I recently worked with a group in a high-tech computer company that once had a very alive sense of community. The people felt more connected, more efficient, and there was a high sense of trust within the group. Productivity and learning were phenomenal.

Results were so good, in fact, that management infused the group with millions of dollars to upgrade its working environment and add more staff. But a year later, this group no longer felt like a community, and everyone was afraid to say so. Management pretended that everything was as it had been, and anyone who offered evidence to the contrary was considered a traitor.

In examining the history of this group’s process, it was easy to see that no one had expended effort to keep alive the one resource that had made the group so successful: its spirit of community. Everyone just assumed that if management financed an expansion of the project, the sense of community would automatically continue.

A collective spirit of community, such as the one experienced by the original group, is highly prized. Yet more often than not, actions intended to preserve this spirit drive it out instead. In the case of the computer firm, the development of community was largely ignored to death.

What Is a Community?

A mature community is characterized by an inclusiveness of diverse people and information, semipermeable boundaries, and a systems-oriented paradigm. In such a workplace, there is an openness to creativity and innovation. The organization becomes, in effect, a group of leaders who embody a profound sense of mutual respect and have the ability to fight gracefully while transcending differences. The benefits of corporate community include a profound sense of trust and collaboration, which leads to a coherent organizational vision.

A collective spirit of community, such as the one experienced by the original group, is highly prized. Yet more often than not, actions intended to preserve this spirit drive it out instead.

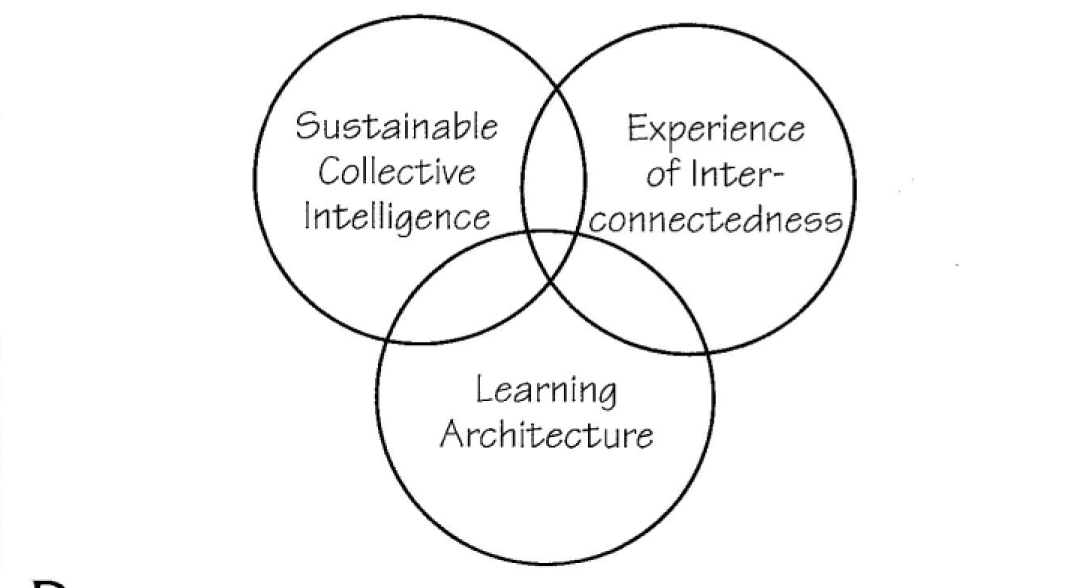

How can an organization consciously and strategically develop competence in community building? It must first make the commitment to learn and grow as a community throughout its life cycle. Developing such a competence depends on a balanced growth of three interrelated elements: the experience of interconnectedness; sustainable collective intelligence; and learning architecture (see “Core Competence in Community Building”). Sustaining community over the long term also requires an organization to go through several stages of growth, each with its own set of developmental challenges. By anticipating these challenges, we can prepare to respond in ways that optimize growth and change while minimizing chaos.

Interconnectedness

Almost anyone who has survived a significant crisis in a group knows the spirit of community. Starting a new organization, enduring a tragedy such as the death of a colleague or friend, or experiencing a natural disaster can all lead to a spirit of interconnectedness in a group. In these cases, community arises as the result of a group’s need for survival.

