Vision can be a powerful force for action when it is clearly articulated and there is a genuine desire to bring it into reality. Yet many visioning efforts fail to bring about the desired results. Many organizations that catch the vision “fever” believe the job is finished once a small group of top managers produce a vision statement and announce it to the rest of the organization. Expecting that the vision statement in and of itself will produce transformation, the initial group often disregards the importance of the process that brought about the commitment. When misinterpreted in this way, vision becomes a thing that people are expected to buy into, rather than a lively process of sharing what we most care about in a way that creates enthusiasm and shared commitment.

“People Resist Change”

When efforts to roll out a vision statement are met with resistance or produce no tangible results, we often conclude that “people resist change.” In many organizations, this has become a corporate maxim that is often accepted without challenge. As organizations undertake change efforts — whether visioning, TQM, reengineering, or something else — much discussion and effort is usually devoted to dealing with people who are resistant to change. How do we convince them to go along with the plan? What incentives can we use to entice them to buy in?

Rather than spending time formulating strategies to deal with these “unchangeable” people, we should step back and ask ourselves, “Do they really exist?” When invited to participate in creating something they truly care about, people are usually more than willing to change — and sometimes they are even impatient with the larger organization’s inability to move fast enough toward the goal. Most people do not resist change; they resist being changed when it is imposed from the outside.

