When Monsanto and American Home Products dissolved their intended merger last year, it was not due to a lack of strategic or market synergy, or to regulator intrusion. According to a New York Times report, the deal failed “because of an insurmountable power struggle between the two companies’ chairmen…” (The New York Times, October 14, 1998, p. C1).

Breakdowns in human interaction and communication play a pivotal role in organizational life. In the case of Monsanto and American Home Products, the CEOs of the two companies had very different approaches to leadership. One spent his lunch hour playing basketball with employees. The other refused to move to the company’s new headquarters, preferring to stay in touch with key employees by email. The two leaders gradually began to question each other’s motives and moves. For instance, when one of the chairmen recommended a candidate for CFO, the other circulated a memo asserting that this man would never fill the role. Each felt that the other was undermining him and the company. They eventually proved unable to work together, and the merger fell through.

Sometimes apparently successful mergers also quickly show signs of strain. Eight months into their venture, Citigroup, the new amalgamation of Travelers Group and Citicorp, fired James Dimon, the man who acted as peacemaker between, and was assumed to be the heir apparent to, this firm’s two co-chief executives. Dimon was widely respected; his departure came not as a result of poor performance but, as one manager put it, “corporate politics.”

Executives interviewed later said that the collapsed Monsanto and American Home Products deal was “not in the best interests of the shareholders” and that Dimon’s surprising exit “was the best thing for the business.” Yet this kind of talk covers up more honest accounts about what happened. According to reports, the leaders in each of these situations hit awkward conflicts about a range of substantive issues: ultimate control in a “co-CEO” scenario, membership of important executive teams, and the timing of integrating disparate cultures and businesses. In the end, these people failed to find a way to talk and think together effectively to resolve these difficult issues.

Although we all may not be dealing with strained or failing multibillion dollar corporate mergers, we are probably quite familiar with such difficulties in communication and trust and the way these can dramatically affect organizational performance. So how do we create environments that can transform these difficulties into successes?

This article explores how “dialogic leadership,” an approach that has evolved from the core principles from the field of “dialogue,” can lead to the creation of environments that can dissolve fragmentation and bring out people’s collective wisdom.

The Concept of Dialogue

In the new knowledge-based, networked economy, the ability to talk and think together well is a vital source of competitive advantage and organizational effectiveness. This is because human beings create, refine, and share knowledge through conversation. In a world where technology has led to the erosion of traditional hierarchical boundaries, and where former competitors (such as Exxon and Mobil) contemplate becoming bedfellows, the glue that holds things together is no longer “telling” but “conversing.”

The term “dialogue” comes from Greek and signifies a “flow of meaning.” The essence of dialogue is an inquiry that surfaces ideas, perceptions, and understanding that people do not already have. This is not the norm: We typically try to come to important conversations well prepared. A hallmark for many of us is that there are “no surprises” in our meetings. Yet this is the antithesis of dialogue. You have a dialogue when you explore the uncertainties and questions that no one has answers to. In this way you begin to think together – not simply report out old thoughts. In dialogue people learn to use the energy of their differences to enhance their collective wisdom.

Dialogue can be contrasted with “discussion,” a word whose roots mean “to break apart.” Discussions are conversations where people hold onto and defend their differences. The hope is that the clash of opinion will illuminate productive pathways for action and insight. Yet in practice, discussion often devolves into rigid debate, where people view one another as positions to agree with or refute, not as partners in a vital, living relationship. Such exchanges represent a series of one-way streets, and the end results are often not what people wish for: polarized arguments where people withhold vital information and shut down creative options.

Although it may make logical sense to have dialogue in our repertoire, it can seem illusive and even a little quaint. Yet the fact remains that every significant strategic and organizational endeavor requires people at some stage to sit and talk together. In the end, nothing can substitute for this interpersonal contact. Unfortunately, much of our talk merely reinforces the problems we seek to resolve. What is needed is a new approach to conversation, one that can enable leaders to bring out people’s untapped wisdom and collective insights.

Human beings create, refine, and share knowledge through conversation.

