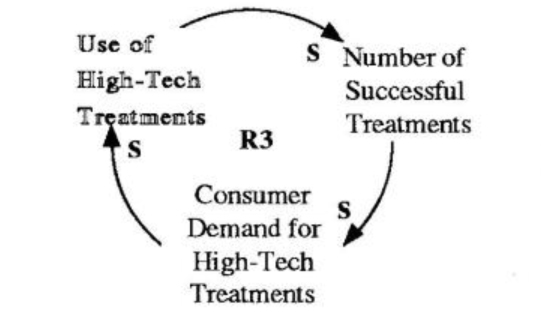

Consumers. Consumers play into the escalation dynamic through their determination to receive the best treatment, regardless of price. As hospitals add more machines and services, the success rate and public awareness of those services increases (see “Consumer Demand”). Consequently, consumers’ demand for high-tech treatment increases, which gives hospitals further incentive to add more technology. The result a system where supply actually creates demand, rather than balancing it.

Currently, there are few incentives for patients to go to the most efficient, cost-effective providers. As James C. Robinson, a healthcare economist at U.C. Berkeley puts it, “Imagine if we sold auto-purchase insurance and said, ‘Go and buy whatever car you want and we’ll pay 80 percent of it.’ Most people would probably buy a Mercedes” (“Wasted Healthcare Dollars”).

Consumer Demand

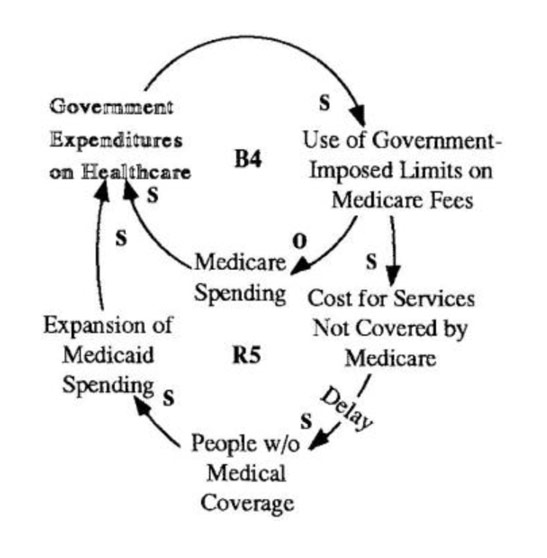

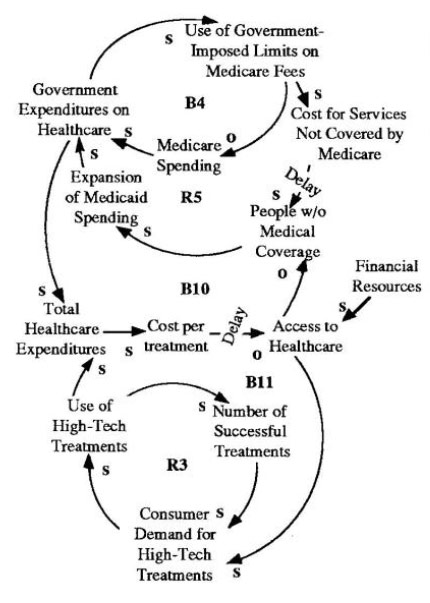

Government. The government is a major player in the healthcare system through Medicare and Medicaid programs. Their goal: to provide the highest-quality health coverage to the poor and elderly at the lowest rate to taxpayers. Efforts to curb Medicare spending, however, have inadvertently increased costs throughout the system (see “Government The Medicare Fix that Failed”). By limiting Medicare coverage, the government reduced its own spending (B4), but increased the share of the cost borne by providers. Providers, in turn, passed those costs on to patients for non-Medicare services. When those to whom the costs are shifted can’t afford to pay, they are left without coverage. This puts pressure on the government to expand its Medicaid program to absorb the additional uninsured people, which increases its healthcare expenditures (R5).