The Chasm

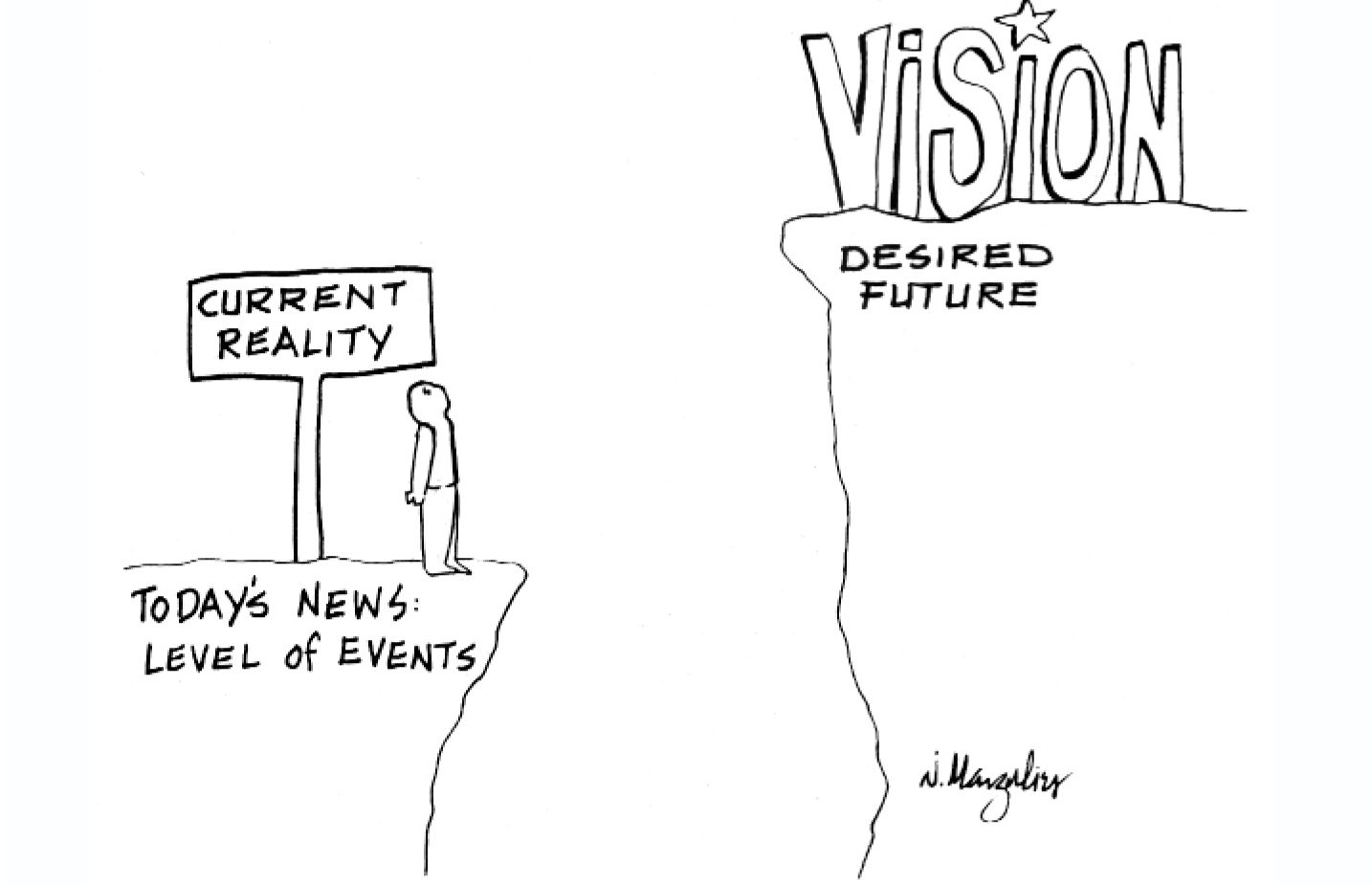

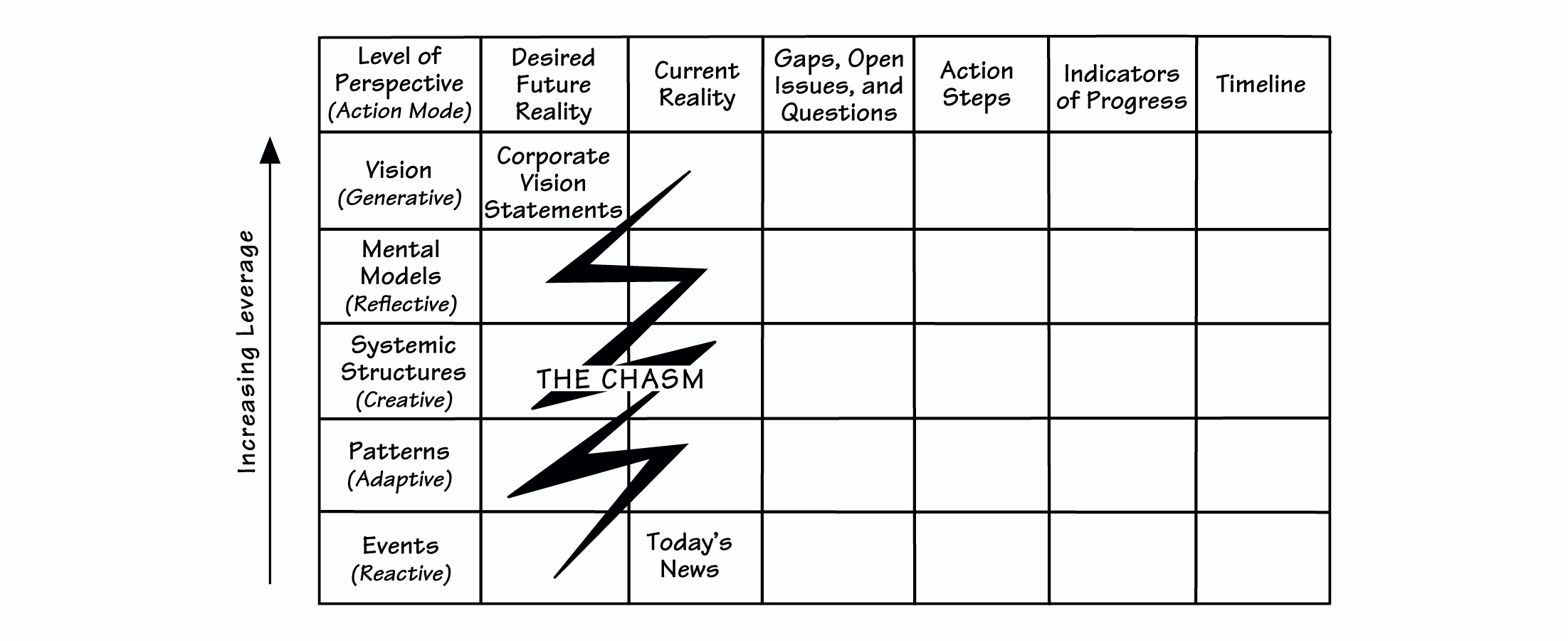

Designing a process for involving people in sharing a vision is only one part of the formula for success. Visioning also requires a commitment to articulating current reality with clarity and honesty — talking about daily events as they really are, not as we wish them to be. In between vision and current reality lies an enormous “chasm” that must be crossed in order to realize the desired future.

