When beginning an organizational change, we hope it will spread like wildfire, yet we often find ourselves struggling to light the kindling. Organizations change when people in them change — when they think differently about their work and approach it in new ways. What are the factors that can motivate people to accept new ideas about their jobs, fan the flames of people’s commitment, and tip the change initiative toward success?

The answer to this question may lie in turning what we know about the spread of disease inside out. Take the flu, for example. The key to the flu’s spreading is contact. When people who are contagious with the flu come into contact with people who are well, some of the healthy individuals begin to incubate the virus. Depending on many interacting factors, such as the status of their immune system, the virulence of the flu strain, or the amount of sleep they get, some of the incubators go on to exhibit symptoms, become contagious, and spread the disease to others. Other incubators never become sick.

FOUR ATTITUDES TOWARD CHANGE

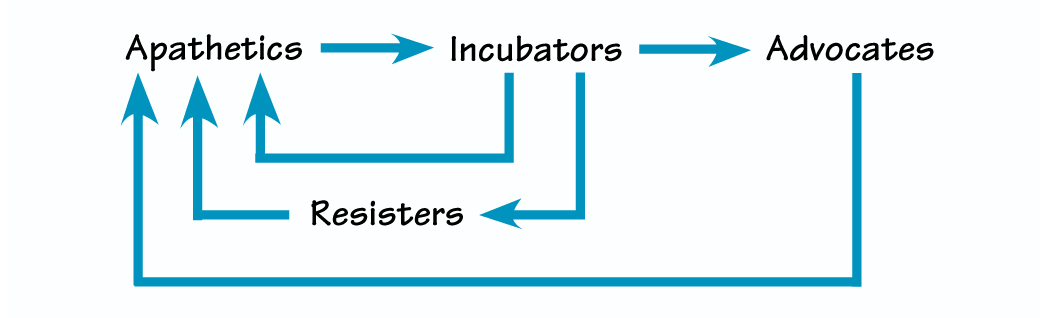

We can apply this pattern of the spread of infection in an entirely different — and more positive — context: organizational change. It is tempting to frame an organizational change in terms of straightforward measurable events, such as when the software is installed or how long the training takes. However, successful change depends first on employees’ accepting and adopting an idea about getting their jobs done. Ideas spread when people with experience in them are “infected” with enthusiasm for them and thus advocate them. When advocates explain their experience with the new way of working to colleagues, some of them begin to mentally test it against their own beliefs and experience; they begin to “incubate” the idea. Others either ignore it or nod in agreement but take no action and remain apathetic.

With time and experience, some of those who are incubating the idea may become advocates for it themselves. Other incubators will lose interest and become apathetic again. Still others will resist the change and work to undermine it. Further, some advocates will retain their contagious enthusiasm for the idea, while others become disillusioned. If enough people become enthusiastic about the idea, we have a positive epidemic of change (see “Four Attitudes Toward Change”). (For an example of applying these ideas to a change effort, see “The ‘Infectious’ Spread of Change at Nortel Networks” by Carol Lorenz and Andrea Shapiro in The Systems Thinker, Vol. 11 No. 6.)

Motivating and Supporting Change

To apply the dynamics of the spread of epidemics to organizational change, we need to identify the factors that motivate and support change, so that acceptance of new ideas becomes contagious and spreads throughout the organization. By supporting conditions and behaviors analogous to those that produce the spread of disease, we can catalyze healthy epidemics of, enthusiasm for, and commitment to an organizational change.

