As we begin the busiest shopping season of the year, retailers may be in for a big surprise. While holiday shopping usually has people quickly pulling out their plastic, early indications suggest that the great credit card spending party may be coming to an end.

Why are people being more frugal about their credit card purchases? It may be that consumers are so busy paying off their current credit card debt that they don’t have much cash left for additional purchases. The Fortune article notes that the percent of delinquent credit card accounts — accounts that are 30 or more days overdue — has risen from 2.4% in 1994 to about 3.2% in 1995. They also report that the Consumer Credit Counseling Service, a nonprofit organization that helps people in credit trouble, has a caseload of over 800,000 clients “whose consumer-debt loads average $20,000 — no, that’s not a typo — on incomes of just $24,000.”

These and other reasons for the sudden fall in spending can be seen through the lens of the “Limits to Success” archetype (see “Spending & Credit Loop”). The reinforcing loop of this story describes the “spending begets more spending” orientation of our consumer society. As we buy more “stuff,” we increase our standard of living and grow accustomed to the comfort and status of our new spending level. Over time, this increases our desired standard of living, which leads to a desire to buy more things, further increasing our spending (R1).

Optimistic marketers would like to believe that this reinforcing loop is never-ending — that consumers will continually escalate their spending to achieve ever-higher living standards.

But most of us do have limits — in the form of funds available for spending. As our spending increases, our funds available decreases, which requires us to decrease our spending (B2). There are, however, two primary ways to increase the pool of funds available: find ways to increase real income, or simply borrow the money.

Spending & Credit Loop

The favored path in recent years has been to borrow money by using credit cards, which temporarily bypasses the balancing loop through another reinforcing loop of credit line “funds” (R3). But if the real limit, which is the person’s income, has not increased to support the higher spending levels, then at some point spending not only must fall, but it must fall below the long-term sustainable level. This is inevitable, because when we use credit card debt to increase our current consumption, we have done so at the expense of our future consumption power.

Living the “High Life”—with High Debts

So, what’s wrong with borrowing from the future to live better today? If it will all balance out in the long run, why not enjoy certain purchases now rather than wait until tomorrow?

If you pay off your entire balance each month and incur no finance charges, then credit cards can serve as a convenient tool for managing short-term cash flows. But if they are used to expand current spending through increasing amounts of debt, a reinforcing cycle kicks in that will eventually force a drop in spending, as a greater percentage of current spending must go toward paying off the debt.