In business, this survival goal can be the starting point for developing a culture that deliberately fosters community throughout the course of the work-day. Rather than depending on haphazard events such as crises, a team can actively nurture its capability to create experiences of interconnectedness through authentic communication. Paradoxically, it does this by acknowledging differences.

The typical organization is essentially what M. Scott Peck, author of The Different Drum: Community Making and Peace, calls a “pseudocommunity,” an organization unwilling or unable to acknowledge its differences. However, a group can be taught the discipline of learning to acknowledge and transcend these differences. If members are willing to learn how to face reality together, they can develop authentic and vulnerable communication. Through such a process, the organization can become aware of its barriers to true community.

When teams and organizations manage to experience interconnectedness — with its benefits of authentic communication, safety, and intimacy — they are often so enthusiastic about these benefits that they try to stay in this state continually. But after a while they notice that their attempts actually create less sense of community. The lesson here is that the spirit of interconnectedness in a community is not a permanent state. It ebbs and flows with the community’s life cycle — and when it is not present, it may be a signal that one or both of the other two aspects of core competence require attention.

Sustainable Collective Intelligence

A second aspect of developing a community has do with enhancing the collective intelligence of a group. If a group cannot convert collective intelligence into organizational action, it can easily become a support group rather than a high-performing learning community. Creating such collective intelligence means actively nurturing the sense of community while simultaneously acting and making decisions that can improve the group’s thinking skills.

One method for developing collective intelligence is the dialogue process introduced by physicist David Bohm. Dialogue focuses on creating shared meaning by surfacing and examining assumptions within a group. It emphasizes the importance of rational and cognitive group learning. As David Bohm described it, “[the word ‘dialogue’] suggests a stream of meaning flowing among and through us and between us. This will make possible a flow of meaning in the whole group, out of which will come some new understanding.”

In business, this survival goal can be the starting point for developing a culture that deliberately fosters community throughout the course of the workday.

Dialogue is very effective for exploring fundamental assumptions underlying group thought, but because of its focus on cognition, it limits the range of emotion within a group. An alternative is to incorporate Bohm’s cognitive emphasis with Peck’s focus on authentic feeling states and stages of community building (see “Community Building: A Four-Stage Model”). Combining dialogue and community building can allow a group to shift rapidly between “head” and “heart,” allowing for a collective intelligence that can be sustained more easily over time.

Learning Architecture

Collective rhea tea and action ate required in order for groups to change the complex architecture that either supports or inhibits community. The learning architecture of community consists primarily of the systems and structures that sustain memory and learning in the organization over time. The compensation system, career development process, style of leadership, methods for distribution of power and governance, and physical structure of the site all affect a group’s ability to experience itself as an authentic community.

Understanding how the organization’s learning architecture enhances or blocks community is critical to realizing the trust, joy, and flexibility of community. No amount of attention to team spirit or learning will be productive if the structures of the organization cannot or will not be changed to support community. More often than not, an organization that is having difficulty sustaining a sense of community is operating with systems that create fragmentation or disempowerment.

Systems thinking’s emphasis on structural diagramming and identifying high-leverage interventions can help in creating structures that support community. This work is critical, because even when the organization’s leadership politically backs the enhancement of community, if the organizational structures are prohibitive, they can inadvertently destroy hope.