Many change efforts fail to achieve expected results because they do not strategically address ways to bridge the “chasm.” Successfully managing large-scale organizational change requires a comprehensive, broad-based approach. To bridge the gap between future and current reality, we need to be explicit about the multiple levels on which we must think and act: events, patterns of behavior, systemic structure, mental models, and vision.

Vision Deployment Matrix™

The Vision Deployment Matrix offers a schema for strategically planning how to cross the “chasm” between current reality and vision by painting a comprehensive picture of the desired future reality and current reality at five levels of perspective (see “Vision Deployment Matrix™”). The Vision Deployment Matrix is meant to help everyone in the organization understand the current reality, the desired future reality, the gaps between the two, and the actions that should be taken to close the gap. This includes translating the ideals of a vision into a practical reality that guides and affects not only the strategic thinking in the organization, but the day-to-day operations as well.

To see how the Vision Deployment Matrix can be used to plan a large-scale change process, let’s look at the health-care industry, and “fill in” the matrix as we create a possible action plan for achieving a new vision of healthcare.

VISION DEPLOYMENT MATRIX ™

The Vision Deployment Matrix offers a schema for strategically planning how to cross the “chasm” between current reality and vision by painting a comprehensive picture of the desired future reality and current reality at each level of perspective.

Start at the Vision level of Desired Future Reality. Beginning with the desired future reality is desirable because it allows us to be expansive in our thinking and not get bogged down by current reality. It also frames the effort in terms of creating “what we want” rather than eliminating “what we don’t want.”

In the healthcare industry, for example, one vision of the future that has been articulated is “the creation of healthier communities.”

Move down the multiple levels of Desired Future Reality. Staying with our focus on the desired future reality, we can flesh out what the vision means at each level by asking the following questions:

Mental Models: “What are the beliefs and assumptions that will be congruent with the vision?”

Systemic Structures: “How can we create structures that will be consistent with those beliefs?”

Patterns of Behavior: “What patterns of behavior do we want the structures to produce?”

Events: “Can we describe tangible events that would indicate that the vision had been achieved?”

By addressing these kinds of questions, we can clarify how our desired future reality will operate at multiple levels and create a more robust picture of what we want.

In our healthcare example, the mental models we might have are that we are responsible for our own health, the human body needs to be approached holistically, and prevention is the highest leverage point. Systemic structures that are consistent with those beliefs might be smaller, more individualized service providers, self-help prevention programs, and networked information systems that contain fully integrated health profiles for each person. The patterns we might hope to see are a steady decrease in preventable diseases and less reliance on symptomatic treatments. At the level of events, we would envision patients interacting with doctors in two-way conversations that are mutually respectful of each other’s role and responsibility for the patient’s health.

Begin describing Current Reality at the level of Events. When we move to describing current reality, we want to start at the level of events because it is usually fairly easy to rattle off “today’s news” that characterizes the current system. We can then move up through the other levels.

In healthcare, the current system can be described as one where patients sit passively while the expert “treats” them. People are bounced from one physician to the next as each specialist tries to diagnose a singular or localized cause for an ailment. These events are characterized by a pattern of behavior that has shifted the burden of wellness from the patient to the medical expert. The predominant structures that support and produce these behaviors are the doctor-patient relationships, the narrow specialties, large hospitals that treat symptoms instead of people, and a system that has no direct feedback connection between the customer, the supplier, and the payer. These structures are the manifestations of a worldview that sees the human body as a collection of parts that are to be treated when they “break down.”

Articulate the operating (tacit) Vision in Current Reality. Although there may never have been an explicit vision, there is usually a tacit vision that is guiding the current reality. That is, when we look at the mental models, structures, patterns, and events, it appears as if they are being guided by an implicit vision of the way things ought to be. In healthcare, for example, the industry acts as if guided by a vision of being a disease treatment system, where the emphasis is on efficient diagnosis and treatment of health breakdowns.