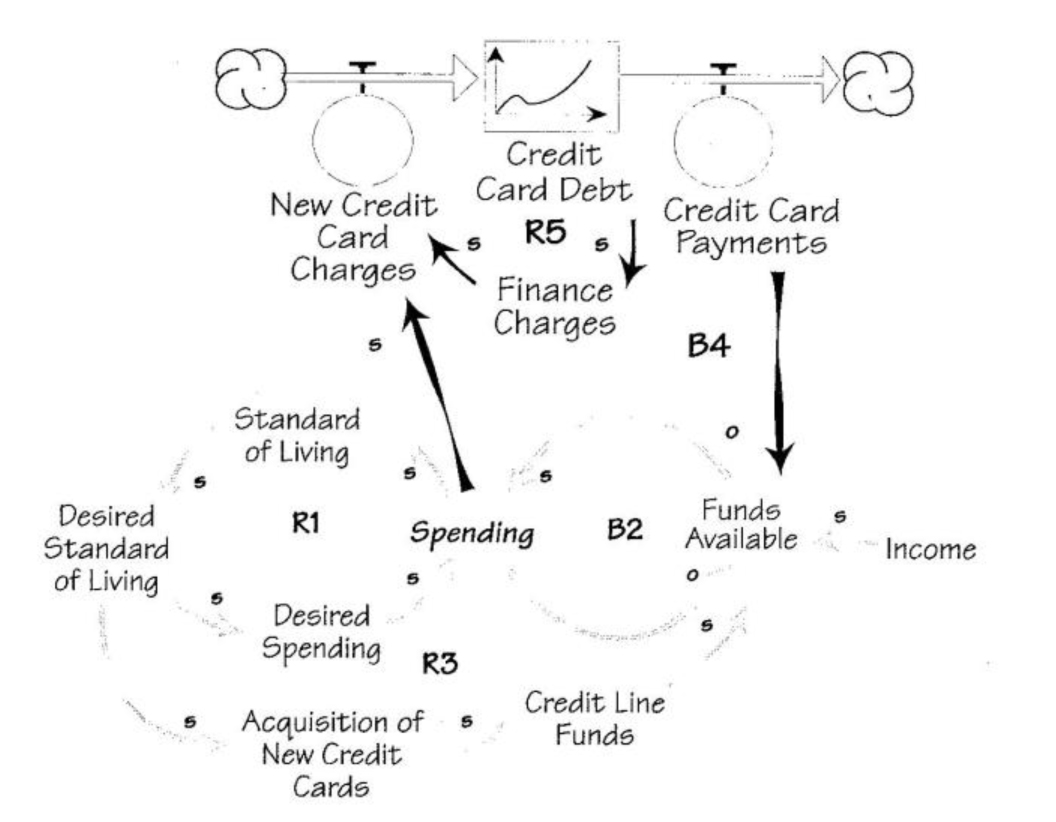

To understand how credit card debt can get so out of control — and how it impacts both current and future spending — we need to look more closely at a stock and flow structure of credit card debt.

Basically, credit cards expand our current spending capability because spending (in the form of credit card charges) is carried in a credit card debt accumulator and does not affect current spending until credit card payments are made (B4 in “Credit Card Debt Structure”). At first glance, it appears that we have simply substituted the original “Funds Available” balancing loop (B2) with the “Credit Card Debt” loop (B4) — a seemingly innocuous change that simply delays payment of purchases. Of course, carrying a balance means that we will have to pay finance charges, so delaying payment comes at some cost. But what is less obvious is how that delay structure distorts our perception of funds available.

Credit Card Debt Structure

When we carry a balance, most credit card companies (with the exception of American Express) only require us to pay off a fraction of the total balance. This allows us to shift our attention away from paying off the total debt toward simply meeting the minimum monthly payments, which makes it look like we have more spending money available than we actually do. In a way, the credit card accumulator helps us “forget” that we made a $1000 purchase, since • our monthly minimum payment has only gone up by $100.

At some point, however, the debt balance gets large enough that the monthly payments themselves are no longer affordable. In addition, the accumulation of finance charges (R5) means that a greater percentage of the monthly payments are going toward paying off interest charges, not toward paying for the actual goods purchased. We can temporarily “fix” this problem by acquiring new credit cards, which prolong the illusion of greater wealth (R3). But sooner or later, the credit card games must end — either we reach our maxi-mum spending limit or begin defaulting on payments. At that point, the debt problem itself must be addressed.

A Debtor Society

Unfortunately, the problem of debt is not isolated to a few overzealous consumers. The U.S. federal debt illustrates the same structure on a much larger scale. Like credit card debt, the federal debt allows the government to decouple current spending from current funds available, and shifts attention to the payments on the debt rather than on the debt itself. But unlike credit card holders, who cannot expand their own credit lines at will, the federal government can simply choose to raise its own credit limit rather than restrain spending (e.g., by selling more Treasury Bills, issuing more government bonds, or raising taxes).

Given both the consumer and national debt crises, it would seem that the United States has become a debtor nation at both the micro- and macro-level. In fact, we seem to have adopted the mentality that being in debt is normal — even desirable. At a national level, it is almost inevitable that our standard of living will fall, as more of our future wealth goes toward paying “finance charges” to the foreign countries that have been giving us their “line of credit.” Just as families are shifting their wealth to the bankers and the retailers, the U.S. as a whole is shifting wealth to Japan, Germany, and other countries.

A Sustainable Future

Of course, there is an obvious solution to both debt crises—stop spending and start saving. Rather than funding current spending with future income, we could instead save current income to be used for future spending. This approach has the added benefit of actually expanding our future spending ability, through the accumulation of interest payments.