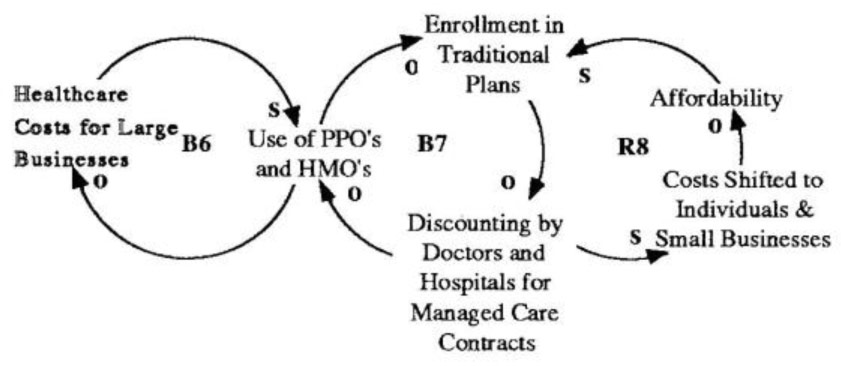

Business. Like the government, businesses have also responded to rising healthcare costs by looking for money-saving opportunities. Many large businesses are cutting costs by enrolling their employees in preferred provider organizations (PPO’s) or health maintenance organizations (HMO’s), which offer low premiums. Such managed-care organizations are designed to reduce costs through methods such as decreasing hospital usage and narrowing provider choices.

But HMO’s, although they are increasing both in membership and revenues from premiums, are hurting financially because of their very attraction — low prices. Despite a 14% increase in premiums, income from HMO’s is expected to drop to $350 million this year, from $850 million in 1991 (“An Operation Fraught With Risks,” Business Week, Jan. 13, 1992). Given this trend, premiums are likely to continue rising until there will no longer be a significant cost differential.

In the meantime, the short-term savings for businesses is increasing long-term costs for everyone in the system. As HMO and PPO membership has increased, enrollment in traditional plans is decreasing (loop B7 in “Businesses: Cost-Cutting Efforts”).

Government: The Medicare Fix that Failed

To attract healthcare dollars, hospitals will bid against each other to win managed care contracts, while doctors band together to cut deals with HMO’s, and medical supply companies offer cost-saving products to hospitals. Lost revenues from discounting will put pressure on providers to shift additional costs to individuals and small businesses who are not covered by HMO’s or PPO’s. Similar to the Medicare cuts, these higher costs will force more people out, further reducing enrollment in traditional plans (R8).

Businesses: Cost-Cutting Efforts

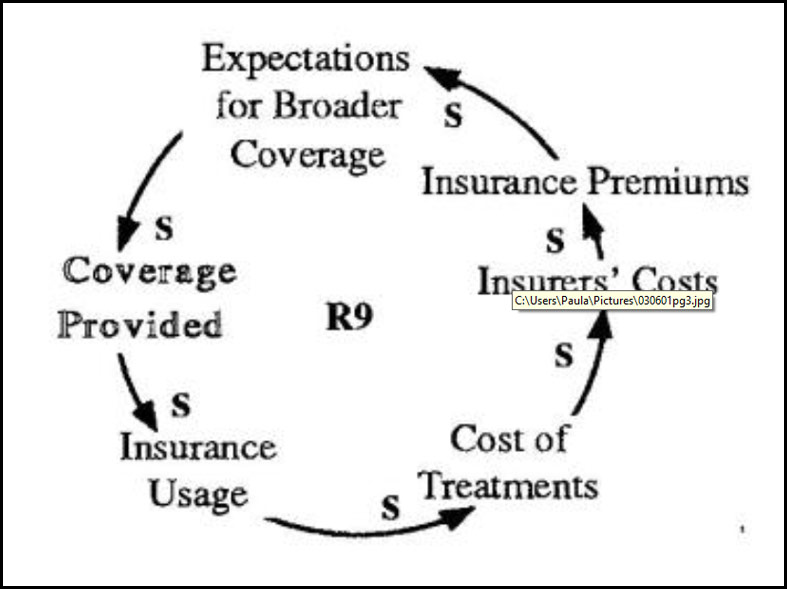

Insurers. Although healthcare insurance was originally intended to protect against catastrophic illness or accidents, over time coverage has continually expanded to attract more people (see “Insurance: Expanding Coverage”). The ever-expanding coverage gives consumers more financial incentives to seek treatments. In fact, people with health insurance consume up to 60% more physician services and three times as many hospital services than those without coverage (“Business and the Future of American Healthcare,” Business Week, June 22, 1992). As usage increases, costs rise, leading to higher premiums and demand for even more coverage and choices (R9).

PPO’s and HMO’s were designed to stop escalation by providing limited options at lower costs. As discussed above, however, the rise of PPO’s and HMO’s has come at the expense of traditional insurers and creates a “Fixes that Fail” situation.