“Dialogic leadership” is the term I have given to a way of leading that consistently uncovers, through conversation, the hidden creative potential in any situation. Four distinct qualities support this process: the abilities (1) to evoke people’s genuine voices, (2) to listen deeply, (3) to hold space for and respect as legitimate other people’s views, and (4) to broaden awareness and perspective. Put differently, a dialogic leader is balanced, and evokes balance, because he can embody all four of these qualities and can activate them in others.

An old story about Gandhi illustrates this concept well. A man came to Gandhi with his young son, complaining that he was eating too much sugar. The man asked for advice. Gandhi thought for a moment and then said, “Go away, and come back in three days.” The man did as he was asked and returned three days later. Now Gandhi said to the boy, “You must stop eating so much sugar.” The boy’s father, mystified, inquired, “Why did you need three days to say that?” Gandhi replied, “First, I had to stop eating sugar.” Similarly, dialogic leadership implies being a living example of what you speak about – that is, demonstrating these qualities in your daily life.

Four Action Capabilities for Dialogic Leaders

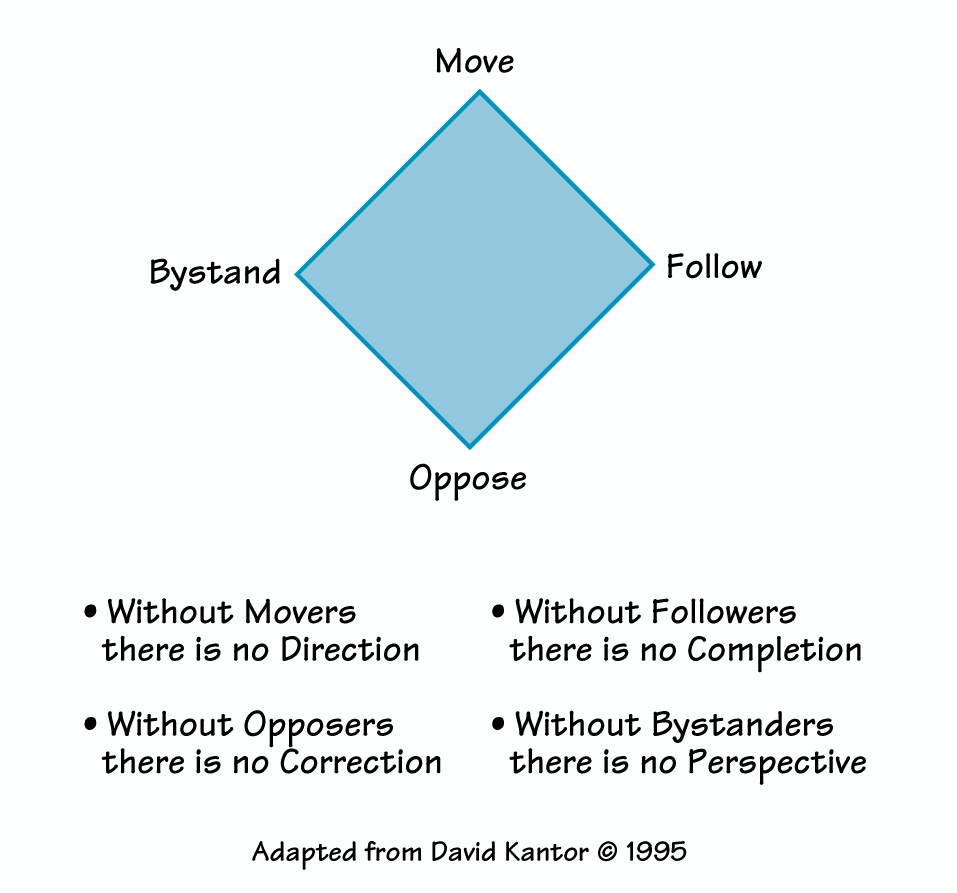

The four qualities for a dialogic leader mentioned above are mirrored in four distinct kinds of actions that a person may take in any conversation. These actions were identified by David Kantor, a well-known family systems therapist (see “Four-Player Model”). Kantor suggests that some people move – they initiate ideas and offer direction. Other people follow- they complete what is said, help others clarify their thoughts, and support what is happening. Still others oppose – they challenge what is being said and question its validity. And others bystand – they actively notice what is going on and provide perspective on what is happening.

