The Milwaukee Area Technical College (MATC) is the largest two-year technical college in the U.S., serving nearly 70,000 students with an annual budget of over $203 million. Founded in 1912, the college was originally modeled after German trade schools, with an emphasis on factory-style efficiency. In addition, many of the college’s senior administrators in the 1940s and 1950s had served as officers in World War II, giving the college a long history of military-style leader-ship and a command-and-control culture.

In 1982, however, a period of massive change began. The president of the college was forced to resign, and the college subsequently went through four presidents over a span of 13 years. After the most recent departure, an interim CEO was brought in to “clean up the mess” while the board of directors searched for yet another replacement.

Although the interim president was considered highly competent, he had a reputation for being more like Atilla the Hun than Stephen Covey in terms of his leadership style. And despite the board’s assurances that any interim replacement would not be eligible for the position, the acting president was eventually hired permanently. This decision, on top of years of change and instability, sent the organization into a state of shock. Daily rumors circulated about potential firings, and few people in the college felt secure enough to take risks. In order to regain our effectiveness as an organization, we needed to somehow work on rebuilding our community. But first, we needed to address the underlying issues that had bred a culture of fear and mistrust.

Examining the Culture

In September 1994, I discovered an article in The Systems Thinker by Greg Zlevor entitled “Creating a New Work-place.” The article asserted that all organizations operate at some point along a “community continuum”: somewhere between “disciety” (dysfunctional society) and “community.” It seemed to me that in order to improve our organizational climate, we first needed to identify where we were on the continuum.

I shared the article with the director of research at MATC, and together we decided to conduct a “quick-and-dirty” survey based on Zlevor’s model to get a sense of how our colleagues viewed our organization (see “MATC Community Survey”). Once it was complete, we mailed the survey to the entire management council of the college (over 125 people).

To our surprise, we were inundated with phone calls the next morning. Many of the callers were struck by the candor of the statements, which were considered “undiscussables” in the organization. (The statements were taken verbatim from Zlevor’s description of the different positions on the continuum.) Some callers had questions about confidentiality (their names were inadvertently included on the back of the survey, due to the internal mail routing labels). Several callers wanted to know if the new president was behind the survey. Still others were relieved that our organization was beginning to talk about these issues:

Amazingly, we received more than an 85% return rate on the surveys. We separated the responses into five piles, each representing a point along Zlevor’s continuum. The results were almost perfectly bimodal: people either saw the college as dysfunctional (“This place is so political”) or formative (“We have our ups and downs, but mostly ups”). We surmised that because there was no shared sense of the community as a whole, people’s experience of the college depended to a large extent on the ups and downs of their daily experience.

MATC Community Survey

- This is war. Every person is for him or herself.

- This place is so political. I see glimpses of kindness, but I usually feel beat up. I must protect myself.

- I do my part; they do theirs. As long as I keep to myself and do my job, I’m okay. People cooperate. We have our ups and downs, but mostly ups. There’s a fair amount of mist. I can usually say what is on my mind.

- I can be myself. I feel safe. Everyone is important. Our differences make us better. We bring out the best in each other.

We brought our data to the next meeting of the senior administrators (all of whom had been recipients of the survey) in order to explore the results. The dynamics of the ensuing discussion were as revealing as the survey results had been. Some people immediately demanded to know, “Why was my name put on the back of the survey?” Others became defensive, wondering, “Why wasn’t I told about the original article?” The group as a whole seemed to attack the validity of the survey itself, asking, “Why was this even done?” Their reactions seemed to reflect the overall climate of the organization—one of fear, mistrust, and well-entrenched defensive routines. At the conclusion of the meeting, they recommended that the entire survey episode be put to rest. However, it was not going to be forgotten that easily.

