The next time you are involved in a seemingly unbreakable impasse, think about the dilemma faced by South Africans in the early 1990s. After centuries of violent and repressive white minority rule, the country began the long, painful transition to a racially egalitarian democracy led by the black majority. The situation was rife with danger, and yet opposition leaders and governmental officials—who came from dramatically contrasting worlds within the same society—found a way to overcome their tragic history to create a new South Africa.

How did the country’s citizens manage to solve this almost impossibly complex problem? And what lessons can the rest of us learn from this brave process and others like it around the world? According to Adam Kahane in Solving Tough Problems: An Open Way of Talking, Listening, and Creating New Realities (Berrett-Koehler, 2004), the key to forging a better future in our personal lives, organizations, and world is talking and listening openly.

An Alternative to Force

Although this approach may sound simplistic or naïve, Kahane has stories from some of the world’s most charged conflicts to show that it is neither. In Guatemala, home to a brutal civil war that left more than 200,000 people dead, representatives from all facets began to mend the tattered social fabric through devastatingly honest yet respectful conversation. In Argentina, a country that has been buffeted by economic woes and social chaos, leaders from the legal system engaged in a series of frank dialogue sessions that opened the door to judicial reform. And in South Africa, rather than remaining entrenched in fear or resorting to violence, white and black, right-wing and left-wing, jailers and jailed joined together to listen and be heard in the service of national reconciliation.

People typically approach complex problems either by maintaining the status quo or by trying to force a solution on others.

This approach to tough challenges is unusual, because it involves lowering defenses at a time when participants are most inclined to raise them. It requires openness in settings that have thrived on secrecy and silence. And it demands mutual trust from victims as well as from perpetrators.

But the reality is that, in every setting—international, community, organizational, family—people typically approach complex problems either by maintaining the status quo (that is, by doing nothing) or by trying to force a solution on others. In the latter case, those with more power generally prevail, at least in the short run. Kahane says, “Families replay the same argument over and over, or a parent lays down the law. Organizations keep returning to a familiar crisis, or a boss declares a new strategy. Communities split over a controversial issue, or a politician dictates the answer. Countries negotiate to a stalemate, or they go to war.”

Using force is problematic, in that it leaves behind a swath of physical and psychic damage, perpetuates fear, and sows the seeds of rebellion. Rather than drawing people together, it drives them apart. In imposing their will, those in power shut down all other approaches, options, and possibilities, relying solely on their own judgment.

Kahane points out that this approach might work for straightforward issues, but it is woefully inadequate for dealing with today’s intricate problems. He defines these as situations that are:

Dynamically complex—Causes and their effects are separated by space and time, making the links between them difficult for any one person or group to identify.

Generatively complex—They are unpredictable and unfold in unfamiliar ways.

Socially complex—The people involved are extremely diverse and have very different perspectives.

Based on this definition, solving tough problems requires input from a wide range of stakeholders. Without the open and honest involvement of people from throughout the system, any resolution will be at best short-lived and at worst brutal.

Beyond the Comfort Zone

What kind of magic lies in talking and listening? After all, we talk continually, even when we’re disagreeing. Kahane shows that the quality of our interactions can make a major difference in the outcomes we achieve. Most of the time, when we talk, we’re asserting one point of view—our own—as being the truth. And when we listen, it’s generally to ourselves, as we prepare to refute something someone else has said.