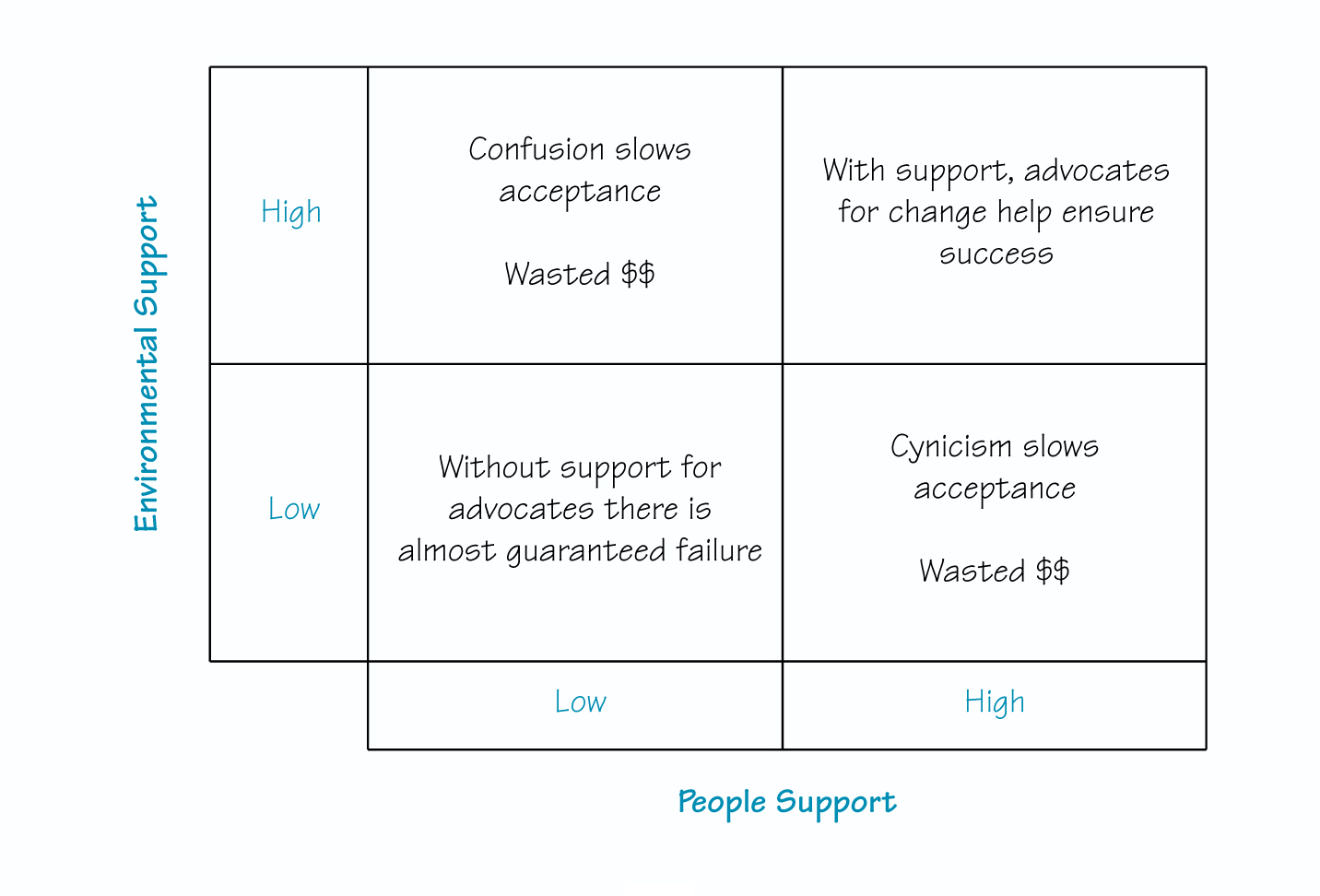

Leaders play a key role in enabling this kind of change by providing people support and environmental support. People support includes explaining what to expect from the change, listening to concerns, and fostering contacts between advocates and others. Environmental support, which helps create the atmosphere for change, includes making the business case clear to all stakeholders, putting necessary infrastructure in place, and rewarding those who support the change (see “People and Environmental Support Interact” on page 3).

Lessons from public health teach us that whether or not a disease spreads depends not only on the virulence of a disease, but also on where it is happening and to whom. For example, by the time of New World exploration, measles and smallpox were still serious health threats in Europe but were no longer true plagues. However, those same diseases wiped out entire Native American villages, because measles and smallpox were new to those populations; they did not have the immunity that Europeans had developed over generations of living with the diseases. Likewise, cholera spreads quickly in areas without clean water supplies, but it is virtually unknown where people have ready access to clean water.