The Big Picture

The actions taken by each of the players in the healthcare system are all contributing to a “Tragedy of the Commons” scenario, where the attainment of individual goals are at odds with the long-term health of the system. The “commons” in this case is access to healthcare, and the limiting factor is financial resources. If the present situation continues, the healthcare system may collapse because of the financial burden it places on the whole economy. Currently, more than 12 cents out of every dollar is spent on healthcare, and costs are rising at double the rate of inflation. If current trends continue, in 70 years our entire GNP will be spent on healthcare (“The Brave New World of Healthcare,” Richard D. Lamm, University of Denver, 1990).

Insurance: Expanding Coverage

Ever-expanding insurance coverage gives consumers more financial incentives to seek treatments. Higher usage increases costs, leading to higher premiums and more demand for expanded coverage.

Consumer demand for high-tech treatment and government expansion of Medicare and Medicaid play into the “Tragedy of the Commons” structure by contributing to total healthcare expenditures. This raises the cost per treatment and also limits access (loops B10 and B11 in “Healthcare’s Tragedy of the Commons: One Example”). Likewise, consumer demand for high-tech treatment also affects the “Escalation” structure between competing hospitals. As hospitals invest in new equipment and services, the cost per treatment rises, again limiting access.

The shift toward HMO’s and PPO’s plays into the “Tragedy of the Commons” structure as well. As hospitals respond to discounting by shifting costs to small businesses and individuals, the number of people who cannot afford coverage increases. Those individuals must then be covered by government programs (which increases total healthcare expenditures), or simply forego coverage and pay only that portion of their healthcare bills they can afford. The cost of those unpaid bills shows up once again in higher costs per treatment, as providers raise their rates to cover delinquent accounts.

Looking for Leverage

Current proposals for reform center around three critical problems afflicting healthcare: uncontrollable, rising costs; a lack of a long-term healthcare program, and an increasing number of uninsured and under-insured. Although the plans vary widely on details such as eligibility, acute care, preventative care, long-term care, and the role of Medicare and Medicaid, they can be grouped into three broad categories: government-sponsored (single-payer), employer-based (play or pay), and private plans (market-based reform). (See “Healthcare Reform: Evaluating the Proposals” for a discussion of how these proposals affect the dynamics described above).

Healthcare's “Tragedy of the Commons:” One Example

Perhaps the most important element of any reform is that the recipient and payer of services be more closely linked. One lesson of the “Tragedy of the Commons” archetype is that the problem cannot be addressed at the individual level. Adequate information, however, will help consumers see the “big picture” and judge the value of alternative care. No matter who pays for coverage, some link needs to be made so consumers feel the financial impact of their decisions.

From Disease Treatment to Health Building

One crucial aspect of reform that is absent from most of the current proposals is a deep change in attitudes surrounding the purpose and direction of healthcare. Most Americans believe that access to healthcare is a “right,” no matter what the cost. Not surprisingly, there seems to be more support for universal access programs than for national health insurance. Many people are afraid of non-market-based plans because of they fear a nationalized system would take away the freedom of choice and the ability to receive whatever care one can afford. But as the “Tragedy of the Commons” structure illustrates, consumers will have to learn that there are limits to everything in a finite world. One reality we all may have to face is that we can no longer expect unlimited choice and care.

How we view responsibility for an individual’s health must also change. Over time, the burden of responsibility for one’s health has shifted from the individual to the healthcare system; the implicit message has been, “live your life any way you want and we will take care of you when your body breaks down.” This gradual shift might not have been too damaging if the healthcare system were focused on helping people stay healthy. Instead, it concentrated its efforts on making treatments more effective and convenient. In a way, it is analogous to finding faster, more painless ways to repair wrecked automobiles, rather than teach people how to be safer drivers and designing better highway systems to reduce the likelihood of accidents. The result? Escalating automobile premiums, runaway costs, and a growing pool of uninsured motorists — the same problems currently facing the healthcare system.

Evaluating the Proposals

Market-based Reform. These plans are based on a simple market economy philosophy: eliminate waste and escalating costs by strengthening competition. Educating consumers on how to choose the best-priced quality care will hopefully help edge the worst providers out and provide incentives for the best to get better.