FOUR PLAYER MODEL

Watching the actions people take can give you enormous information about the quality of their interactions and can indicate if they are moving in the direction of dialogue or discussion. For instance, in a dialogic system, any person may take any of the four actions at any time. Although people may have a preferred position, each individual is able to move and initiate, to follow and complete things, to oppose, and to observe and provide perspective. None of these roles is better or worse than the others. They are all necessary for the system to function properly. As people recognize these different roles and can act on this recognition, they begin to create a sequence of interactions that keeps the conversation moving toward balance.

In a system that is moving away from dialogue, people generally get stuck in one of the four positions. For instance, some people are “stuck movers”: They express one idea, and before that idea is established or acted upon, they give another, and another, making it difficult to know what to focus on. But perhaps most revealing of non-dialogic interactions are the ritualized and repetitive interactions that people fall into that systematically exclude one or more of the positions.

In the Monsanto merger process, for instance, the two CEOs became locked in a dynamic where one would initiate an action, and the other would oppose and neutralize it, leading the other to push back even harder. The conflict eventually escalated to the point where it sabotaged the deal.

An intense move-oppose cycle between two high-powered players like this one often prevents others from fulfilling their roles as “bystanders” and “followers.” The bystanders, who can see the ineffective exchange, often become “disabled,” imagining that no one wants them to identify what is happening. So the knowledge they carry is lost. At the same time, people who might otherwise be inclined to follow one side or the other to help complete what is being said tend to stay on the sidelines, for fear of getting caught in the cross-fire. The result is that the interaction remains unbalanced.

The quality and nature of the specific roles can often cause difficulties. For example, opposers are generally branded as troublemakers because they question the prevailing wisdom when people would prefer to have agreement. For this reason, others often tune them out. This failure to acknowledge the value of the opposer’s perspective leads them to raise their voices and sometimes increase the critical tone of their comments. In such cases, people hear the criticism, but not the underlying intent, which is almost always to clarify, correct, or bring balance and integrity to the situation.

A dialogic leader will often look for ways to restore balance in people’s interactions. For instance, she might strengthen the opposers if they are weak or reinforce the bystanders if they have information but have withheld it. Genuinely making room for someone who wants to challenge typically causes them to soften the stridency of their tone and makes it more possible for others to hear what they have to say. Reinforcing and standing with those who have delicate but vital information can enable them to reveal it. The simple rule here is: Pay attention to the actions that are missing and provide them yourself, or encourage others to do so.

Balancing Advocacy and Inquiry

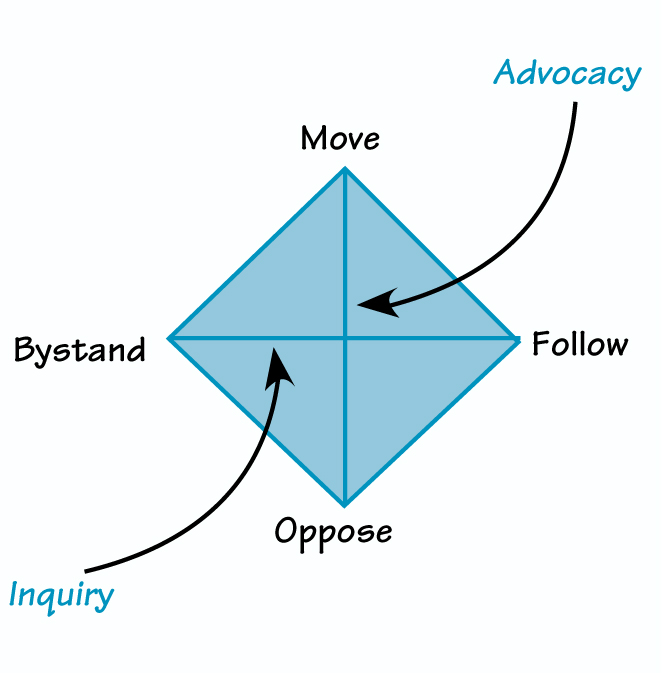

One central dimension in a dialogue is the emergence of a particular balance between the positions people advocate and their willingness to inquire into their own and other’s views. Professors Chris Argyris and Don Schön first proposed the concepts of “advocacy” and “inquiry” to foster conversations that promote learning (see their book Organizational Learning, Addison-Wesley, 1978 for a fuller explanation). In the vast majority of situations, advocacy rules: People are trained to express their views as fast as possible. As it is sometimes put, “People do not listen, they reload.” They attribute meaning and impute motives, often without inquiring into what others really meant or intended. This was evidently the case in the merger situations described above. Bellicose advocacy stifles inquiry and learning.

