Like many organizations today, Cabletelco Corporation*, a major developer and operator of broadband cable networks, serves its customers via call centers — physical and virtual organizations of customer service representatives (CSRs) whose responsibilities extend from arranging for services to resolving billing issues to troubleshooting technical problems. The CSRs provide all these services to customers over the telephone.

In 2002, as Cabletelco’s product offerings and customer base grew, the Call Center for the Northeast Region faced the ever-increasing challenge of serving diverse customers with multiple products and high levels of technical complexity. To address these obstacles and opportunities, a team from within the Call Center organization was formed. This cross-functional group collaborated on solutions for matching the flow of work, the design of jobs, and various processes to the way the business needed to operate in order to be successful. The group included the vice president of Customer Care. It was empowered to make decisions related to the customer service organization as well as to make recommendations to the Northeast Region senior leadership team on matters that involved additional budget expenditures or staffing.

One aspect of the challenge involved the Call Center supervisors, who continually struggled to eek out time to complete performance management and employee development functions. Supervisors found themselves “playing out of position” for several key reasons:

- They were increasingly called on to train workers on matters such as changes in call-handling policies, new marketing campaigns, and the effects of computer technology changes on customer interactions.

- They were responsible for more and more administrative tasks, including updating databases, adjusting payroll, monitoring adherence to schedules, and filing various reports. The most fundamental reason that supervisors failed to accomplish some important tasks was that they spent much of their time fielding complex calls that CSRs were not equipped to handle. It was common for a supervisor to report for her shift, step into her office, and face a stack of “escalated” calls that were waiting for her. All too frequently, managers spent their entire shifts resolving such issues.

Why were so many calls passed along to supervisors?

- First, the large volume of changes in the business, including the institution of multiple billing systems, had made the customer service representative’s job increasingly difficult and complex.

- Second, consistently high CSR turnover rates reduced service levels, service quality, customer satisfaction, and job satisfaction. Thirty-five percent of CSRs and 120 percent of service representatives at a key outsourcer (used to handle the ever-increasing call volume) left each year.

- In turn, the level of experience among the CSRs had fallen. Since 1999, the average tenure had declined from 4.5 years to just one year.

Although there were certainly instances when it was appropriate for a supervisor to handle a call, such as when a customer asked to speak directly to a supervisor or wanted to complain about poor service, the team studying the problem felt that many of the escalated calls could be avoided by increasing the CSRs’ ability to handle them themselves. To do so, they would need to develop competencies in:

- Clearly explaining company policies to customers

- Using information technology to locate answers to customer questions, such as which marketing campaign was currently in effect

- Diffusing irate customers

But with the volume of work, the rising complexity of the CSRs’ job, and the low experience base of the workforce, it was evident that change wasn’t going to happen overnight.

Clearly something had to be done.

A Systems Approach

Fortunately, a good proportion of the team had experience with systems thinking from a previous workshop I had given on the essentials. The others were given a tutorial and were brought up-to-speed quickly. The group as a whole then began to tackle the problem of escalated calls from a systemic perspective.

They determined that the quick-fix solution to dealing with escalated calls while freeing supervisors to perform their more traditional duties would be to create a new “development specialist” role to handle complex calls. (Another would have been to add more supervisors, but the company had a firm supervisor-to-CSR ratio that could not be changed for cost-containment reasons). The more fundamental solution would be to further develop the CSRs’ competencies to handle calls themselves.