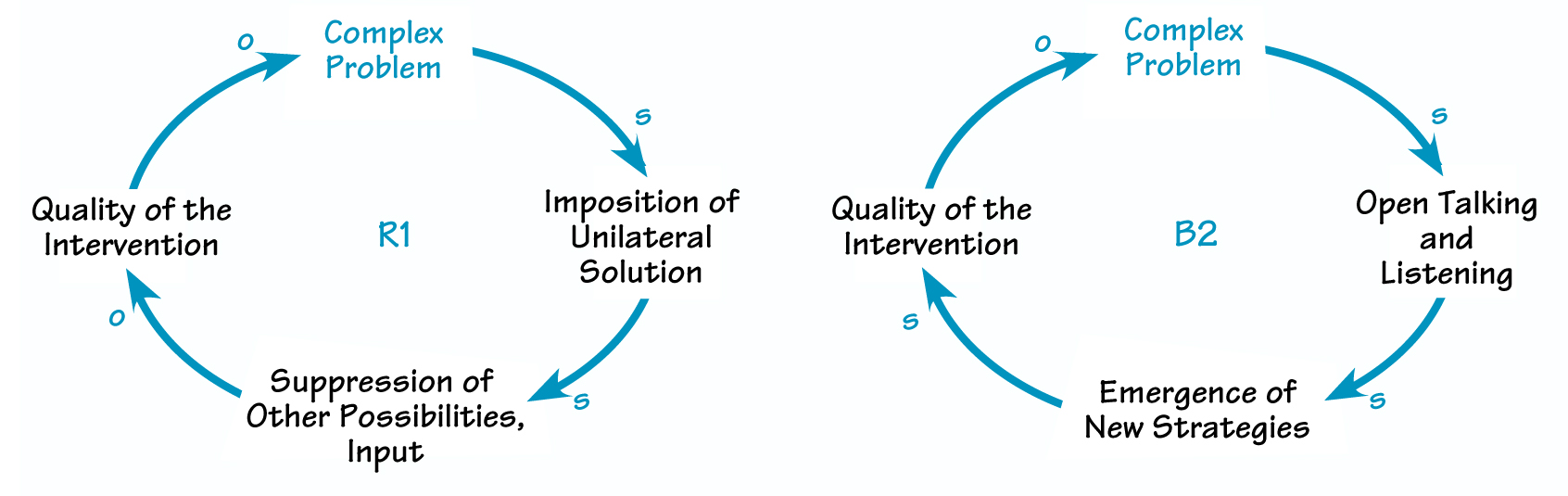

TWO APPROACHES TO COMPLEX PROBLEMS

People typically approach complex problems either by doing nothing or by imposing a solution (R1). But without input from others, the quality of the intervention is generally poor, and the problem reappears. With each turn of the cycle, the severity of the problem grows, and the evel of force required to implement a solution rises. A more sustainable approach is for stakeholders to talk and listen openly, which can lead to the emergence of new strategies and high-quality actions (B2).

To avoid becoming mired in conflict, we need to transcend our typical modes of talking and listening (see “Two Approaches to Complex Problems”). Based on his experiences, Kahane observes, “When someone speaks personally, passionately, and from the heart, the conversation deepens. When a team develops a habit of speaking openly, then the problem they are working on begins to shift.” But he adds, “Often this is extremely difficult. People hesitate to say what they are thinking for many reasons, not only extraordinary but also ordinary: fear of being killed or jailed or fired, or fear of being disliked or considered impolite or stupid or not being a team player.” Nevertheless, if we want to create a new reality, we need to find the courage to speak up.

Listening in new ways means stretching beyond our comfort zone and being willing to be influenced and changed by others. It entails noticing and questioning our thinking and letting go of our attachment to our own ideas. Finally, open listening requires empathy and a genuine interest in other people, their experiences, and their perspectives. As Kahane quotes a South African bishop as saying, “We must listen to the sacred within each of us.”

Our Role in the Problem and Solution

But talking and listening aren’t enough—to create something new rather than merely re-create the past, we need to be able to translate novel forms of conversation into innovative modes of action. Central to this process is being able to see ourselves as part of both the problem and the emerging solution.

To illustrate this point, Kahane describes what happened during a series of workshops that he facilitated in South Africa, known as the Mont Fleur scenario project:, “A small group of leaders, representing a cross-section of a society that the whole world considered irretrievably stuck, had sat down together to talk broadly and profoundly about what was going on and what should be done. More than that, they had not talked about what other people—some faceless authorities or decision makers—should do to advance some parochial agenda, but what they and their colleagues and their fellow citizens had to do in order to create a better future for everybody.” They recognized that, just as they and their fellow citizens and their forebears had created the past, their collective actions would shape the nation’s future. That awareness opened up the possibilities for people to address the problems at a fundamental level.

For most of us, the consequences of continuing to rely on old ways of talking and listening are less dire than for the people whose stories are recounted in this book. But over the long run, we all face extraordinary challenges, including global climate change, the disparity between the wealthy and the poor, growing political instability around the world, and falling resource levels, among other growing crises.

These kinds of complex problems require people of courage to join together and forge peaceful, sustainable solutions. As Kahane concludes, “Every one of us gets to choose, in every encounter every day, which world we will contribute to bringing into reality. When we choose the closed way, we participate in creating a world filled with force and fear. When we choose an open way, we participate in creating another, better world.”

Janice Molloy is content director at Pegasus Communications and managing editor of The Systems Thinker.

Resources by Adam Kahane

Adam Kahane was a keynote speaker at the 2003 Pegasus Conference. His presentation, titled “The Potential of Talking and the Challenge of Listening,” is available in various formats:

Video DVD Order #D0301 Videotape Order #V0301 CD Audio Order #T0301C Audiotape Order #T0301

To view excerpts, go to www.pegasuscom.com/m2/media.html, scroll through the Video Gallery until you find Adam Kahane, and click on “Play.