BALANCING ADVOCACY AND INQUIRY

The four-player model further reveals the relationship between advocacy and inquiry (see “Balancing Advocacy and Inquiry”). To advocate well, you must move and oppose well; to inquire, you must bystand and follow. Yet again, the absence of any of the elements hinders interaction. For instance, someone who opposes, but fails to also say what he wants (i.e., moves) is likely to be less effective as an advocate. Similarly, someone who follows what others say (“tell me more”) but never provides perspective may draw out more information but never deepen the inquiry. Thus, the figure “Balancing Advocacy and Inquiry” reveals another way to track the action in a conversation and offer balance into it.

Four Practices for Dialogic Leadership

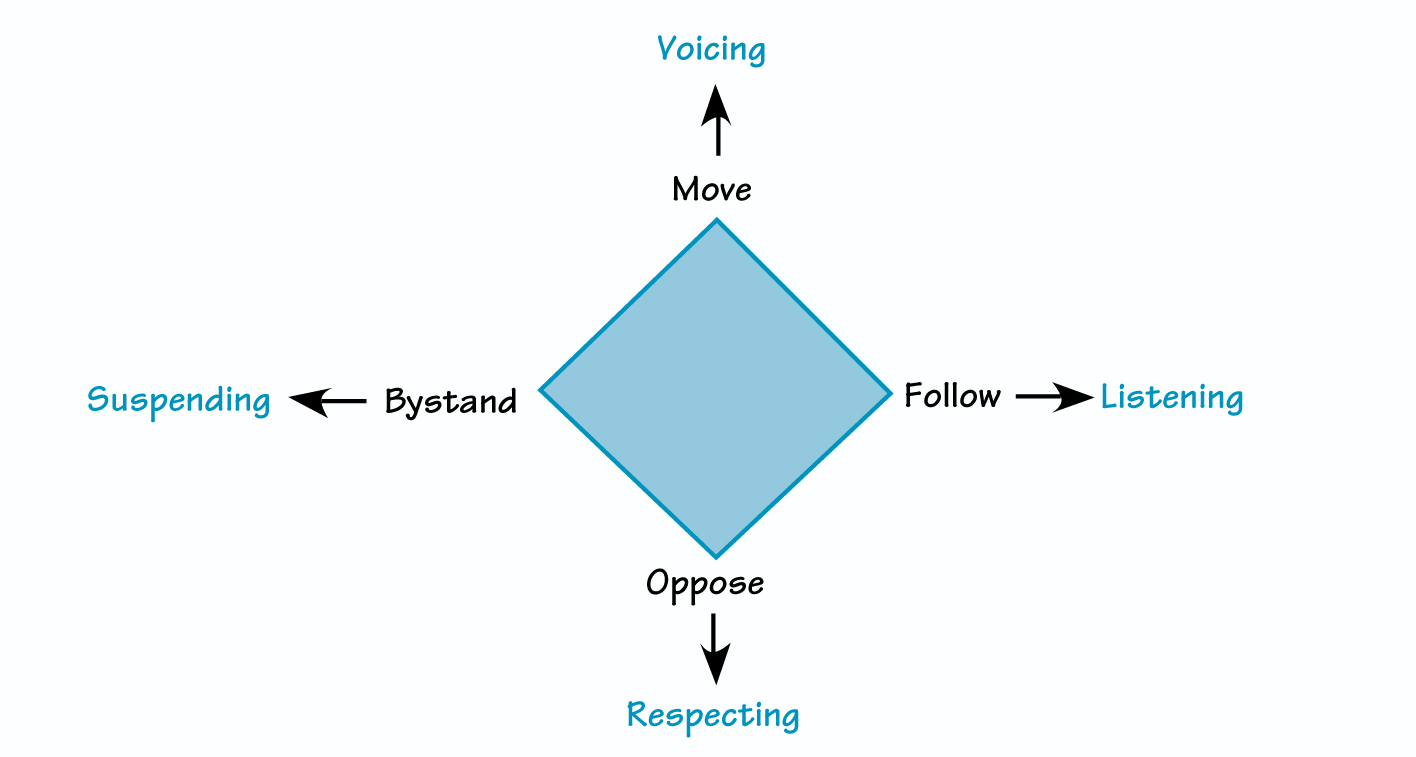

Balanced action, in the sense named here, is an essential and necessary precondition for dialogue. But it is not sufficient. Dialogue is a qualitatively different kind of exchange. Dialogic leaders have an ear for this difference in quality and are constantly seeking to produce it in themselves and others. I have found that there are four distinct practices that can enhance the quality of conversation. These four correspond well to the four positions named above.

For instance, you can choose to move in different ways: by expressing your true voice and encouraging others to do the same, or by imposing your views on others. You can oppose with a belief that you know better than everyone else, or from a stance of respect, in which you acknowledge that your colleagues have wisdom that you may not see. Similarly, you can follow by listening selectively, imposing your interpretation of what the speaker is presenting. Or you can listen as a compassionate participant, grounding your understanding of what is said in directly observable experience. Finally, you can bystand by taking the view that only you can see things as they are, or you can suspend your certainties and accept that others may see things that you miss. In order to make conscious choices about our behavior, we need to become aware of our own intentions and of the impact of our actions on others.

There are four practices implied here — speaking your true voice, and encouraging others to do the same; listening as a participant; respecting the coherence of others’ views; and suspending your certainties. Each requires deliberate cultivation and development (see “Four Practices for Dialogic Leadership”).

FOUR PRACTICES FOR DIALOGIC LEADERSHIP