Sustaining Community

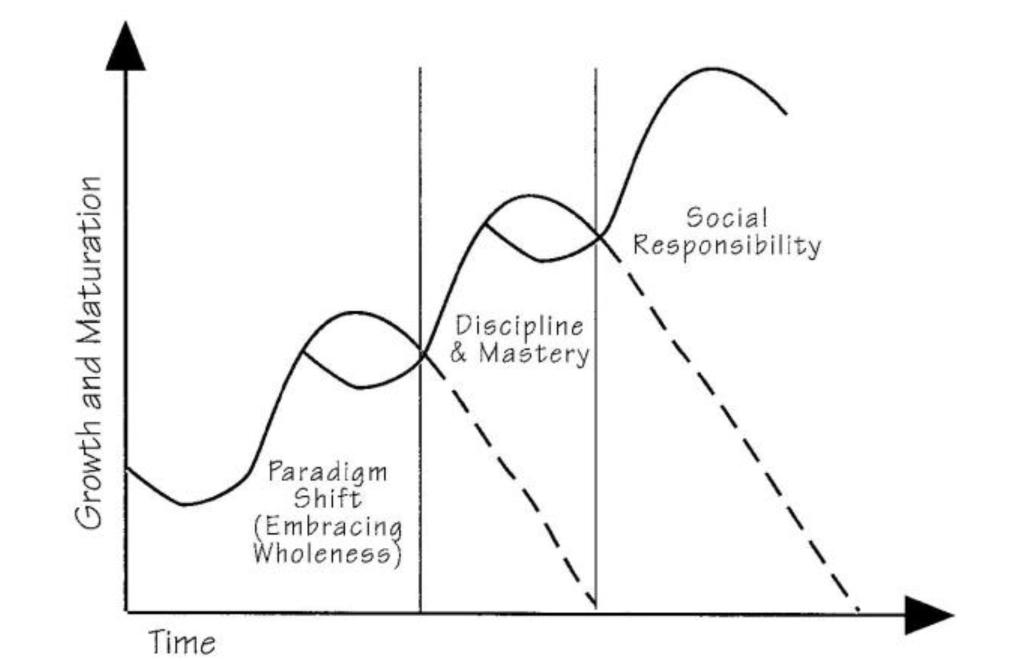

With the actualization of the three aspects of core competence — interconnectedness, sustainable collective intelligence, and learning architecture — an organization takes its first steps to becoming a community. Developing a core competence in these three aspects, however, is just the starting point for long-term growth. Like a child that grows to maturity, all three elements must grow in harmony and balance for long-term health and vitality. And just as humans go through infancy, adolescence, and adulthood, communities go through necessary growth stages and transitions as they mature (see “Community: Stages of Maturation”).

Core Competence in Community Building

Community Building: A Four-Stage Model

Building or experiencing community can be described as a four stage process:

Pseudo-community. During this stage the group pretends that it already is a community and that differences do not exist. The decision-making process and the nature of relationships go unchallenged, and “politically correct” or polite behavior dominates.

Chaos. The sense of apparent control and order is disrupted when differences emerge. The group tries to obliterate these individual differences by polarizing topics, looking for winners and losers, or changing each other. Replication and duplication of what has worked in the past is mandated, and decisions are made via competition, political power, and authoritarian control.

Emptiness. Having failed to control or organize in way into community, the group steps into true chaos; uncertainty and ambiguity replace control. The group begins the work of self-examination, giving up personal obstacles, barriers, and agendas. It is the beginning nitrite listening, where the group’s decision-making process becomes collaborative.

Community. Having emptied itself of its previous mental models, the group is available for authentic communication. Authentic connection is achieved by acknowledging differences. In this safe place, creativity emerges. The group as a whole makes decisions co-creatively, learns as an entity, and innovates as a whole.

By definition, growth necessitates a certain amount of pain. If the organizational community avoids the pain of growth, it stops the learning process. But if it consciously embraces the three developmental learning challenges described below, an organization will find opportunities to grow spiritually, psychologically, and competitively.

Paradigm Shift—Embracing Wholeness

The first developmental stage in sustaining community is to wrestle with the assumptions of our prevailing mechanistic paradigm. Businesses cannot sustain themselves as communities or learning organizations unless they become capable of embracing a paradigm of wholeness.

Although a community-based perspective can be temporarily grafted onto an organizational world view that seeks answers in linear causality, such a transplant will not “take.” Community responds best to cyclical, nonlinear processes. Organizations destroy community when they treat it like a mechanical process made up of linear cause-and-effect relationships.

In his groundbreaking work on paradigms, Thomas Kuhn explained that a group holding onto old ideas and values will often choose to die conserving them rather than risk the learning required for change. The only remedy to this situation that Kuhn offered was to wait for people to die off over time, thus paving the way for a new paradigm to emerge. Unlike the ill-fated groups that Kuhn described, businesses can use the technology of community building to make the transition between paradigms consciously.

Community: Stages of Maturation

A typical organization that has been successful and profitable for extended periods of time can fall out of touch with the “real world,” and the company’s culture can become unquestioned, much like a paradigm. When this happens, the leadership of the organization needs to pierce this unreality by challenging mental models and fostering an environment of trust where a new world view can actually take hold.

However, since our traditional organizations create and legitimize paradigms, acts of individual leadership arc usually ineffective in changing them. The community-building process must therefore challenge and transform the collective world view. At this stage in the community’s life, the principle leverage point for growth resides in creating effective ways for the collective intelligence of the group to create new individual and organizational models of reality.