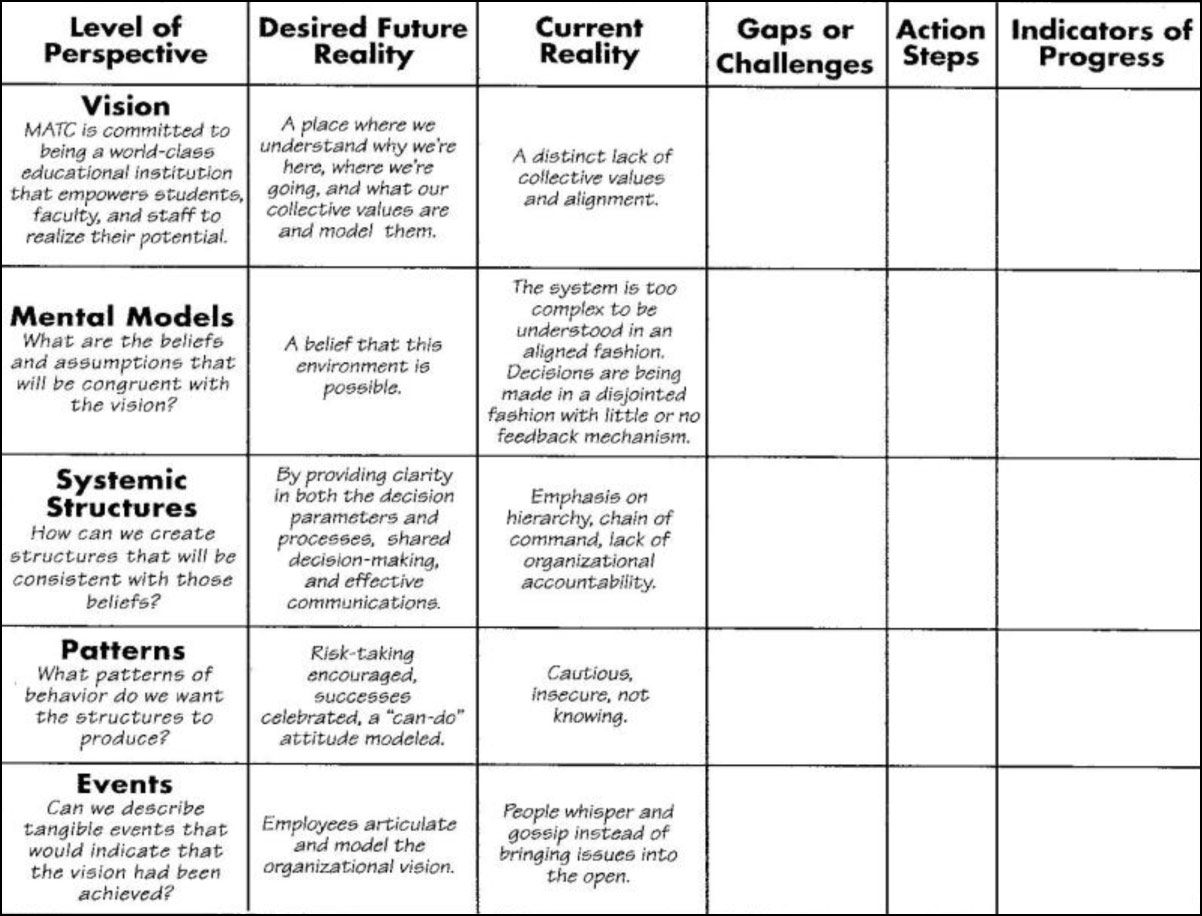

MATC Vision Deployment Matrix

To get a better picture of current reality at the college, and to paint a picture of the desired future. the STOL group used a tool called the Vision Deployment Matrix!”. This diagram shows the collective responses of the STOL group to the first two columns of the matrix.

Reframing the Work

Earlier that year, a small group of people representing a cross-section of management began meeting regularly to learn more about systems thinking concepts and tools. The official title for the group was STOL—for Systems Thinking and Organizational Learning—but we jokingly referred to our get-togethers as “Systems Thinking over Lunch.” Since our group had been using different case studies to hone our skills, I brought up the survey as a good opportunity to explore the larger dynamics at play in the organization. However, we quickly realized that the implications of this project were larger than any of our previous case studies—it really involved reframing how we thought about the nature of our entire organization.