Identify Gaps or Challenges at each level. After filling in each cell under Desired Future Reality and Current Reality, we want to highlight the gaps or challenges that surface at each level.

Formulate Action Steps to close the Gaps. For each of the gaps identified, formulate the actions that will begin addressing them at each level.

In between vision and current reality lies an enormous “chasm” that must be crossed in order to realize the desired future.

Establish Indicators of Progress. In any change effort, we need ways to measure our progress. We want to be able to answer the question, “How do we know when we have arrived?” It may also be helpful to establish appropriate time frames in which to expect progress at each of the levels.

Continual and Iterative Process. Although the steps outlined above have been presented in a linear fashion, the vision deployment process is a continual and iterative process. The emphasis should not be so much on whether we have the matrix filled in “just right,” but rather on the diligence with which we are focusing our efforts to continually clarify what goes in every part of the matrix.

Where Is the Leverage?

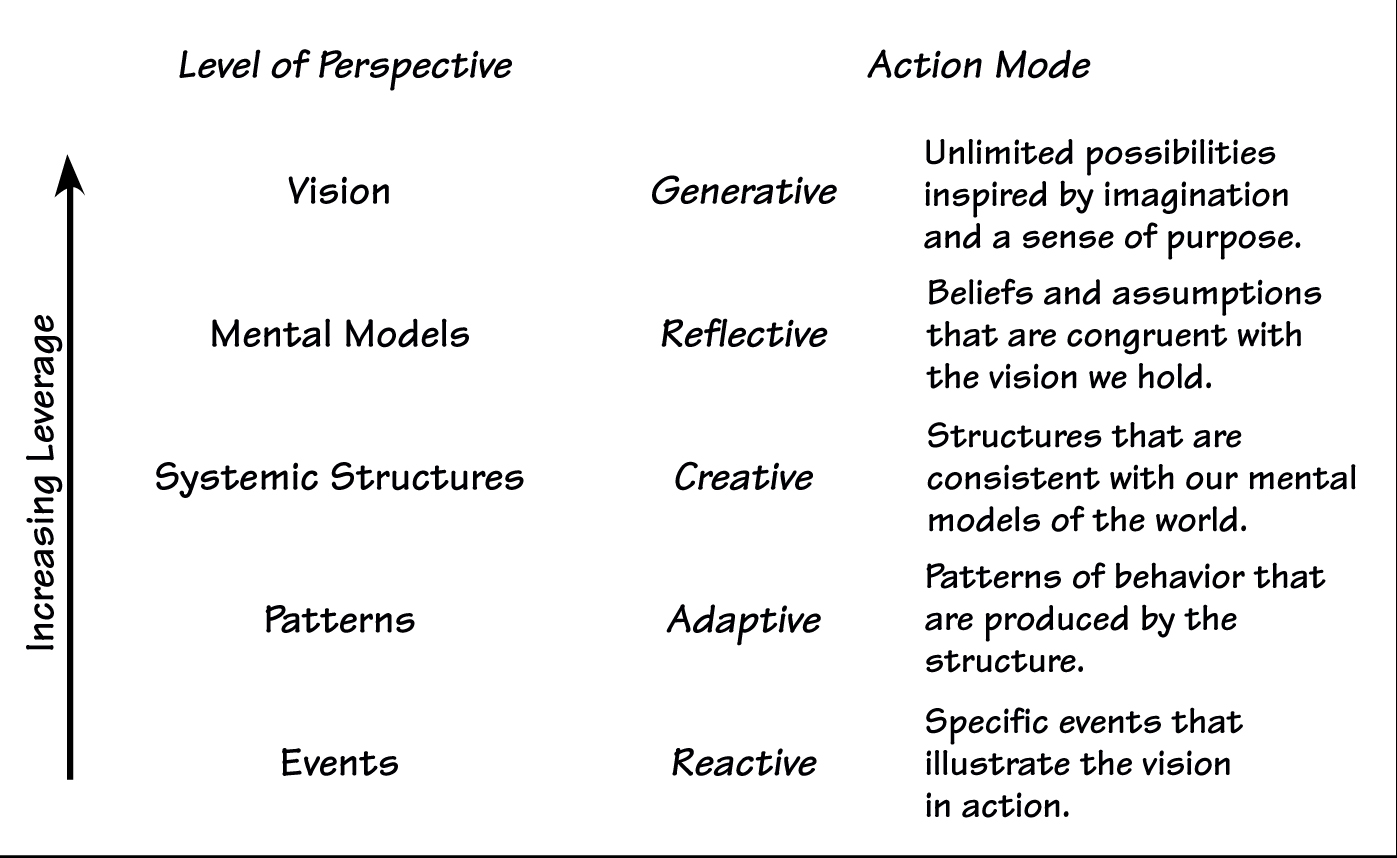

Our ability to influence the future increases as we move from the level of events to vision. This does not, however, mean that high-leverage actions can only be found at the higher levels. Leverage is a relative concept, not an absolute. When someone is bleeding, the highest leverage action at that moment is to stop the bleeding, not to formulate a vision of that person being completely healed. As we shift from looking at events to looking at shared vision, however, the focus moves from being present-oriented to being future-oriented. Consequently, the actions we take at the higher levels have more impact on future outcomes than on present events. (See “Summary of Action Modes” on p. 4, for an explanation of the types of actions that are characteristic of each level.)

In addition, our understanding of a situation at one level can feed back and inform our awareness at another level. Events and patterns of events, for example, can cause us to change systemic structures and also challenge our vision. The key to successful large-scale change is to operate at all levels simultaneously as much as possible.

The Implementation Challenge: From Vision to Reality

Articulating a compelling vision and building commitment around it marks the beginning of the journey, not the end. The greater challenge that lies ahead is to actualize the vision in every aspect of organizational life. There needs to be a clear and coherent strategy for making the vision a reality at multiple levels of the organization, including all divisions, departments, and teams. The bottom line is that in order for this work to be effective, it must be done by individuals at each level of the organization.