Analogously, the speed with which an idea or change initiative spreads in an organization depends not only on the innate value of the idea but on environmental factors, such as the amount and quality of contact its advocates have with people who are apathetic to it, the firm’s system of rewards and recognition, the type of leadership practiced, and the investment in infrastructures that support the change. A good idea could spread like wildfire in one environment but have no effect in another.

Leveraging Resistance

Just as people can develop resistance to a disease — sometimes even complete immunity to it — so too in organizations, people may push against or resist a change. Resistance to change typically manifests in several ways. People may express constructive concerns that a change is incomplete, too much of a cultural leap for the organization, misunderstood, inappropriate, or ill-timed. Resistance that stems from genuine concern can serve as an early warning system that helps the organization strengthen the initiative and avoid failure; it can spark exploration for better methods of implementation or improvement of the change effort itself. When constructive concerns are aired and acted on suitably, they become a source of innovation and enhance the likelihood of success.

On the other hand, if leaders and others in the organization interpret legitimate caution as a challenge to the effort or to management’s authority, then they lose an opportunity to learn and improve. Worse, if leaders try to push the project in the face of resistance or try to punish resisters for their stance, resisters will likely become more covert in their opposition, increasing their potential to undermine the effort.

One marketing director at a telecommunications company uses resistance to optimize her company’s change efforts. She sees it as her responsibility to intentionally question every organizational change that touches her department. Occasionally, this tactic backfires, and other managers label her a troublemaker. But her experience has shown that when she is honest, consistent, and constructive with her questions, the result is usually positive. Her inquiries often reveal problems with the change initiative or its implementation, and her feedback saves the company time and money and yields a stronger initiative — generally with a positive effect on her department and budget.

A more dangerous source of resistance stems from too much exposure in an organization to change initiatives that were touted as important innovations, never fully implemented, and ended up as mere slogans on T-shirts and coffee mugs. This kind of resistance can damage any future change initiatives — no matter how much they’re needed because employees now associate them with meaningless hype. Similarly, when changes are misrepresented, for example, with false claims of benefits to employees, an atmosphere of cynicism develops. Leaders can minimize this type of response by wisely selecting which organizational changes to undertake, presenting them honestly, and being prepared to fully sponsor them through to successful implementation (see “A Failed Change Effort” on page 4).

A third form of resistance comes from people’s fears that the change will result in the loss of their jobs, authority, influence, or bonuses. These possible outcomes lead them to perceive that the future is outside their control, a perception that can foment rumors and unrest among employees. The best ways to approach this source of resistance is to be candid with employees and share valid information. For instance, if a merger or reengineering effort will result in layoffs, spell out the reasons for the downsizing and the numbers of people affected as soon and as clearly as you can; otherwise, the rumor mill will portray the situation as worse than it actually is. Knowing the real picture and believing in its accuracy gives people a sense of control and helps alleviate fear and resistance.

PEOPLE AND ENVIRONMENTAL SUPPORT INTERACT

Supporting Advocates

Most changes fail due to apathy; they are simply ignored to death. Empowering the people targeted for the change and cultivating the expertise, experience, and enthusiasm of the advocates among them can turn this apathy into energy.

A FAILED CHANGE EFFORT

Medical Machines had gained significant market share in automated hospital diagnostic tools. The company sought to further develop its customer base by developing smaller, more portable, and more automated equipment, using wireless transmission to increase their capability. With the new devices, Medical Machines ventured into areas in which they had little experience. The sales force lacked familiarity with these products, and the sales and engineering departments didn’t communicate well.

As a result, Medical Machines began having problems meeting promises made to customers. Managers felt that a knowledge management (KM) system would help engineers and sales support personnel communicate about new projects and changes to existing ones. Top management assigned the implementation task to the vice president of information technology. His team immediately began the process of adapting a commercially available system.