As one of the ways to provide a framework for this effort, we decided to use the Vision Deployment Matrix TM, a tool developed by Daniel Kim for helping groups articulate an action plan for moving from current reality toward a shared vision (see “Vision Deployment Matrix T”: A Framework for Large-Scale Change,” February 1995). The nine members of our STOL group filled out the Vision Deployment Matrix individually, then worked together to weave the individual perspectives into a collective matrix (see “MATC Vision Deployment Matrix”). After we filled out the first two vertical columns of the matrix—”Desired Future Reality” and “Current Reality”—we decided to get the president’s input to see how his perceptions compared to our own.

After hearing a short explanation of the matrix, the president also filled out the first two columns. Interestingly, his responses were similar to ours. For example, in the box that indicated the systemic structures needed to achieve the vision, the STOL group had noted a need for “shared decision-making” and “effective communications,” while the president expressed a desire for “more constructive meetings.” This gave the STOL group confidence that the president shared our understanding of the vision and current reality of the college. In addition, his willingness to participate sent an important signal that he supported our efforts to examine and improve our organizational culture.

Improving Communication

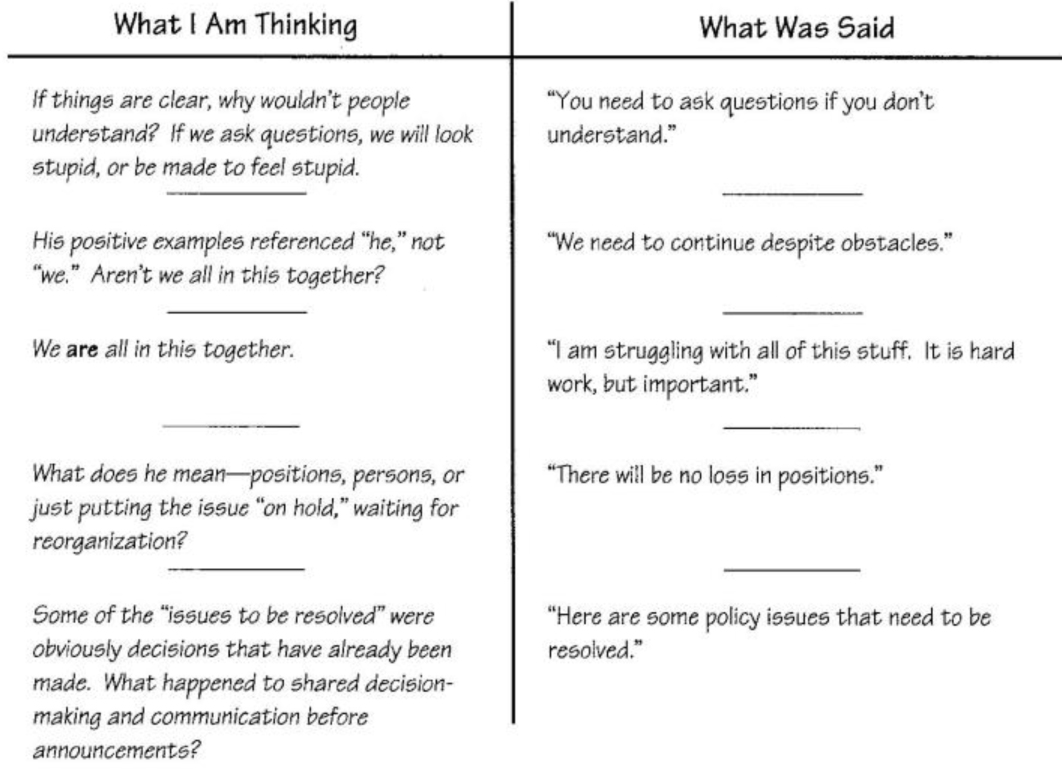

Through the process of developing our matrix, we began to realize that one of our biggest obstacles to achieving our vision of improved community was the unspoken mental models held by members of the college—the untested assumptions that were preventing open and effective communication. This became clear at the next meeting of the Management Council, when the president gave a presentation on the issues facing the organization. After his talk, the STOL group then conducted a “left-hand column” exercise, in which the participants wrote down on the right side of the page what the president said, and on the left side they voiced what they thought or felt in reaction to his comments.