Listening. Recently, a manager in a program I was leading said, “You know, I have always prepared myself to speak. But I have never prepared myself to listen.” This is because we take listening for granted, although it is actually very hard to do. Following well requires us to cultivate the capacity to listen – rather than simply impose meaning on what other people are saying. To follow deeply is to blend with someone to the point where we begin to participate fully in understanding how they understand. When we do not listen, all we have is our own interpretation.

Equally important is the ability to listen together. To listen together is to learn to be a part of a larger whole – the voice and meaning emerging not only from me, but from all of us. Dialogues often have a quality of shared emergence, where in speaking together, people realize that they have been thinking about the same things. They are struck when they begin to hear their own thoughts coming out of the mouths of others. Often decisions do not need to be made; the right next step simply becomes obvious to everyone. This kind of flow, while rare, is made possible when we relax our grip on what we think and listen for what others might be thinking. In this situation, we begin to follow not only one another, but the emerging flow of meaning itself.

Respecting. Respect is the practice that shifts the quality of our opposing. To respect is to see people, as Humberto Maturana puts it, as “legitimate others.” An atmosphere of respect encourages people to look for the sense in what others are saying and thinking. To respect is to listen for the coherence in their views, even when we find what they are saying unacceptable.

Peter Garrett, a colleague of mine, has run dialogues in maximum security prisons in England for four years. He deals with the most serious, violent offenders in that country on a weekly basis. Together, they have produced some remarkable results. For instance, prisoners who will not attend any other sessions come to the dialogue. Offenders who start off speaking incomprehensibly and who carry deep emotional wounds gradually learn to speak their voice and to listen. Peter carries an unusual ability to respect, which reassures and strengthens the genuineness in others. This stance enables him to challenge and oppose what they say, without evoking reaction. I asked him to share the most important lesson that he has learned in his work. He said, “Inquiry and violence cannot coexist.” True respect enables genuine inquiry.

Suspending. When we listen to someone speak, we face a critical choice. On the one hand, we can resist the speaker’s point of view. We can try to get the other person to understand and accept the “right” way to see things. We can look for evidence to support our view that they are mistaken and discount evidence that may point to flaws in our own logic. This behavior produces what one New York Times editorial writer called “serial monologues,” rather than dialogue.