Within a year, the company made the KM system available to both engineering and sales, complete with logo mugs and a huge fanfare. However, the launch team didn’t do anything to foster knowledge sharing. The organization rewarded the team for implementing the KM software, but didn’t put into place any rewards for actually using it. Consequently, few employees saw its value to themselves or to the firm. In fact, many resisted the change because they felt that, by sharing knowledge, they might be giving away their edge to bonuses and promotion. The KM system because a little-used and expensive piece of software.

We can see what Medical Machines could have done better. To begin with, they mistook the technical content of the change for the change itself. They saw it as a technology implementation without recognizing the cultural changes that were needed to make it successful. They did not identify the advocates of knowledge sharing, so they were hardly in a position to support them in any way. No one took the time and effort to listen to the resisters’ concerns, which could have been addressed by making the business case clear and by initiating incentives for sharing knowledge. In short, Medical Machines did not create the environment for change, where the employees who had knowledge to share felt safe sharing it and making the KM system successful.

No matter how important a new way of working may be or how enthusiastic its advocates are, without support from the top, the idea is unlikely to spread throughout the organization. When key leaders create

Most changes fail due to apathy; they are simply ignored to death.

a solid foundation for an initiative, with commensurate infrastructure, rewards, and recognition, and lead by example, people are much more likely to listen to the change advocates and take their experience seriously. Leadership’s role is to support, not to force compliance. A “do it or else” threat is not an endorsement of a change and does little to engender the kind of commitment that spreads under its own momentum.

Traditional linear thinking leads us to believe that large efforts lead to large effects. Experience with implementing change initiatives demonstrates that large efforts promoting a change can have frustratingly small effects. For example, a huge one-size-fits-all training course can have little — or even negative — impact despite the investment in energy and resources. Small, ongoing measures, such as initiating informal networks to support advocates, are proving to have much more significant and lasting effects in the long run.

The drivers of change are not static, and an organization may be faced with implementing several changes in a short time. Maintaining support for each change helps create mechanisms that can be applied again and again. Eventually this process can lead to a capability in change management; that is, the organization acquires the nimbleness to quickly implement new policies and actions that it needs to succeed.

Creating Critical Mass

Understanding and appreciating each individual’s change style can help leaders build a critical mass of support for their change initiative. According to Chris Musselwhite, an adult learning expert, people have one of three change styles that influence their attitudes toward change in general and toward a specific organizational initiative: originator, pragmatist, and conserver.

Originators are motivated by radical change that challenges the status quo and existing structure. They look for new and different ideas with potential for dramatic results. Pragmatists want to see problems solved in practical ways that reflect current demands. They focus on results and seek functional change. Conservers — if they have to make a change at all prefer incremental change, such as putting existing resources to better use. They seek to preserve the existing structure whenever possible.

The challenge to implementing any change idea is optimizing the strengths that each group brings to the table while minimizing their weaknesses so that they can work effectively together. The early advocates of a change idea are typically originators; they can see the broad possibilities of the change. But they may overlook the disruption that change can trigger and the harm to the existing structure that is serving the company well in many ways. Also, the broad terms in which they paint the possibilities do not appeal to the pragmatists, who need to ground the change in practical, no-nonsense applications that address current challenges. Conservers usually hold off adopting a change until they are fully convinced of its functionality.

One way to help all three groups maintain enthusiasm for a change is to create early wins, an idea outlined by John Kotter in his book Leading Change (Harvard Business School Press, 1996). Because a significant change takes time to put into operation, establishing an early win, such as a successful pilot program, can bring credibility to the effort while full implementation is in progress. Early wins that are explicitly measured, well rewarded, and broadly recognized help pragmatists see the value of the change initiative. Once a change does speak to a broad cross-section of originators and pragmatists, it will have gained a critical mass and, more importantly, cultivated the right mix of innovators and pragmatists who can influence the conservers and thus tip the change toward success.