What the group discovered through the process was that we all tend to hear what we expect to hear. For example, the people who anticipated hearing only “bad news” heard precisely that. Those who expected to see a “tough guy” in the president had their predictions confirmed. And, intriguingly, the people who were open to organizational change saw the shifts that were occurring as a positive development for the college (see “Left-Hand Column: One Perspective” for an example of this exercise). This exercise opened up our awareness of the significant role our mental models play in selecting what we hear and don’t hear, and it had the desired effect of opening the group up to a deeper level of conversation. Our work in developing a deeper level of community was beginning to take hold.

Preliminary Results

When the STOL group developed its Vision Deployment Matrix, we noted that one of the indicators of progress toward developing community would be an openness in communication throughout the administration of the college, as well as an increased ability as a group to suspend our assumptions and inquire more deeply into each other’s reasoning. The area where we have seen the greatest progress toward this goal has been in the Management Council meetings. In the past, they were full-day sessions that consisted primarily of lectures given by the president and/or his direct reports. The attendees often felt “talked at” for hours on end. There was very little participation, and many attendees passed the time by surreptitiously doing paperwork. When we did a quick analysis of the cost of the meetings, we discovered that the college was spending approximately $100,000 per year on a function that yielded very little benefit.

We decided, therefore, to use the Management Council meetings as an opportunity to work on developing better communication, and to begin to tap into the collective intelligence of the members. We shortened the meetings to half-day sessions, eliminated the speakers, and refocused the agenda on working together in small groups to tackle some of the serious issues facing our institution. At the first of the redesigned management meetings, two college-wide issues that were generally considered to be undiscussables were addressed: (1) how to better implement the entire CQI process; and (2) how to productively examine the positive and negative effects of the changes that occurred within the organization during the last several years.

In order to facilitate more productive communication at the meeting, we assigned people to small groups, each of which represented a cross-section of the college. As the groups were invited to share their insights with the entire council, previously undiscussable issues were sufficed, and some very productive conversations ensued. For example, the “undiscussable” issue of a compensation and benefits inequity between union and non-union employees was raised, and specific recommendations were made for further action. After the meeting, we shared the outputs with the president (who chose not to be present during the meeting so as not to inhibit open communication), and we forwarded the results to the CQI Steering Committee of the college.

Left-Hand Column: One Perspective

After a talk by the president to the Management Council the STOL group conducted a left-hand column” exercise. In order to surface the mental models operating in the group.

Our Ongoing Work

The evaluations from our first redesigned Management Council meeting were very positive. Many people commented that the college was “finally moving forward.” But even as we are celebrating this modest success, we recognize that we have a long way to go toward our goal of developing a healthy community at MATC. In order to continue our work on organizational integration and community building, the STOL group has identified four areas for further action:

- continue to work on building communication and trust

- make systems thinking courses and materials available to others at the college

- continue to develop systemic solutions for problems at the college, working with the president to effect high-leverage changes

- re-survey the Management Council to accurately assess current reality at the college

As we develop our skills in community building and in creating structures that will sustain that community, we believe we can make a profound difference in the organizational culture. With the help of organizational learning tools, we are confident that our culture will continue to move toward openness and community.

James B. Rieley directs the Center for Continuous Quality improvement at Milwaukee Area Technical College. He also consults with business and industry, government, and educational institutions. Editorial support for this article was provided by Diane J. Reed and Colleen P. Lannon.

This story was presented at the 1995 Systems Thinking in Action”‘ Conference.