Discipline and Mastery

No organization can have a positive learning environment or feel like a “family” at all times. The evolution of a living community includes turbulent times that occur as we encounter one another’s and the organization’s under-developed areas. A learning organization that embraces community as a core competence thus requires day-in and day-out practice of what I call “discipline and mastery,” so that the community and the individuals within it move toward optimum competency and aligned organizational purpose.

M. Scott Peck and Peter Senge both see learning as a lifelong program of study — what they call a “discipline.” In The Fifth Discipline, Peter Senge explained, “By ‘discipline’ I do not mean ‘enforced order’ or ‘means of punishment’ but a body of theory and technique that must be put into practice. A discipline is a developmental path for acquiring certain skills or competencies. As with any discipline…anyone can develop proficiency through practice.”

I believe that developing a core competence in community building requires four main leadership skills (originally described by Peck as a system of discipline):

- Delay gratification. Foster the ability to hold tension between the vision and the current reality, and be able to see the actual reality of a situation without jumping to problem solving. Embrace larger and more systemic views, avoiding the simplicity of linear causes and obvious solutions.

- Dedication to the truth. Boldly acknowledge what learning the organization needs to pursue. Seek to embrace unpleasant truths. Acknowledge the gap between intended and actual outcomes in order to remove the barriers to learning.

- Assume responsibility. Practice willingness to act as a fearless learner, to move beyond blame or judgment of oneself or others for the purpose of learning. Take responsibility for change.

- Balance learning. Discipline must be subject to a system of checks and balances or it can easily lead to burn-out, excessive work, or a “task master” mentality. To truly benefit from learning, we need to provide periods of “slack time” for integration, relaxation, and play. Without balance, learning is less effective—and no amount of discipline can substitute for compassion and care.

Social Responsibility

Once a learning organization has embraced a paradigm of wholeness and established itself as a sustainable learning community, it will find itself called to address its responsibility to the larger society. This final developmental stage is really just a starting place for another level of growth.

An organization at this level of development will discover that its impediments to community are intrinsically tied to the limitations and systems that govern the larger society. For example, in the West, interlocking systems of oppression (such as racism, sexism, and classism) will inevitably emerge as obstacles to sustaining the community. These larger social issues will have to be addressed within the organizational goals of the company. Many organizations are surprised by the level of tension and struggle that is intrinsic to a mature community. They expect that mature communities are tranquil. But community is paradoxical: the more spiritually mature it becomes, the deeper the concerns it struggles with.

No amount of attention to team spirit or learning will be productive if the structures of the organization cannot or will not be changed to support community.

The fully mature community will encounter turbulent times, because once individuals and organizations reach this level of social awareness, the organization will need to reclarify its fundamental vision, values, and purpose. It will require this new clarity to balance its vision against its need to act on social issues. Because of past experiences of interconnectedness, a community will undoubtedly recognize that its survival is linked to that of the larger society. It can then develop a social vision that complements the organization’s profit-centered vision.

The Journey Toward Authenticity

In an effort to build sustainable communities, managers sometimes try to apply traditional management methods, much to the community’s detriment. There is a difference, however, between the responsible measurement of results and measurement that kills incentive.

Those managers who are preoccupied with measurement over results tend to ask: How is community defined? How can we measure it? What results has it produced so far? This kind of leadership leaves organizations starving for authentic connection, since individuals who are preoccupied with evaluation often do not have energy for the work of building community.

A business seeking to become a learning organization by developing a core competence in community is embarking upon a complex and rewarding journey. This journey includes making a shift from hiding complex problems to not only confronting them, but actually using them to gain competitive advantage.

Embracing this journey provides a way for a business locked into an old paradigm, or stuck in the stage of pseudo-community, to transform itself into a more authentic community. Once learning and authentic connection become integrated, the organization can then release the talents and gifts of the community members in a way that produces results far beyond the capability of any one individual.

Kazimierz Gozdz is the editor of Community Building in Business: Renewing Spirit and Learning in Business (Sterling and Stone: expected May. 1995). He is a research affiliate at the MR Organizational Learning Center and an organizational consultant specializing in transforming businesses into learning communities. Editorial support for this article was provided by Colleen Lannon-Kim.