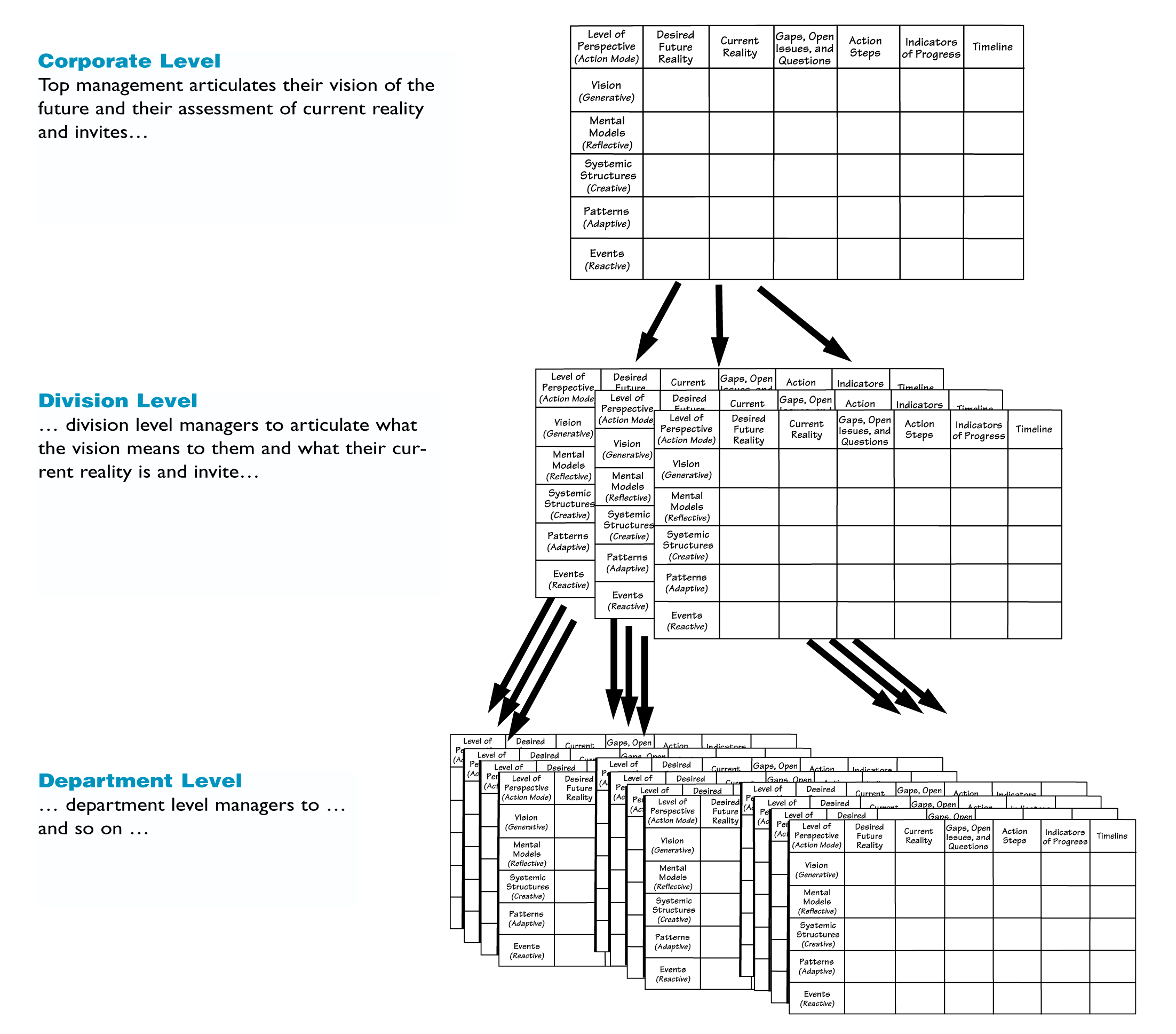

Top management may begin the deployment process by using the Vision Deployment Matrix to articulate a vision for the organization, but they also need to take the next step and invite those at the operating divisions to articulate what the vision means to them. Those managers, in turn, must invite those at the departmental level to articulate what the vision means to them, and so on (see “Organizational Deployment: An Action Plan” on p. 5).

Ultimately, visions must be real and meaningful to all those involved in order for them to be compelling and successful in transforming an organization. Although the vision deployment process may appear intensive and arduous, it is the shortest path to building an enduring shared vision. As many failed attempts at mandating visions from the top have shown, there are no short-cuts to building true shared vision. Simply put, no one can demand commitment from someone else. It is a personal choice that, once made, can be a powerful catalyst for change.

Daniel H. Kim, publisher of The Systems Thinker, is co-founder of the MIT Organizational Learning Center, where he is currently Learning Lab Research Project Director.

SUMMARY OF ACTION MODES

Events. Operating at the level of events means that whenever we encounter a defective part, we sort it out and either rework it or put it on the scrap pile. We may try to correct the situation by adjusting the machinery or by inspecting more closely, but our primary mode of action is reactive.

Patterns. If we look at events (scrap rates) over a period of time, we may notice a pattern, such as higher scrap rates at certain times of the day or higher variability on some machines. We can then adapt our processes to improve the current system.

Systemic Structures. The structure of our systems is what produces the patterns and events that create our day-to-day reality. It is also where mental models and vision are translated into action. When a system is in statistical control, it means that improvement can only come about by changing the system. By working at the systemic structure level, we can create new events and patterns by altering the system, rather than just adjusting or reacting to it.

Mental Models. Where do the systemic structures come from? They are usually a product of our ”mental models” — our internal pictures of how the world works. Operating at the level of mental models means understanding what our assumptions are, reflecting on them to test their relevancy, and changing them if necessary. Changing our systemic structures often requires a change in our mental images of what those structures can or ought to be.

If we can only conceive of manufacturing as one massive assembly operation, for example, then we will not be able to consider alternatives such as smaller independent manufacturing cells that can produce a higher mix of different products at lower volumes.

Vision. Surfacing, reflecting on, and changing our mental models is often a difficult and painful process. Why would we choose to go through such a process? Because we have a compelling vision of a new and different world that we are committed to creating. At the level of vision, our actions can be generative, bringing something into being that did not exist before. For example, a vision of providing the most options for the customer or a higher quality of work life for employees may create the impetus to reexamine old mental models of what a manufacturing plant “should” be.

ORGANIZATIONAL DEPLOYMENT: AN ACTION PLAN