Benefits: Teaching consumers how to evaluate appropriateness and cost of treatment will hopefully break the link between continually expanding healthcare services and consumer demand for high-tech treatments (loop R3 in the “Consumer” diagram). It will also strengthen competition in the industry by helping consumers compare services across hospitals.

To break the cycle of healthcare expansions, market-reform plans propose using managed care procedures such as pre-admission certification and effective discharge planning.

Drawbacks: Critics point out the difficulty of re-educating consumers and businesses, and they question how effective managed competition will be in reducing costs. History has shown that competition in the healthcare industry can result in higher costs: according to a U.C. Berkeley study, costs per admission were 26% higher for hospitals that had more than nine competitors in a 15-mile radius.

For these plans to work, coverage for the uninsured must be addressed (loop R8 in the “Business” diagram and loop R5 in the “Government” diagram). The other challenge in market-based reforms is to carefully balance both consumer expectations and hospital expansions. If either effort fails, the system will most likely slip back into its current pattern of escalation.

Play or Pay. In Play or Pay models. Employers will have the choice of supplying insurance for their employees, or paying a 7-9% payroll tax to enroll those employees in a government-sponsored plan similar to an extension of Medicaid.

Benefits: The greatest strength in the play-or-pay proposals is their focus on reducing the number of uninsured, thereby preventing cost-shifting. Providers would no longer need to recoup Medicare shortfalls by raising prices, thereby eliminating loop R5 in the “Government” diagram. Play-or-pay plans could also reduce administrative costs through electronic insurance cards and standardized billing formats.

Drawbacks: Critics are worried that predicted costs are unrealistic; and that the projected $100 billion needed to fund the first five years of this plan would be financed by reducing Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements, actually producing extensive cost shifting (loop R5 in “Government” diagram).

Unlike market-reform plans, the play-or-pay model does not emphasize managing consumer expectation dynamics through education. By making healthcare more affordable for consumers, the plans may spur greater demand for treatments — and increase overall costs (similar to the dynamics illustrated in the “Insurer” loop R9).

Though the plan spreads the cost of health insurance over many payers, it does not take into account their relative ability to pay. Small businesses, in particular, could suffer from increased expenses. The added strain on businesses might affect the nation’s global competitiveness and companies’ ability to pay their healthcare bills.

Single-payer. The third category of proposals are government-sponsored plans, also known as single-payer plans. They not only promise universal access, but also Medicare-type benefits for every American — at a significant cost savings.

Benefits: Many supporters of these plans believe we cannot really contain costs unless one entity controls all the payments and charges. Such a plan would reduce cost-shifting and administrative burdens (eliminating loop R8 in the “Business” loops and loop R5 in the “Government” loops). It would also impose limits on services, thus preventing escalation dynamics such as rising consumer expectations and competition among providers, breaking the reinforcing dynamics in the “Consumer” and “Healthcare Provider” loops.

Drawbacks: One concern is that these systems might over-manage the cost aspect, resulting in deteriorating quality. If hospitals have no incentives to improve treatment, quality of care could suffer as the introduction of new medical technologies stagnates. Critics of the Canadian system contend that such technological and equipment shortages have affected their quality of care.

The total cost of the program, which will be financed with increased payroll and income taxes, is also a concern. Estimates range between $125 to $246 billion for the first year alone.

of cure” translates into “a dollar spent on health building may be worth thousands in hospitalization and treatment costs.” The challenge is to design a system that gets away from treating symptoms—where there is the least leverage and the highest costs—and focuses instead on efforts to build health.

The healthcare system in America is not deteriorating in a vacuum. “Health care, for all its technical genius, has become an economic cancer that is eating into other necessary public functions…Our health care industry is draining resources desperately needed elsewhere to keep America a competitive nation” (“The Brave New World of Health Care”). Not only is the healthcare system destroying itself and the economic position of its players, but it is also affecting quality and efficiency in many other arenas. To be truly effective, reform must take into account not just the roles of the players and the structure of the system, but also how the system affects the economy health of the country as a whole.

References: ‘The Brave New World of Health Care.” Richard D. Gamin, University of Denver, May 1990; “Healthcare Reform: A Closer Look.” Management Accounting, Dec. 1991; “Healthcare Reform Stews in Congressional Pressure Cooker.” Healthcare Financial Management, Jan. 1992; “Wasted Healthcare Dollars.” Consumer Reports, July 1992; “Business and the Future of American Healthcare.” Business Week, June 22, 1992. For other re-sources, call our offices at (617) 576-1231.