On the other hand, we can learn to suspend our opinion and the certainty that lies behind it. Suspension means that we neither suppress what we think nor advocate it with unilateral conviction. Rather, we display our thinking in a way that lets us and others see and understand it. We simply acknowledge and observe our thoughts and feelings as they arise without feeling compelled to act on them. This practice can release a tremendous amount of creative energy. To suspend is to bystand with awareness, which makes it is possible for us to see what is happening more objectively.

For instance, in one of our dialogues with steelworkers and managers, a union leader said, “We need to suspend this word union. When you hear it you say ‘Ugh.’ When we hear it we say ‘Ah.’ Why is that?” This statement prompted an unprecedented level of reflection between managers and union people. Our research suggests that suspension is one of several practices essential to bringing about genuine dialogue.

Voicing. Finally, to speak our voice is perhaps one of the most challenging aspects of dialogic leadership. “Courageous speech,” says poet David Whyte in his book The Heart Aroused, “has always held us in awe.” It does so, he suggests, because it is so revealing of our inner lives. Speaking our voice has to do with revealing what is true for each of us, regardless of all the other influences that might be brought to bear on us.

In December 1997, around a crowded table in the Presidential Palace in Tatarstan, Russia, a group of senior Russian and Chechen officials and their guests were in the middle of dinner. Things had been tense earlier in the day. Chechnya had recently asserted its independence through guerrilla warfare and attacks on the Russians. They had shocked the world by forcing the Russian military to withdraw and accede to their demands for recognition as an independent state. The Chechens were deeply suspicious of the academics and Western politicians who had gathered everyone in that room; the Chechens feared that they were Russian pawns intent on derailing Chechen independence. The Russians, for their part, were fearful of adding further legitimacy to what they considered a deeply troubling situation.

And yet, despite all this suspicion, after a few hours people began to relax. At the first toast of the evening, the negotiator/facilitator of the session stood up and said, “Up until a few days ago, I had been with my mother in New Mexico in the States. She is dying of cancer. I debated whether to come here at all to participate in this gathering. But when I told her that I was coming to help facilitate a dialogue among all of you, in this important place on the earth, she ordered me to come. There was no debate. So here I am. I raise my glass to mothers.” There followed a long moment of silence in the room.

Dialogic leaders cultivate listening, suspending, respecting, and voicing

It is in courageous moments like these that one’s genuine voice is heard. Displays of such profound directness can lift us out of ourselves. They show us a broader horizon and put things in perspective. Such moments also remind us of our resilience and invite us to look harder for a way through whatever difficulties we are facing. When we “move” by speaking our authentic voice, we set up a new order of things, open new possibilities, and create.

Changing the Quality of Action

Dialogic leaders cultivate these four dimensions – listening, suspending, respecting, and voicing — within themselves and in the conversations they have with others. Doing so shifts the quality of interaction in noticeable ways and, in turn, transforms the results that people produce. Failing to do so narrows our view and blinds us to alternatives that might serve everyone.

For instance, in the Monsanto merger story, the CEOs did not seem to respect the coherence of each other’s views. Each one found the other more and more unacceptable. Although we do not know for sure, it seems likely that they did not reflect on perspectives different from their own in such a way that enabled them to see new possibilities. The paradox here is that suspending one’s views and making room for the possibility that the other person’s perspectives may have some validity could open a door that would be otherwise shut. By becoming locked into a rigid set of actions, these leaders ruled out a qualitatively different approach — one that they could have made if they had applied the four dialogic practices described above.

Dialogic leadership focuses attention on two levels at once: the nature of the actions people take during an interaction and the quality of those interactions. Kantor’s model is a potent aid in helping diagnose the lack of balance in actions in any conversation. By noticing which perspective is missing, you can begin to reflect on why this is so and quickly gain valuable information about the situation as a whole.

Dialogic leadership can appear anywhere, at any level of an organization. As people apply the principles outlined above, they are learning to think together, and so greatly increase the odds that they will build the expansive relationships required to build success in the new economy.

William N. Isaacs is the president of Dialogos, a Cambridge, Massachusetts-based consulting firm, and is a lecturer at MIT’s Sloan School of Management. This article is drawn from his new book, Dialogue and the Art of Thinking Together, to be published in May 1999 by Doubleday.