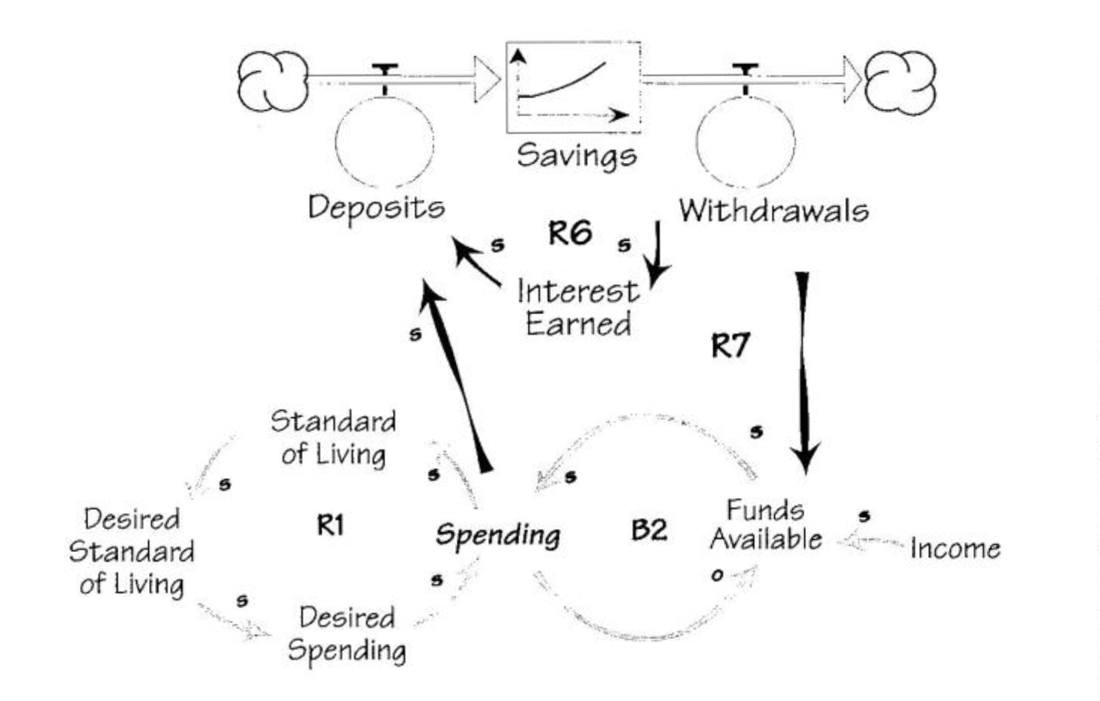

In the “Shift from Debt to Savings” diagram, the credit card debt structure has been replaced with a savings structure. In this situation, some of the current spending is devoted to deposits, which can be withdrawn later to in-crease the funds available at that time (R7). Also, the vicious cycle of ever-increasing finance charges (R5) has been replaced by a virtuous cycle of interest payments (R6). The delay also plays a major role in the dynamics of building savings — once savings reaches a certain level, withdrawals can be made indefinitely without ever touching the principal.

Although the structures are basically the same, the outcome is completely different. While the savings situation provides a sustainable spending approach for the long term, the debt structure does not. Shifting from operating in the debt structure to the savings structure is doubly hard, however, since not only do you have to cut current spending to get out of the debt structure, but you have to cut it even further to begin the savings structure.

Outlining a map of the structure — complete with all the relevant numbers — may help us see more explicitly the full costs and benefits of savings. For example, putting money into savings rather than into credit card purchases results in a double payoff because you avoid finance charges and gain interest payments. One hundred dollars in savings, for example, earns 5% interest and saves 18% in finance charges.

Ultimately, making the shift from the debt structure to the savings structure — both as individuals and as a nation— requires a clear choice. To end the credit game, we need to decide that creating a sustainable future is more important than satisfying current consumption. Such a clear and compelling vision can provide the momentum to see the strategy through — even during the long delay as we pull out of debt and begin the savings structure. Unfortunately, given the short-term focus of our government officials, the prospects of that happening for the U.S. government seem a lot less optimistic than it does for individual consumers.

Shift from Debt to Savings