Developing Advocate Skills

There is no substitute for expertise, experience, and enthusiasm when advocating for a change. People who make the best advocates are those who will be affected by the effort, who have experience with it, and who are respected by their peers for what they contribute to the product or service that the company produces. Experience with the change is key to influencing others’ perspectives because it allows advocates to explain the value

of the initiative in very concrete terms and to tell “stories” about the change that people can identify with. No matter how much experience and enthusiasm advocates have for a new way of operating and no matter how much they are respected for their expertise, to be truly effective, they must also be skilled at knowing how to spread the word. To this end, they need three important capabilities:

Experience with the change is key to influencing others’ perspectives.

- Skilled conversation — to help advocates listen to the concerns of resisters and raise important issues to leaders and peers,

- Fluency with the law of the few — to give them insight into whom to contact and encourage to join the advocate pool, and

- Sensitivity to change styles — to allow them to tune their language to the style of the other person.

These skills are vital to creating the critical mass necessary to tip the organization toward a significant change.

Skilled Conversation. Skilled conversation involves creating a balance between inquiry and advocacy, listening well, and holding multiple perspectives to get a more complete picture of what the change entails. In The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook (Currency/Doubleday, 1994), Richard Ross and Charlotte Roberts describe the value of both advocacy and inquiry. To them, advocacy involves expressing a certain position convincingly, forcefully, and clearly; it requires presenting your own assumptions, distinguishing between data and opinion, and articulating the logic and reasoning behind your conclusions. In contrast, inquiry means seeking to understand another’s position by listening well and reflecting back what you heard, as well as seeking to understand the data and reasoning behind their conclusions and avoiding imposing your own interpretation on them.

Balancing advocacy and inquiry is especially important when dealing with apathy or resistance. Overt resisters often have legitimate concerns about the change or about management’s true commitment to it, and inquiry can be useful to understand those concerns and the assumptions behind them. On the other hand, an apathetic person is more likely to incubate an idea if a promoter uses advocacy to clearly state the case for change with all the underlying assumptions and reasoning.

Fluency with the Law of the Few. Knowing which people in the organization to get on board for a change is another key skill for spreading an idea quickly. In his book The Tipping Point (Little Brown & Company, 2000), Malcolm Gladwell discusses the “law of the few” in his description of factors affecting social change. He says that three different types of people — mavens, connectors, and sales people — can make the difference between an idea’s spreading or not. Mavens are the ones who always seem to know the important answers; they are the gurus to whom others consistently turn for advice and recommendations. Connectors are those excellent networkers who just seem to know everyone and can connect people from different groups who would otherwise remain segregated. Sales people have the ability to persuade, a skill they call upon when they really believe in something. According to Gladwell, it only takes a few people with these skills to make a huge difference in how, or if, an idea spreads — which is why it is important to get them into the advocate pool early in the change effort. Conversely, if these people are among the resisters, they can be deadly to the change initiative.

NEXT STEPS

If you are implementing a change, here are some actions you can take to prevent it from being “ignored to death”:

-

- Ask yourself who the effective advocates are for the change. How might you support them in spreading their enthusiasm for the new idea?

- Identify those who might resist the idea. What can you do to get resisters’ concerns out in the open?

- Once you have a plan in place to support the advocates and communicate with the resisters, find ways to cross the communication gulf between early advocates, who are typically originators, and conservers. What “early wins” can you create to help everyone see the value of the change initiative?

Sensitivity to Change Styles. Because early advocates tend to be originators, they need to be aware of their own and other people’s styles, whether they are originators, pragmatists, or conservers. To conquer apathy, they must meet each person where he or she is by seeking to understand the values of the pragmatists and conservers and using language and examples that speak to them. Otherwise, it may be difficult to convince others to even incubate the new idea.

Moving Forward

It is tempting to believe that we can make changes that are vital to our organizations by simply modifying organizational charts, improving processes, or adding new technologies. Although organizational change might include new structures, processes, or technology, it involves more than any of these alone or in combination. It is fundamentally a change in people. Organizations change when people entertain creative ideas and approaches about how to do their work.

Ideas can be contagious. When ideas offer new and better ways of working, we want to make them contagious. We can do this by turning the lessons from public health inside out. By leveraging the power of advocates of change, with proper support from management, we can make change initiatives both contagious and sustainable. Doing so can help us create a capacity for change that is a potent lever for future growth.