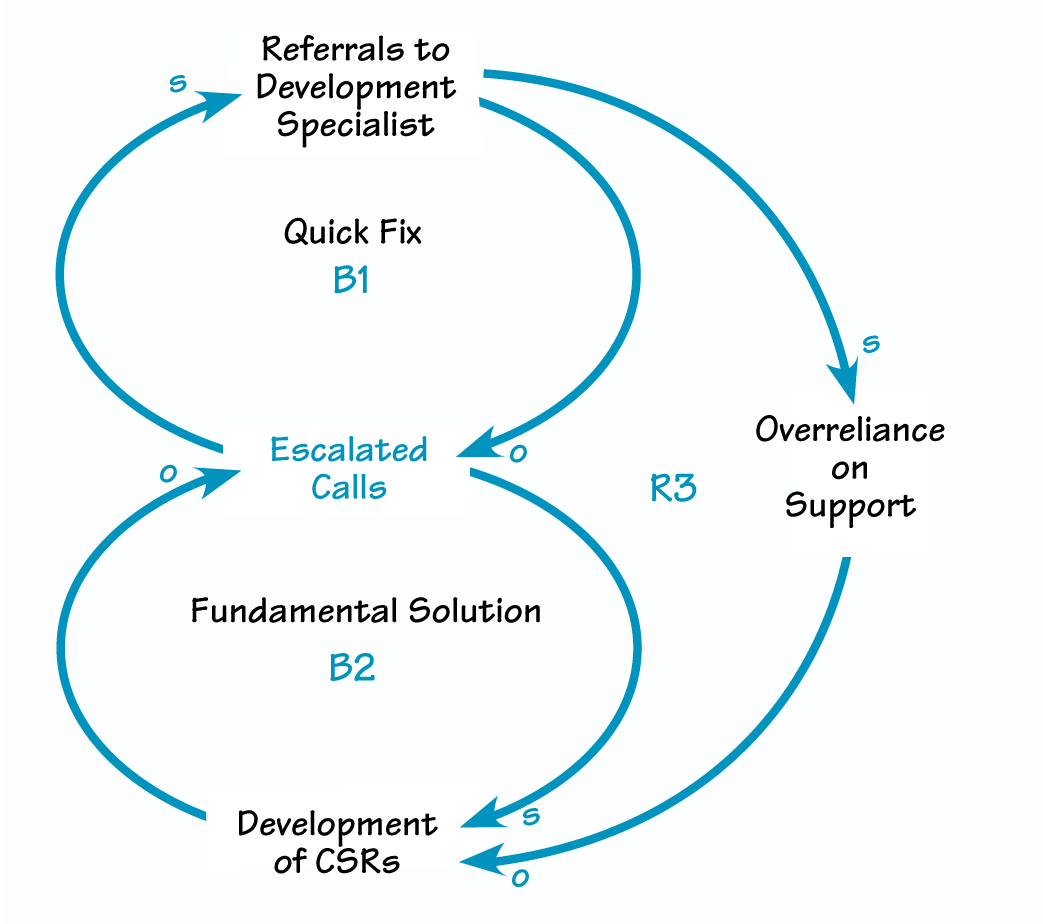

The team recognized that if the company only took the step of instituting the development specialist role to handle escalated calls, the calls would get handled, but the CSRs wouldn’t gain additional skills nor would their job satisfaction increase (a key factor in reducing the high turnover rate). This quick fix would effectively undermine the development of the CSRs by creating an over-reliance on, or “addiction” to, the specialists. In effect, it would simply shift the problem from the supervisor’s desk to the development specialist’s desk without ever addressing the underlying causes (see “Shifting the Burden to Development Specialists”).

SHIFTING THE BURDEN TO DEVELOPMENT SPECIALISTS

In systems thinking terms, this is a classic example of the “Shifting the Burden” archetype, in which a short-term fix actually undermines the organization’s ability to take action at a more fundamental level. Piece by piece and variable by variable, the team built the systems loops and connected them. The visual model became an easy way to understand the dynamics and to present the analysis to top management and others.

From talking through the causal loop diagram, it became clear that the key was to make sure that any solution for meeting the Call Center’s immediate needs would also support its long-term viability. To fulfill both of these goals, the group recommended the hiring of development specialists to help handle the influx of complex calls. At the same time, to mitigate over-reliance on the development specialists while ensuring the success of the role, the team proposed that:

- The development specialists help CSRs build the capacity to handle complex calls themselves.

- Supervisors take advantage of the time freed up from handling escalated calls to focus on performance management and CSR development.

- Supervisors continue to take some escalated calls in order to have direct insight into customer issues and CSR work challenges.

One way that the development specialists would help CSRs develop their skills was through a technique known as “side-jacking.” Rather than hand off a call to a development specialist and be done with it, a CSR would stay on line as the specialist handled the call to witness, learn, and develop the means to resolve the problem. The development specialist would also debrief the call with the CSR to build understanding and competency.

The expected impact of this approach was:

- CSRs would develop their ability to handle complex calls.

- The workforce as a whole would be more capable, experienced, and able to handle calls efficiently.

- Customer service/customer satisfaction would increase.

- Employee satisfaction would increase, and turnover might decrease.

- Fundamentally, CSRs would be better equipped to solve customer problems — effectively creating a “smarter” workforce.

Sharing the Burden

By taking a systems viewpoint on the situation and thoroughly describing the dynamics at play, the team was able to get management to agree to add the development specialist role to the workforce at a time when headcount was being strictly managed. The logic of the approach and the completeness of thinking represented in the portrayal of the “Shifting the Burden” archetype gave the team confidence in their recommended strategies, allowed them to get support from leadership to proceed, and provided a basis to clearly communicate their plans to the workforce.

One year later, the development specialist role has proven to be a valuable addition to the organization. The CSRs have improved their skills. With side-jacking, they walk through difficult calls with a development specialist and observe how the problem is handled. The next time a similar call comes in, they are inclined to first attempt to handle it themselves before passing it along. Most important, the number of escalated calls has been reduced, and more customers get taken care of the first time they call.

With the addition of advanced technology, development specialists will be able to monitor the work of each CSR four times a month and see how they are solving problems and creating work orders. This data will serve as the basis for further development conversations. Fittingly, perhaps, development specialists have started to move into supervisory roles as the organization has continued to grow, while CSRs have been promoted to fill the development specialist role. One indicator of success is that turnover among CSRs has declined by 6 percent annually.

Many of the improvements the team came up with to improve the way the business operated have taken root. Systems thinking allowed them to pull their disparate thought processes together, create a coherent solution, and sell and implement their proposal.

Jack Regan is principal of Metis Consulting Group, Inc., a management consulting and training firm whose mission is to initiate and build workplace communities where individuals and organizations realize the results that most matter to them. Over the past 16 years, Jack has focused on the design, facilitation, and management of organizational change. He has worked with leaders and teams in a variety of industries and communities on strategic thinking, planning, and implementation, and has used his consultation expertise to enable clients to produce both demonstrable business results and relevant cultural renewal.